Cuban writer Leonardo Padura, Princess of Asturias Award for Literature (2015), considers his novels to be “one of the most radical documents that could have been written” about a Cuba today in turmoil, whose problems “must be resolved among Cubans.”

“I believe that my novels written and many of them published in Cuba, such as The Man Who Loved Dogs, Herejes or La novela de mi vida are among the most radical documents that could have been written and said about this country. And that gives me a lot of peace of mind,” the author said in an interview with EFE.

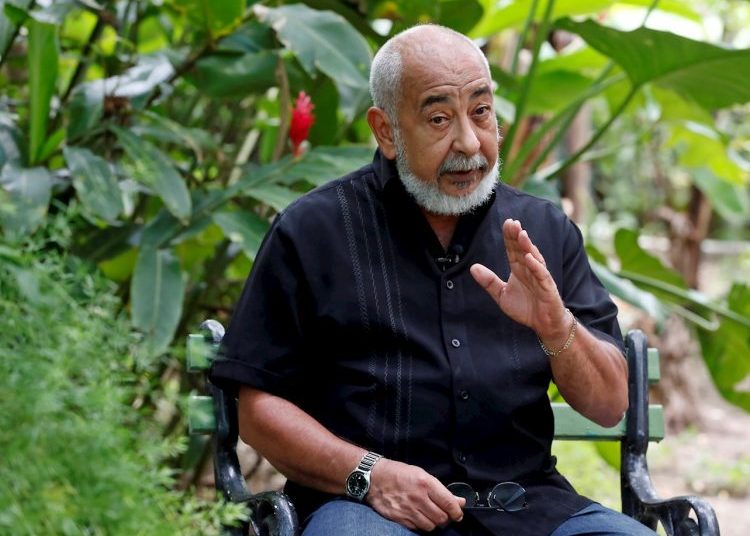

At his family home in the Havana neighborhood of Mantilla, three weeks after thousands of people took to the streets of the country to protest the scarcity and demand freedom, Padura reflects on the extreme polarization that the island is experiencing, about which he hopes that “it can be resolved among Cubans,” including those in exile.

“With some frequency, I receive attacks from one extreme and the other, because I try to be fair and speak of truths about which there is a certain consensus. It is already known that the truth is not absolute, what is absolute is the lie. And in none of my texts, or in my novels or journalistic works, do I need a lie to talk about Cuba,” he said.

And it is that the also academician of the Language considers that “when someone wants to criticize Cuba they don’t have to exaggerate, they only have to tell the truth.”

“I’m very at peace with myself, I cannot satisfy all positions, I don’t want to put myself in any extreme, I am very afraid of fundamentalisms and extremes because they start from the fact that their reason is the only possible reason, and I believe that there is always more than one reason and it’s necessary for there to be a dialogue between these reasons,” he said.

The protests caught Padura watching the Eurocup. “Suddenly the transmission is cut off and the president (Miguel Díaz-Canel) starts speaking and I find out what is happening.”

Shortly after, the authorities blocked access to the Internet and the information that came in was confusing and “very distorted, very partial, very aggressive in some cases and it was difficult to find out what was happening,” he recalled.

His first sensation, which he described the week after the demonstrations in a text published on the La Joven Cuba platform, “was that there had been a scream that came from the entrails of a society that demanded other ways of managing life in a meaningful way in general, and that is where the economic, the social, the political comes in….”

The unjustified delay in economic reforms generated “something that is evident”: the growth of inequalities and poverty, reflected in the novel La transparencia del tiempo.

Thus, Padura mentions very poor settlements in Havana in which “you realize that this is not the country for which we have worked, which we have dreamed, for which so many sacrifices have been made. We must find solutions for these people….”

The demonstrations, in his opinion, channeled the weariness of waiting for a prosperity that never comes and evidenced the lack of communication between power and how citizens feel.

“So much so that I think they were surprised by that demonstration because it was not that some people had started shouting something in a queue, it is that in many parts of the country there were people who came out to ask for things, to ask for freedom for example, and it is very serious when people scream for freedom.”

The writer is concerned that this feeling “is not understood and processed in the best way, because there is a social magma in which there are these intolerances and extremes of which we spoke at the beginning that may be the ones that prevail and it would be the worst.”

“The violent responses are not at all the cure that this country is needing, which is not the same as it was until 15 days ago. It is a different country and you have to handle it in a different way,” he affirmed.

He also points out that what happened was already in the making, as demonstrated by the concentration of young creators on November 27 before the Cuban Ministry of Culture.

“There they spoke of the need for a dialogue that in the end was left in a few words and very few solutions, and when people ask for freedom of expression, thought, opinion, they are asking for something that belongs to them, something that I don’t think can be denied to them in any system or in any country,” the author emphasized.

Regarding all those young people who protested on July 11, Padura warns that the “less desirable” alternative is for them to be marginalized or “even imprisoned for their social or political position” and that due to the prolonged “bleeding” suffered by the island many — among them the most prepared —end up leaving.

The author, who in 1996 became the first “independent writer” in Cuba, believes that what happened now will be reflected in his literature, although “perhaps not directly.”

“I have tried to practice my independence and my freedom for many years. I think that for any creator the need for freedom of expression and thought is fundamental,” although with limits regarding “homophobic, xenophobic attitudes, attitudes that are somehow fascist.”

“In addition, life is too short for us to be limiting ourselves in as many things as we have to limit ourselves due to the social contract that exists,” he concluded.