Arriving in New York is entering a universe of symbols, nourished by literature, film, photography and by those who left their mark on the city. Without having set foot there, we think we know it; and when we finally walk its streets, rather than discover it, we go out in search of those emblems.

For a Cuban like me, the personal priority came before other icons like the Statue of Liberty: finding José Martí. So, a few hours after disembarking, I took Sixth Avenue — Avenue of the Americas — to 59th Street, at the south entrance to Central Park. There, flanked by the liberators José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar, Cuba’s Apostle awaited me.

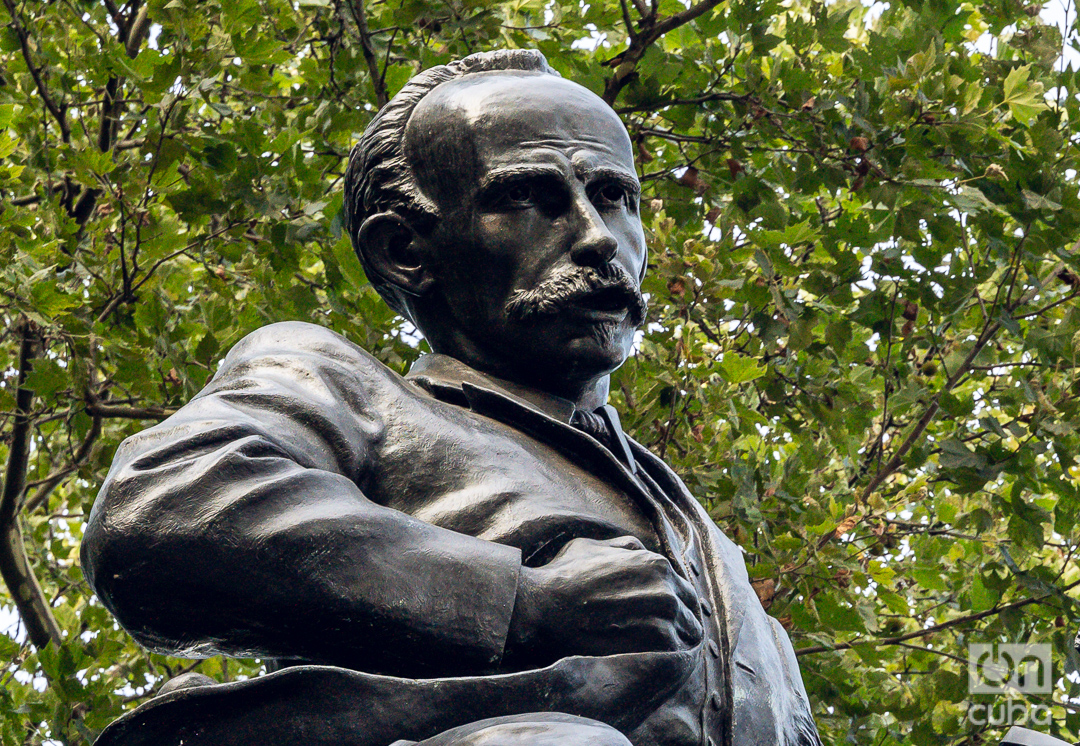

Standing nine meters tall, Martí rises on horseback, in bronze, on an imposing black granite pedestal. The steed rears up, standing on two legs; the combatant’s body falls to one side with his hand to his chest, his gesture pierced by the pain of the gunshots. Facing this motionless flash of lightning, one understands that the sculpture narrates a moment and, at the same time, a biography: the man who organized the necessary war from New York and fell at Dos Ríos on May 19, 1895, just six weeks after returning to Cuban soil, determined not to ask for exemptions from the sacrifice he preached.

It represents his death in battle, but to me it seemed the opposite: a scene from life. I arrived at noon, in the stifling heat of a New York summer. The sun at its zenith bathed the sculpture head-on, as if responding to his own verses: “I am good, and as good / I will die facing the sun!” The piece stands with its back to the forest — as if emerging from it — and, from the front, faces the city’s skyscrapers.

The whole weighs what metaphors weigh when they become matter: tons. The inscription in the granite reads: “Apostle of Cuban independence / leader of the peoples of America / and defender of human dignity.…”

Martí lived fifteen years of exile in that city. It’s easy to imagine him crossing the same avenues, finishing off articles in Manhattan cafes, writing letters and forging alliances, convinced that the war had to be for everyone or it wouldn’t happen. For him, New York was an editorial office, a platform and a temporary home; for thousands of Cubans later, it has been a mirror, a stage for arguments, reconciliations and nostalgia.

The work’s creator, Anna Hyatt Huntington, began sculpting it at the age of 82. The widow of Archer M. Huntington — the founding Hispanist of the Hispanic Society — she modeled Martí on a farm with lakes that reflected the profile of the hills.

Her process began with clay modeling, followed by plaster casting and culminated in bronze casting using the lost-wax technique. The casting was carried out at Domico Scoma Bronze Works in Queens, which specializes in large formats. The pedestal was designed by the architectural firm Clarke & Rapuano and constructed of dark Barre granite, with carefully chiseled inscriptions in both languages.

Cuban journalist José Antonio Cabrera traveled in the summer of 1957 with photographer Osvaldo Salas — then a correspondent for Bohemia magazine in New York — to report on the piece while it still needed to be sent to the foundry. Hyatt Huntington disliked the publicity and was on the verge of refusing to speak, but agreed because, she said, “Cubans have the right to see what I’m doing with their hero.” She learned to love Martí out of love for her husband and through the mediation of Cuban friends in the city; also out of her own conviction: she saw in him an intellectual spirit of rare sensitivity. It wasn’t a statue for the sake of ceremony; it was a dialogue.

By the end of 1958, the bronze Martí statue was ready to be unveiled. However, the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in January 1959 halted its installation: New York authorities preferred to put the decision on hold. For six years, the sculpture waited in darkness in a Bronx warehouse, while layers of political and symbolic dispute accumulated outside.

In October 1964, a group of exiles attempted to place a plaster replica on the site; the police immediately removed it. The figure remained decapitated on the asphalt. Finally, in May 1965, after sustained pressure from the Cuban exile community, the city authorized the installation of the bronze original. It was the provisional closure of a cultural and diplomatic battle in which public art served as a language of resistance, identity and memory. Anna Hyatt Huntington, 88, attended the ceremony.

It was a short truce, as the exiles and the Havana government regarded each other from irreconcilable shores and disputed — and continue to dispute — Martí’s legacy. Yet the bronze doesn’t take sides based on circumstances, but rather captures a moment that overwhelms us all.

Martí doesn’t pose as a marble hero: he falls in battle. He doesn’t preach: he pays. And behind that fall is the man who conceived America — the one that speaks Spanish and the one that is invented every day on these avenues. His independence wasn’t just about borders: it was about tone, ethics, the precision with which he named what others disguised.

During my week in New York, I returned to the statue three times to contemplate and photograph it. That bronze closed a circle for me: the exile who loved the city — with its shades of gray, its pros and cons — as a laboratory for the world; and the city that, in its own way, returns him to the map of essential symbols.

However, although I went in search of a

symbol, I found a mirror.