As reported by the Cuban government on June 11, the post-COVID-19 strategy will consist of two stages: recovery―return to normality, avoid new outbreaks, develop coping capacities and reduce risks and vulnerabilities―and the strengthening of the country’s economic activity. The latter will include adjusting the 2020 and 2021 Economic Plan, strengthening savings, generating more foreign exchange earnings, using more of the country’s resources in a more efficient way, and boosting national production, particularly food.

President Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez has insisted that Cuba will resume the course of updating the economic and social model, outlined since 2010 in the documents of the Party and the government.1 Díaz-Canel stated that, to face the crisis caused by COVID-19, “we have to come up with different things…we can’t continue doing things the same way.” He stressed the need to direct the work of the Permanent Commission for Implementation and Development, in order to evaluate “how, in a faster, more determined, more organized way, we implement a group of issues that are pending implementation in the Conceptualization of the Economic and Social Model.” Among the elements that have not yet been implemented, he mentioned some forms of management and ownership. Also, the resizing of the business and private sectors and the adequate relationship that must exist between the two, of which, he pointed out, “we have good experiences in these times of pandemic.”

Although details have not been disclosed, there are indications that this will include, among other measures, giving a boost to the private sector―perhaps by expanding the list of activities authorized for self-employment or establishing one of banned activities, allowing the others―and some possibility of creating private small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Thank god. However, it doesn’t seem they’re going to approve new industry and service cooperatives, misnamed “non-agricultural,” improve existing ones or modify the Ministry of Agriculture’s centralized management regime for agricultural cooperatives. Regrettable, if it is so.

Based on these ideas, the objective of this two-part series is to unveil the impacts of the new and necessary measures on existing economic and social inequalities and to demonstrate that, by consciously and articulately adopting the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), the country would have more tools to face inequalities and boost inclusive local economic development, within the framework of the construction of socialism.

Increasing inequality

The 1990s crisis forced the country’s leadership to adopt a series of policies that shook the basically egalitarian society built in the first three decades of the Revolution. Along with opening up to tourism and remittances, temporary and return emigration, communications, internet access and the emergence of a private sector in which one part struggles to survive while the other enjoys comfortable and even luxurious living standards, levels of inequality have been generated that did not exist in the past decades. These measures revitalized the economy, diversified employment, increased the insertion of Cubans in the world, expanded transnational family networks and made it possible to overcome the crisis, while many improved their material standard of living.

The tools and policies to face inequalities in a more diversified and complex society, however, have been basically the same: universal and free public services—health, education and social security—, subsidized goods and services such as public transportation and the basic food basket, and access to employment in the state sector, but with insufficient wages to cover basic needs, after the 1990s. With few exceptions, these are centralized, generic and egalitarian policies, mainly financed by fiscal mechanisms for income redistribution, in which the taxes paid by the private and cooperative sector of the economy play a growing role.

The government’s to and fro with the private and cooperative sectors since 2010, despite their validation as part of the socialist system, has become a source of controversy, delays in the implementation of approved policies, disenchantment for those who have opted for cooperatives and insecurity for those who want to start businesses. As a consequence, we have had to pay a high economic, social, and individual price―by not reaching the potential for income and well-paying jobs―of disenchantment and frustration “waiting for Godot,” who never seems to arrive.

Unquestionably, it is required that the state sector take the lead of the economy in strategic sectors and that it be governed by planning at different territorial and sectoral levels. But that does not exempt us from carrying out the necessary expansion of the non-state sector (cooperative, associative and private) and recognizing the legal existence of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

As Julio Carranza maintains, “first because they generate a large amount of employment that the state sector cannot retain if it intends to be efficient; second, because they guarantee certain productions and services that can contribute significantly to the growth of the economy and that, as historical evidence has shown, the state sector cannot carry them out efficiently; and third, because it allows mobilizing internal capital (savings) and external capital (remittances), which would otherwise be inactive or would not reach the country.” It would be necessary to add a better use of endogenous (family and community) resources, the potential of public-private partnerships and the ability to insert and contribute to local development strategies.

COVID-19 and its sectoral impact

And then arrived the double pandemic of COVID-19 and the intensification of the U.S. blockade. The associated economic crisis evidenced and further deepened social inequalities. Given the difficulties with food distribution, those with greater economic reserves can buy more and even hoard, while those who stand on lines and resell what they buy at higher prices have multiplied due to the shortage.

Remittances, diminished by the new restrictions and the fall of the economy in the countries where family members reside, ease the burden on some and not on others. Private vehicle owners move without restriction, but those who rely on public transportation are limited. Internet access and the income to pay for it determine virtual purchasing possibilities, market knowledge and access to information. The state of homes and the habitat determine the possibilities of self-care, the use of free time and even the use of the students’ classes on television. Rural-urban gaps and between rural territories have widened.2 At one extreme would be the most productive and profitable, where the population has achieved increases in family income, while at the other extreme are the laggards, who need help.

The health crisis caused by COVID-19 has had widespread impact on all sectors. In general, the degree of economic, job and life insecurity has increased. Although the government’s management has been successful, Cuba does not escape that reality. Cubans, entrepreneurs and workers, have felt that impact in the danger that threatens their lives, their families, their jobs and their enterprises, even if the situation does not affect everyone equally.

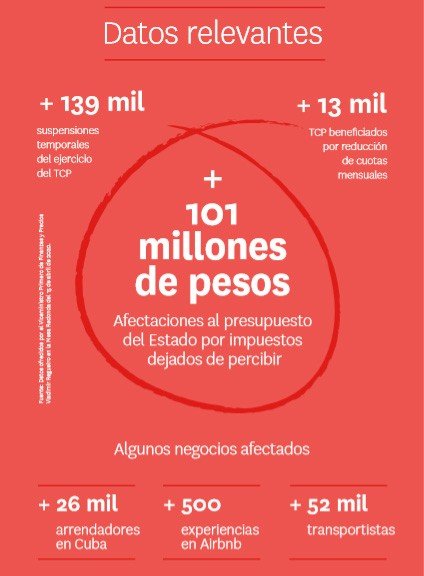

The current crisis has had a great impact on the still emerging Cuban private sector, with just a decade of existence. More than 139,000 temporary suspensions have been requested, 22% of the country’s approximately 605,000 self-employed (SE). The effects of the pandemic have hurt more than 26,000 landlords, more than 500 Airbnb experiences, and more than 52,000 carriers. Some 13,000 private workers have benefited from lower monthly fees, while the country has stopped receiving around 101 million in taxes.3

*Caption:

Relevant data

+139,000 temporary suspension of SE

+13,000 benefited SE through reduction of monthly fees

+ 101 million pesos Damage to State budget due to taxes not received

Some affected businesses

+26,000 landlords in Cuba

+500 experiences in Airbnb

+ 52,000 carriers

Added to all of this are people who, linked to the private sector, are not officially hired and jump into a kind of informality. According to some research, black people and people from “opaque” or disadvantaged territories are overrepresented in lower income groups.

Cuban Minister of Economy and Planning Alejandro Gil said that “it is about guaranteeing the vitality of the country, feeding the population and that the economic impact be absorbed at the least possible social cost; that we distribute this burden among all Cubans in order to get ahead.”

How to comply with the existing redistribution mechanisms? What role can the economic, private, cooperative and state actors themselves play to “distribute the burden” but, above all, to “guarantee the country’s vitality”?

As Pedro Monreal puts it, “during the eventual economic recovery, an equitable approach should be prioritized, that is, recognizing that social inequality needs differentiated actions in order to be able to promote results with social justice…. It is not a matter of distributing ‘evenly,’ but rather in a differentiated way. Social groups in situations of inequality―of any kind―should receive more benefits than others. Otherwise the causes that originate the inequality are not compensated.”

But the aspiration cannot only be to distribute public income better and more equitably and help needier individuals and social groups. It is above all about putting everyone to work based on the country’s economic recovery and relaunching the project of socialist construction, resuming the course of updating the economic and social model.

The social and solidarity economy gains validity

The ethics of behavior in socialism is cooperation to transform human and natural nature, for the sake of improving the lives of all persons.

The distributive ethics of socialism is equal opportunity for all. The “lottery” of individual, family, community and territorial resources should not determine the benefits and damage in people’s lives. Equal opportunities means compensating those harmed in the “lottery” through education and training and the promotion of entrepreneurship, in addition to direct assistance.

Ownership relations in socialism must be aimed at ensuring equality of opportunity, in the context of a mixed economy of socialism with market, and reflect the ethics of cooperative behavior.

It is here where we can find the utility of appealing to the Social and Solidarity Economy (ESS). These are forms of economic activity that prioritize social and environmental goals and involve producers, workers, consumers and citizens who act collectively and in solidarity. It covers the socialist state-owned company, foreign-capital joint ventures, cooperatives, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and private workers. It is geared at the constitution of different social relations, based on horizontality and cooperation, decent working conditions, the equitable distribution of earnings and the values of solidarity and responsibility. These elements build an economy whose core is not the reproduction of capital, but the centrality of work in the reproduction of life.

Cuban socialism has historically been social and solidary. The raison d’être of the socialist economy is to satisfy the material needs of society and support the transformation process, not to generate profits for its owners. The strategic objective of the model, as defined by the Conceptualization, is to promote and consolidate the construction of a prosperous and economically, socially and environmentally sustainable socialist society, committed to strengthening the ethical, cultural and political values forged by the Revolution, in a sovereign, independent, socialist, democratic, prosperous and sustainable country.4

How has the social economy in Cuba been conceived so far? Essentially promoted by the central government, “from the top down” and with a strong predominance of the state sector. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is implicit and naturalized, but exercised without corporate autonomy, in response to “guidelines from the top.”

Now, with a country much more diverse in forms of ownership and management, it is about promoting an economy made up of the whole of state and private economic actors, who explicitly assume and as part of their economic management of production, distribution and consumption of goods and services, the principles of responsibility to society―family, workers, customers and other actors involved in entrepreneurship and the community―and to the natural and built environment (heritage), in the interest of building a prosperous, democratic and sustainable socialism.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) refers to a set of social and environmental activities carried out by enterprises beyond the obligations of the law. This encompasses not only large enterprises―in our case, state-owned―but also SMEs, cooperatives and solidarity ventures.

CSR contributes to solving social and environmental problems. It can reduce the financial/regulatory burden on the State, adopting functions that until now have only been carried out by the public sector. Therefore, it constitutes a key piece for the creation of supply chains that lead to inclusive markets.

In Cuba, the CSR of enterprises of all kinds not only contributes to solving problems and meeting needs, but also fosters socialist values in its workers, managers and owners. Especially when public-private alliances are forged, which help to articulate the different forms of ownership based on local development.

(To be continued)

Notes

- Communist Party of Cuba (2011) Guidelines for the Economic and Social Policy of the Party and the Revolution 2011-2015; (2016) Guidelines for the Economic and Social Policy of the Party and the Revolution 2016-2020; (2016) Conceptualization of the Cuban Social and Economic Model of Socialist Development; (2016) Project for National Plan for Economic and Social Development until 2030. National Assembly of People’s Power (2019) Constitution of the Republic of Cuba.

- Luisa Íñiguez Rojas, Edgar Figueroa Fernández and Enrique Frómeta Sánchez (2019). “La heterogeneidad territorial en las actuales estrategias de desarrollo rural en Cuba,” Temas 98: 56-64, April-June 2019.

- Data provided by First Deputy Minister of Finance and Prices Vladimir Regueiro, quoted by AUGE, Privados del turismo.

- Communist Party of Cuba (2016). Conceptualización del Modelo Económico y Social Cubano de Desarrollo Socialista, art. 49, p. 6.