“His chest is made of plaster” Diego Maradona illustrated with his innate originality the inexperience of a player who tried to catch the ball at chest level and bounced it three meters.

The phrase froze in my memory 20 years ago, sitting behind him in the guest box of the Pedro Marrero stadium in Havana.

Maradona had arrived in Cuba three weeks earlier, on January 18, 2000, for treatment for his cocaine addiction, which, weeks ago, had caused him a dangerous hypertensive crisis and ventricular arrhythmia during his vacation in the Uruguayan resort of Punta del Este.

He appeared in the Cuban stadium, with his more than 120 kilos of weight, dark glasses, shorts, sports shoes and hair dyed yellow, accompanied by his father, to kick off the finals of the national championship in which Pinar del Río would beat Havana two goals to one.

People from the stands cheered him when the former Argentine team captain entered and left the field. That afternoon there had been one of the few good turnouts for a domestic game so far this century.

Forty-eight hours earlier he had told me, during a meeting with veterans and local soccer managers, that he was desperate to play: “I see a ball and I go crazy.”

Four months later, he would fulfill his wish. I would be lucky to be involved.

The “Pelusa” had lost some weight and with the treatment applied, the doctors authorized him to play again.

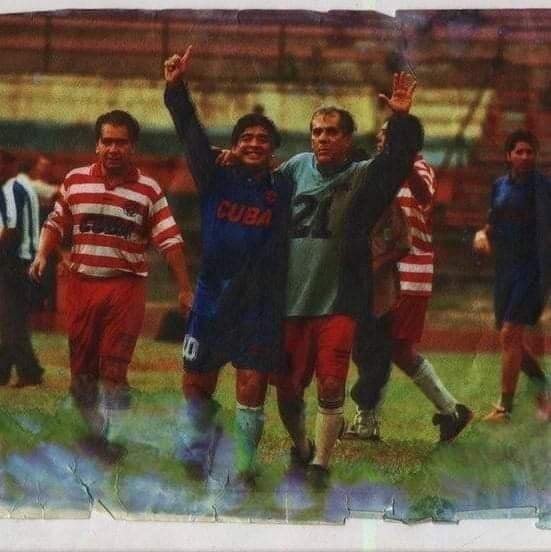

On June 7, 2000, with the help of his manager Guillermo Coppola, a game was organized between “Friends of Maradona” versus “Foreign Press,” including some officials of the National Federation.

In line in front of the semi-empty grandstands, we wait for Diego and his colleagues to welcome them with the necessary claps. It was, after all, the “international comeback” of the Pibe. I, for my part, had returned to the field I had known from childhood.

Among his friends who arrived from Buenos Aires was the musician Rodrigo Bueno, known as “El Potro,” who had traveled to the island so that Diego would hear for the first time a song in his honor, “La Mano de Dios,” which would later become a global success:

“Shortly after he debuted/“Maradó, Maradó”/ the 12 was the one who chanted /“Maradó, Maradó”/his dream had a star /full of goals and dribbles…/and all the people sang: “Maradó, Maradó”/the Hand of God was born/“Maradó, Maradó”/ filled the people with joy/watered this soil with glory….”

The “Potro” would play in central defense that afternoon. Two weeks later he died in a traffic accident on a Buenos Aires highway.

A downpour accompanied us most of the game. At the start of the second half, I changed position and went to goal. Before, I asked Diego to get together for a photo.

Minutes later he would claim the favor: he had to execute a free kick from 15 meters away, using his hands, he set the ball well on the wet ground, and fired a missile with his prodigious left foot to the left corner. I didn’t see it go by.

Diego jumped up and down and looked at the sky with his arms raised, as if it were one of his goals against the English in Mexico 86.

It was his first goal in I don’t know how long. And I’m most proud of that “pepinazo.” The game ended 6-0, two from Pibe. Another “downpour.”

With the final whistle, we all gathered in a corner of the field for a family photo with Maradona in the center, exclaiming “a beer please!”

I was left with the desire to at least take home the shirt of that unforgettable game.

Since his arrival in Cuba―a stay that was thought to be for a few months and lasted from 2000 to 2005 with intervals―Maradona spoke several times of his willingness to directly help the national team.

Despite the publicity blow his presence on the island represented, I never heard that the idea was well received by the soccer authorities. And I think not only because of resentments about putting the national teams under Maradona’s command; the Argentine was a severe critic of the president of FIFA, the Swiss Josep S. Blatter.

This was his third visit to Cuba, but under conditions very different from those of July 1987 and December 1994.

On the second occasion, I took a break from the end of the year preparations and arrived at the Hotel Nacional, where he was staying with his family and the rest of his entourage, among whom was Guillermo Coppola, actor Ricardo Darín and the Argentine journalist who had been in charge of promoting the idea of a number 10 Albiceleste shirt signed by Diego and other players dedicated to Fidel Castro.

It was December 29, at noon. I had made several unsuccessful attempts to enter the pool where the “Argentine party” was taking place.

I was about to give up and forget about my questions about his positive doping at the World Cup in the United States when Barcelona Olympic champion and world record holder Javier Sotomayor and Roberto Moya appeared in the hotel lobby.

Moya had won an Olympic bronze medal in the Catalan Games, in the discus throw. Unfortunately, in May 2020, at the age of 55, the Havana athlete passed away suddenly in Valencia, Spain.

Well, with Sotomayor at the helm, I got my visa to enter the pool. I was there all afternoon listening to the anecdotes of the champions, between beers and shrimp. Diego’s admirers came from time to time to greet him, among them Italian journalist Gianni Miná and Cuban singer-songwriter Augusto Enríquez.

The next day I learned that Maradona would close the day after midnight, at the disco, with a new olive-green cap on his head, autographed.

Seven years later told Coppola to call me for an interview at the Pradera hotel-sanatorium, where he was being treated by neurologists, cardiologists and nutritionists.

That night I had my son Michel, who at the time was studying Social Communication at the University, accompany me. Diego’s “exclusive” was to show me his new tattoo: the face of Fidel Castro on his left leg.

But there was more. Taking advantage that I was a journalist for the newspaper Granma, he wanted to make public his interest in getting a house in Cuba, rented or bought. He never received a reply; at least affirmative.

Michel and I took a photo with the player-history. I returned to the newsroom ready to type the unpublished material.

“Don’t make it long” was the reception. How many newspapers at that moment would have wanted to have this entire scoop? No way. I decided then to send my extended version to the Mexican sports newspaper ESTO. From then on, I started doing that.

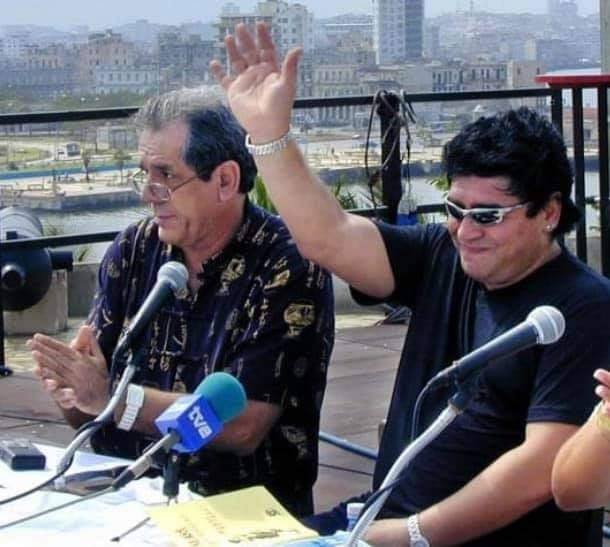

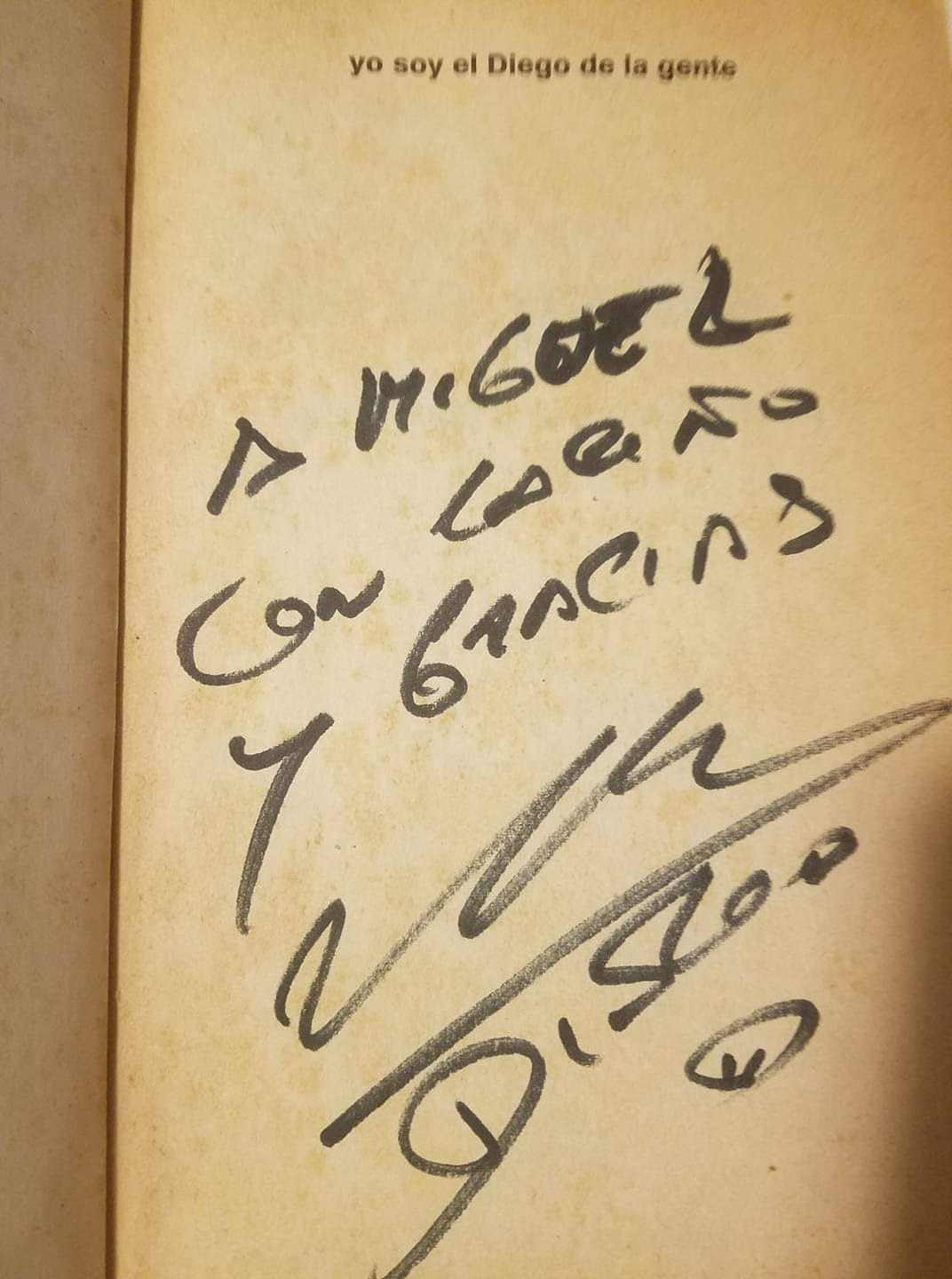

Shortly after, on February 16, 2002, I had the privilege of presenting his book Yo soy el Diego de la gente at the traditional International Havana Book Fair.

Hundreds of people were waiting for him in front of the stand. He entered through a corner of the Plaza de San Francisco of the old Morro Cabaña colonial fortress, facing the Havana bay.

He was breathing hard after climbing the stairs, at the foot of which the black Mercedes Benz that brought him had parked. He was wearing dark shorts and a black T-shirt, with sunglasses and a ring in his left ear.

I spoke to the public briefly. I remembered, when reviewing the biographical text, that the first ―and last―time his name appeared in the press it was misspelled: “Caradona” instead of Maradona.

“I could not be absent in this presentation of my book, which had its beginnings in Havana. I am very grateful to all Cubans,” he said and showed his tattoos. He announced that he was donating the rights to this edition to Cuba, with a sale value of 20 Cuban pesos.

The first edition, published in Argentina in 2000, sold out in a week.

In this Havana event he signed numerous copies and left to applause from the people, who shouted “Argentina champion.” Four months later it would be the World Cup in South Korea, in Japan.

Those are the moments that go through my mind in this “first time” with El Pelusa. After further relapses, he would return to Havana in 2004, under a more severe regime, which was short-lived, in the Mental Health Center administered by the Ministry of the Interior.

Then he would return regularly.

The last time I wrote about him was a few days ago, when I voted him, along with Pelé, Di Stefano, Zidane and Iniesta, among the offensive of the Dream Team of All Time in the world contest of the magazine France Football. I have been a member of the Ballon d’Or jury since 2007.

On December 17 the result will be announced.

Earlier this year, Maradona’s lawyer announced that “El Pelusa” would travel to Cuba to legally recognize three children he had with two women. With these new members, his offspring would number eight. A South American newscast today speculates that it could reach 11.

But the new trip to the island was suspended. Death dribbled many times, but this time his body could not take it anymore.