In my father’s library there is a very old, carefully bound magazine that caught my attention. Its title and information are: Archivos del Folklore cubano, Fernando Ortiz, Volume IV, Havana, Cuba, 1929. I looked in the index and found one of his articles on a topic still remembered among Cubans today: “Matías Pérez. Personaje Folklórico” (Matías Pérez. A Legendary Figure,” by Herminio Portell Vilá.

Then I remembered Boloña’s Muestrario del mundo (World Sample Book) or Libro de las maravillas (Book of Wonders), compiled from the catalog of Don Severino Boloña. My father wrote this book when we lived in Arroyo Naranjo, in 1967. He cut out the vignettes and placed them on the page. It’s a curious collection of poems that younger generations no longer know, and it contains poetry and short prose texts.

Among the vignettes he found was one of a hot air balloon, and Dad decided to pay a small tribute to the daring Portuguese man, a professional awning man (“the king of awnings,” they called him), whose story always impressed him.

In his short but exhaustive article, Portell Vilá, a great Cuban historian of the last century, tells us:

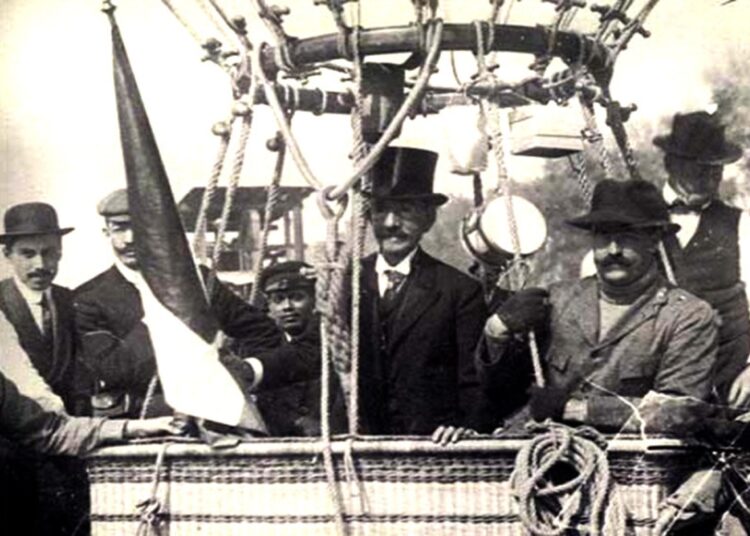

“The first ascent in Cuba in a hot air balloon was on March 19, 1828, by the aeronaut Eugenio Robertson and his wife Virginia. A few years later, on January 31, 1831, Domingo Blinó made another successful ascent…. Several years later, on March 1, 1856, Mr. Phillip Godard, an expert aeronaut who was in Havana with his wife, made a balloon trip with great ease. His balloon took off from Campo de Marte, rose to 12,000 feet, and touched down in Cotorro after 48 minutes of flight. Mr. Godard made up to six more ascents. Many accompanied him on these trips, among them Matías Pérez.”

Portell Vilá continues by recounting that Matías Pérez, who seemed to have a true fascination for flight and was somewhat adventurous, felt he had learned enough to move from passenger to pilot and proposed to Mr. Godard to buy his balloon, called Villa de Paris, with all its accessories, for $1,200. On June 12, 1856, he made his test flight, which ended without incident, in the Cerro neighborhood.

Matías Pérez became very popular for his daring exploits and became known throughout the island. He wanted to break records for duration, flight length and altitude, like those in Europe, and his flights aroused great enthusiasm. The flights took off from Campo de Marte, today Fraternidad Park.

On July 29 (other sources claim it was June 29), 1856, Matías Pérez set the date for an ascent, announced “with great fanfare.” He would depart in the afternoon from the Campo de Marte, as was customary, and he intended to break several records. The weather was not good, there was a lot of wind and the flight had to be postponed for several hours, but Matías Pérez, stubborn and reckless, decided to go ahead.

“From the fragile basket of his balloon, he gave the orders to release it, unloaded some ballast and the aerostat quickly rose until it disappeared into the clouds, on that fateful journey from which it would never return,” Portell Vilá recounts.

My brother Rapi, like our father, was impressed by this story: that obsession, that tenacity to achieve a dream even at the risk of one’s own life. And he created a kind of graphic prehistory of an imaginary Matías Pérez as a child, which he titled Matías Pérez en busca del viento (Matías Pérez in Search of the Wind).

The first two drawings show a boy in a forest, trying to catch the wind. Although the drawings are just that, they convey a mystery, a strange anguish. I don’t keep them; they’re in Mexico. I’ve had the other one in my room for years. It shows a very sad boy, holding a balloon in his hand, and the string holding it up looks like it’s about to break.

I accompany this work with that drawing, the Boloña vignette and my father’s text.

***

An ascent in Havana

By Eliseo Diego

Matías Pérez, Portuguese, a professional awning man, who was in the vast airs that you went for them, Portuguese, with such elegance and haste. In magnificent verses you said goodbye to Havana’s young ladies, and then, one afternoon when the weather was raging, mocking prudence, and while the military band thundered on the Campo de Marte, you flew up into the air, an avid Portuguese, an Argonaut, leaving behind your umbrellas and handkerchiefs, higher still, to the region of transparent solitude.

How far away the tiny rooftops of Havana seemed, and your six bodies higher than its towers and palm trees, how you flew with the fury of the wind, Portuguese, that last afternoon!

And when, at the mouth of the river, having been swept far below by that same fury of the air, the prudent fishermen called to you, shouting to you to come down, that they would look for you in their boats, did you not answer, frenzied Portuguese, throwing your last burdens over the fragile side?

There you went, Matías Pérez, Argonaut, toward the sad, leaden clouds, first skimming the enormous waves of the eternal other, and then higher and higher, while you threw everything overboard, on your lips a foam too bitter!

Bold, impetuous Portuguese, where did you go with that unbridled impatience out to sea, leaving us only this expression of ironic disenchantment and Cuban sadness: he went like Matías Pérez!

Fleeing swiftly toward a glory too transparent, toward a glory made of pure air and nothingness, through which your balloon was lost like a little cloud of snow, like a seagull now motionless, like a point already itself transparent: he went like Matías Pérez!