Last December 8, Day of the Immaculate Conception for Catholics, and Iroko for practitioners of the Regla de Osha, 118 years were commemorated of the birth of what is undoubtedly the most universal of Cuban painters: Wifredo Lam, universality which is given to him not only by the fact that he is the one of greatest international importance, but also because, in his work, like in no other, some of the predominant elements in the configuration of our collective identity, of African, European and Asian ancestors, are synthesized., amalgamated in a symbolic corpus of great visual singularity.

Iroko is the orisha with the most intimate relationship with the ceiba. According to tradition, he is a saint of travelers, and intervenes in the realization of noble and not so noble wishes. The Immaculate…well; we know almost everything about the Immaculate.

The Havana Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center (CACWL) took the opportunity not to tie a red cloth to the trunk of our sacred tree, nor to offer it, at the foot of its roots, a white rooster, but instead wanted to celebrate the birthday of the creator of The Jungle with an exhibition of 21 drawings made by him on paper between 1940 and 1955, and which in 1958, when the artist closed his Havana studio house, on Avenida 76, in front of what is now Ciudad Libertad, left in the custody of the family. The exhibited works, which are part of a corpus of one hundred pieces, make up the Castillo Collection, currently in the care of Juan Castillo Vázquez, Lam’s great-nephew.

As far as we know, these small and medium-sized pieces were kept for 30 years in “a voluminous folder, behind a piece of furniture,” and they became publicly known with the inauguration of the CACWL, on December 8, 1993, when they integrated a temporary exhibition.

Thanks to the efforts of the recently deceased Cuban curator Ricardo Viera, in 2017 the Lehigh University Art Galleries Teaching Museum, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, exhibited the same selection of works that today, recently restored, we can see in Havana, in what was considered the first sample of a private collection from Cuba in the United States, since 1959. In addition, part of the Castillo Collection has been seen in Belgium, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Spain, Romania, Mexico and Martinique.

Papers are papers

I confess to being a devoted admirer of Lam’s work on paper. I have had the opportunity to contemplate, enchanted, The Jungle (1943), La Silla (1943) and other significant pieces by this artist that are housed in various museums in Europe and America (from the deep south to the cold north). I always look for them; although sometimes they are the ones who come my way in the least expected places. But none of them produces in me as much of a discharge of “aesthetic adrenaline” as the pieces on kraft paper that the Havana National Museum of Fine Arts treasures.

I know that what I say may seem heretical to some, but what are we going to do? Here I speak of taste, of that mysterious and endearing relationship that is established or not between the viewer and the work. Let’s say, to finish condemning the purists, that I prefer the two chairs that precede La Silla. La chaise (Paris stage), gouache on paper and La Silla (1942), oil on kraft paper, have the charm of irresolution, of the pure gesture, of the outburst of joy that good jazz players experience when, instead of playing, they live the music. I love the process more than the culmination.

Between outbreaks and more outbreaks, autochthonous transmission and counter-outbreaks of the COVID-19 epidemic, I was hunting for the opportunity to enjoy Wifredo Lam. Drawings 1940-1955. Finally, one morning this January, before the museums and galleries closed again to avoid contagion, I entered the lonely room. I suppose that, since the inauguration to date, very few of us have had that luck. I hope that the organizers, who have planned the closing of the exhibition for the 30th of this month, will have the courtesy to extend it until the epidemic calms down. It would be a shame if, to use an endearing term for Lezama, this intimate, on-camera event was to pass almost without “resonance” for the Havana public.

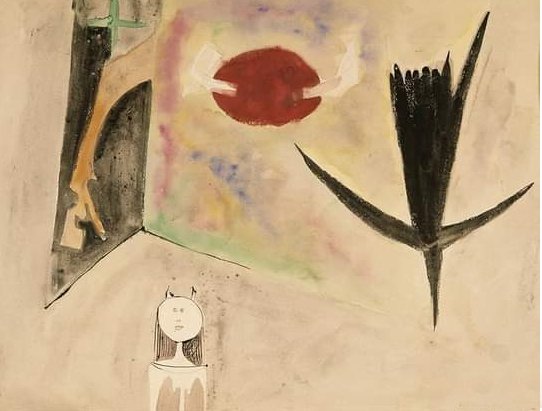

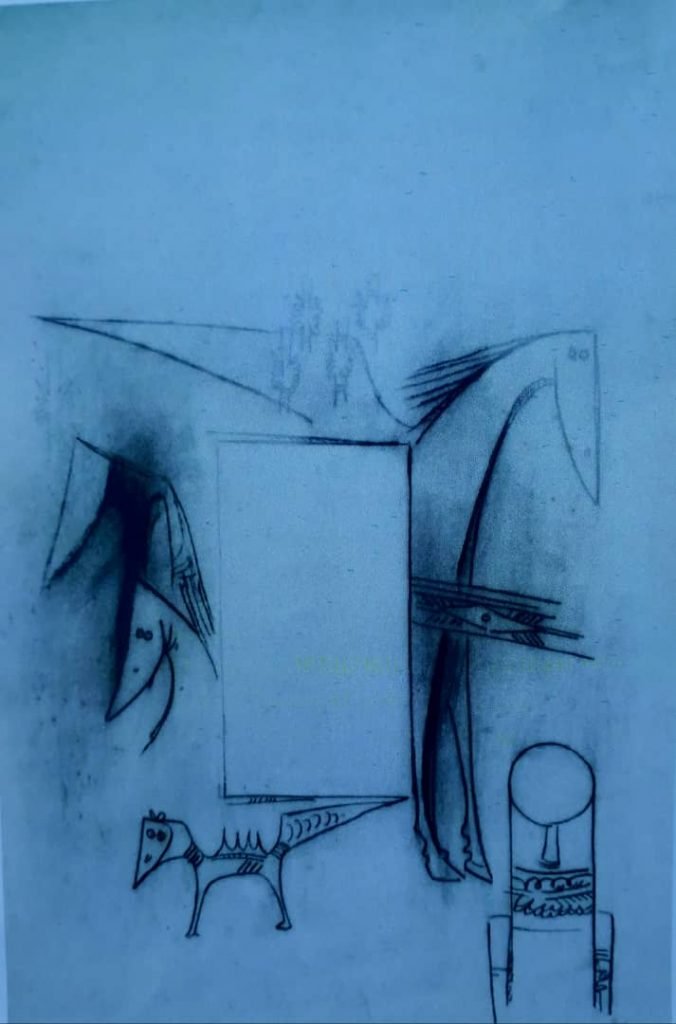

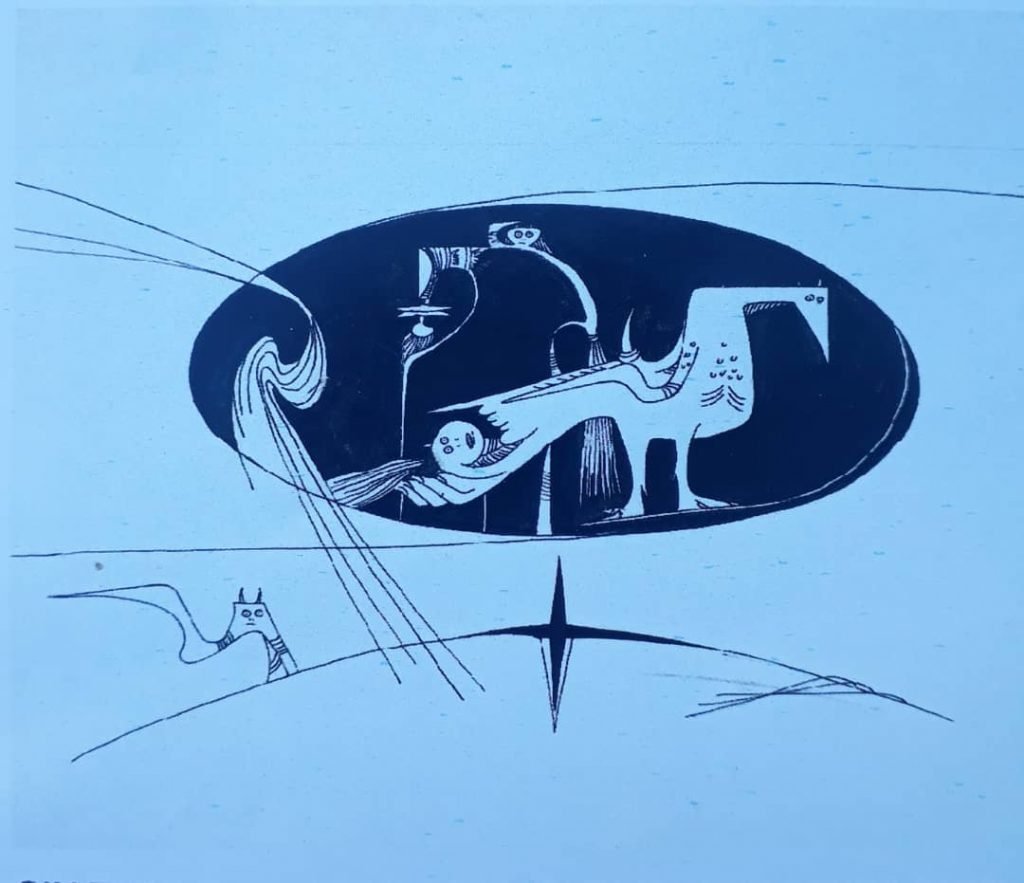

From what I saw there, I was more interested in Figura con luna (ca. 1947), Figuras y rectángulo No 1 (ca. 1947), Figuras (ca. 1947, ink wash and watercolor on paper) and the prodigious untitled (ca. 1953, pencil, ink and tempera on paper), where the color, applied in an almost blurred way, serves as an appoggiatura (musical?) to the powerful black bird, to what appears to be a horse’s leg in the background, and to the recurring little figure—a güije? —that looks at us from the front, with a squinted gaze.

In Figuras y rectángulo No 1, we can see the attempt to contrast the rationality of geometrism (an allusion to the assumed coldness of concrete art?) with the hallucinated, dreamlike world that characterizes Lam’s work. We will never know if it is a sketch for a later piece or a composition study. The truth is that it is disturbing, as if the rigid figure tried, without success, to bridle the winged horse in the background.

It is striking that none of these small and medium-sized format works bear the artist’s signature. I found the explanation in the catalog that was published for the celebration. From what I read there, it can be inferred that Lam signed his works when they were to be acquired, but it is also known of large-format works that, by mistake, were not signed, although their authenticity is more than proven. The latter, Juan Castillo tells us, is evidenced by the monograph that he dedicates to WL Max-Pol Fauchet, published during the master’s lifetime, and where more than one painting appears with that singularity.

Lam, trying to define his indefinable art, has been given various labels. That he frequented the surrealist movement does not mean that he ended up ascribed to that trend. To top it all, in an encyclopedia I just saw that they point to The Jungle as an example of abstract art…. For me, Lam’s work, if it were imperative to define it, is realistic; only it does not allude to the surface of the encoded “reality.” The mythical world from which he bases his work, armed with his experiences as a child from Sagua la Grande, the son of a mulatto and a Chinese, who listened to invocations and prayers to the deities of the Yoruba pantheon in his light sleep, is, without further ado, one of the many faces of reality for many on this shore of the planet. Here the orishas are fed so that they plant our paths of good vibes, and they are reprimanded, and even punished, if they don’t comply. The saints handled by the Regla de Osha, like the Greek gods, have human appetites, anger and kindness. They can be fickle and protective at the same time. I like to believe that they feel very comfortable within the magical Lam-style representation.

Wifredo Oscar de la Concepción Lam y Castilla was born, as I said, on the day consecrated to Iroko and the Immaculate. Can anyone not see a magic flash in this “fortuitous” event?

***

Note: The information to write this review was taken from texts by José Manuel Norceda, Juan Castillo Vázquez and Nelson Ramírez de Arellano, provided by the Communication Department of the CACWL.