One hundred years ago, Havana was a fast-growing metropolis that had outstripped the confinements of its old colonial walls. With plush new neighborhoods sprouting up haphazardly in the south and west, the city brimmed with life, creativity, and abundant sugar money, but it lacked an urban development plan. Enter Jean Claude Forestier, a French landscape architect who first arrived in the Cuban capital in 1925.

Fresh from illustrious commissions in Paris, Seville and Barcelona, Forestier spent the next five years designing shady tree-lined avenues, classical plazas and a harmonious urban environment that highlighted Havana’s important monuments and lush Caribbean setting.

Machado’s dream

Forestier had been invited to Cuba by Carlos Miguel de Céspedes, the public works minister of President Gerardo Machado.

Remembered today for his dictatorial tendencies and untimely fall from grace, Machado started his eight-year tenure (the so-called Machadato) with a bold programme of public works that included the construction of a cross-country highway and a glittering new parliamentary building – the Capitolio Nacional – inspired by Paris’ pantheon.

In common with other ‘strongmen’ leaders, Machado was adamant to stamp his personal mark on Cuba. Looking to attract US tourists fed up with the asphyxiating restrictions of Prohibition, he dreamed of turning the new republic into the Switzerland of the Americas crowned with a capital punctuated by monumental buildings. ‘When it comes to my political legacy, save your words and ink, the stone and marble speak for me and mine’, he later wrote.

Fortunately, money wasn’t in short supply. Flush with cash from Cuba’s sugar industry and generous loans from deep-pocketed US financers, Machado pumped US$17 million into the Capitolio. But the huge neoclassical legislature was just one piece in an ambitious jigsaw. To execute the rest, the president needed outside help.

The Havana Masterplan

Well into his 60’s by the time he arrived in Cuba in 1925, Forestier was a veteran of numerous international assignments including the redesigning the Champs-de-Mar, the grand gardens beneath the Eiffel Tower.

His work in Paris with engineer, Adolphe Alphand gave him a direct link to Alphand’s mentor Baron Haussmann, the urban planner who had transformed the French capital from a medieval slum into the elegant ‘City of Light’ starting in the 1850s.

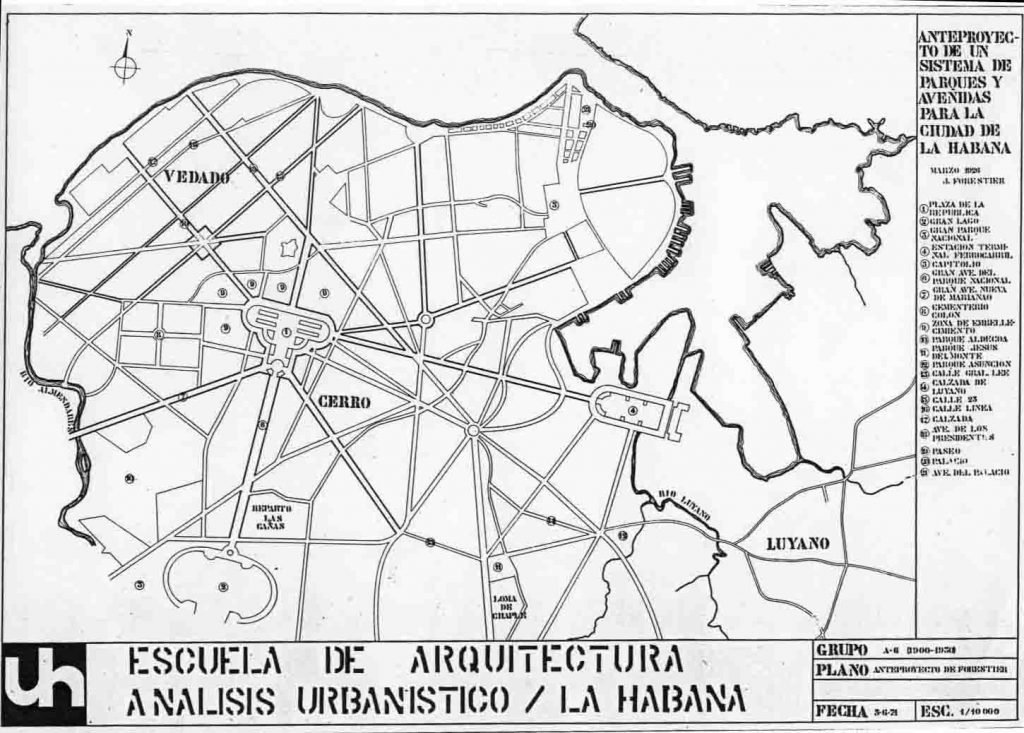

During his first trip to Havana in 1925-6, Forestier flew in an airplane above the city to get a better perspective of its size and layout. Collaborating with a mixture of French and Cuban planners including leading Cienfueguero architect, Pedro Martínez Inclán, he subsequently drew up a masterplan, the ‘Plan Director de la Habana’, that proposed upgrading large parts of the city with wide boulevards, manicured parks, and grand civic buildings. The aim was to make Havana more liveable and salubrious, a modern city that could lure tourists, attract international attention, and promote Cuba as an ambitious independent republic.

Forestier’s style drew on French beaux arts, the American City Beautiful movement, and the British Garden City movement. Like Haussmann in Paris, he saw green spaces as essential in curtailing overcrowding, enhancing recreation possibilities, and bringing elements of the Cuban countryside into the city.

The crux of Forestier’s plan was to ultimately move Havana’s civic center from overcrowded Habana Vieja to the Loma de los Catalanes (today’s Plaza de la Revolución), a low hill then home to a small chapel. The hill was earmarked for a monumental civic square from which broad avenues would radiate toward the Malecón, the airport and the port in the manner of Paris’ Place de Étoile.

Interconnecting parks and boulevards

Before he could enact his macro-plan, Forestier was commissioned to undertake the more immediate task of designing the gardens surrounding Machado’s new Capitolio. Incorporating native Cuban flora, including royal palms, into an ordered linear layout reminiscent of Versailles, the Frenchman cleverly blended classical beauty with elements of Havana’s diverse natural environment, a technique that would become his hallmark.

In the rectangle of land directly to the south of the Capitolio, Forestier was invited to turn an old parade ground into the Parque de la Fraternidad. Inaugurated in 1928 for the prestigious Sixth Panamerican Conference attended by US president, Calvin Coolidge, the park was centered around a Ceiba tree planted with soil from 28 American countries.

Next, Forestier set about beautifying the Prado, Havana’s main boulevard. Lined with dense trees, ornate streetlamps, and marble benches, the promenade was embellished with eight bronze lions that guarded the two main sections of the thoroughfare.

Walkways and gardens were applied to the Avenida del Puerto, another esplanade that ran perpendicular to the Prado starting at the jaws of the harbor. Similar treatment was given to Avenida de los Misiones a wide boulevard that swept from the recently finished Presidential Palace down to the harbor mouth.

With his initial work complete, Forestier had succeeded in creating a continuous line of greenery through Havana stretching from Parque de la Fraternidad, along the Prado, to the port, a vast social space where Habaneros could meet, greet, walk, and talk.

Unfinished projects

Forestier had even bigger green plans for the Vedado neighborhood where he dreamed of installing an expansive city park. The green space – ambitiously coined the Gran Parque Nacional – never came to fruition although part of it later materialized as the Parque Metropolitano, the thin slice of urban forest that hugs the banks of the Almendares River.

At the still new university campus, he drew up plans for a dramatic entry staircase and a belvedere (lookout garden). The belvedere was ultimately abandoned, but the staircase – still affectionately known to thousands of Cuban students as ‘La Escalinata’ – was built by Cuban architect César Guerra in 1927.

Forestier’s legacy

While Forestier made plenty of character-changing adjustments to Havana’s urban landscape during three separate visits to the Cuban capital in the 1920s, many of his plans were unhinged by the economic crash of 1929, the fall of Machado, and the landscaper’s own death in 1930.

His unfinished dreamscape lay dormant for two decades, although many of his proposals were revisited in the 1950s when Havana, with additional input from Cuban architects and planners, ultimately shifted its civic center to the Loma de los Catalanes. The contemporary Plaza de la Revolución capped with a 112m-tall memorial to José Martí designed by Aquiles Maza and Juan José Sicre stands at the terminus of several Parisian-style boulevards, including Avenida de los Presidentes (Avenida G) and Paseo.

Today, scores of Habaneros, from the taxi drivers who park in Parque de la Fraternidad to the school children who play games on the shady walkways of the Prado, still enjoy the fruits of Forestier’s bold green vision. Havana is a much richer city for his work.

***

Note:

Bibliography used: “Dictator’s Dreamscape: How Architecture and Vision Built Machado’s Cuba and Invented Modern Havana”, de Joseph Hartman (2019).