It’s not every day that you get to meet a figure of the century. Much less so if it’s an aviation luminary like Amelia Earhart. With a captivating and inspiring personality, the woman born and raised on the banks of the Missouri River in Atchison, Kansas, expanded the boundaries of what was humanly possible, breaking a dozen records — for speed and altitude — in the air and many barriers for women on the ground.

By the 1920s, aviation was beginning to take off. Hence Amelita, who developed her passion for adventure from an early age, faced the immense challenge of convincing a skeptical public that women could and should fly. “I hope men and women achieve their goals on an equal footing,” she said in her role as a pioneering feminist.

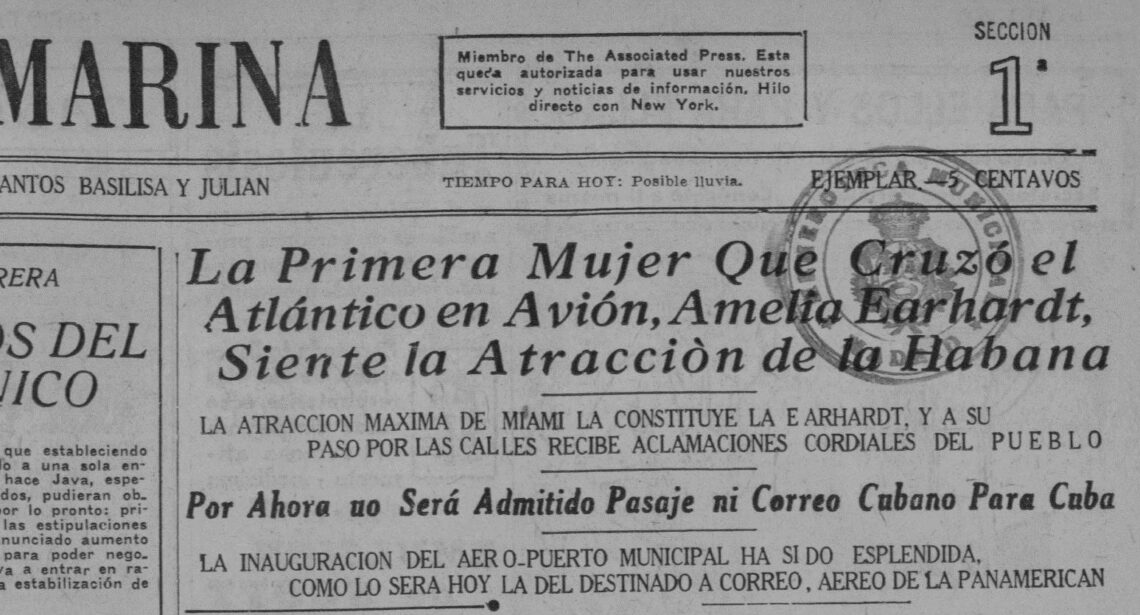

She was a bold and indomitable woman who spoke about mechanics and airplanes; she shone in a male environment, knew no obstacles, broke conventions, and set horizons for herself that no one had achieved, not men, much less women. Lady Lindy — she had been baptized with the female equivalent of Charles Lindbergh himself — spent a few hours in Havana, and was received here as if she had “landed on the moon.”

In style

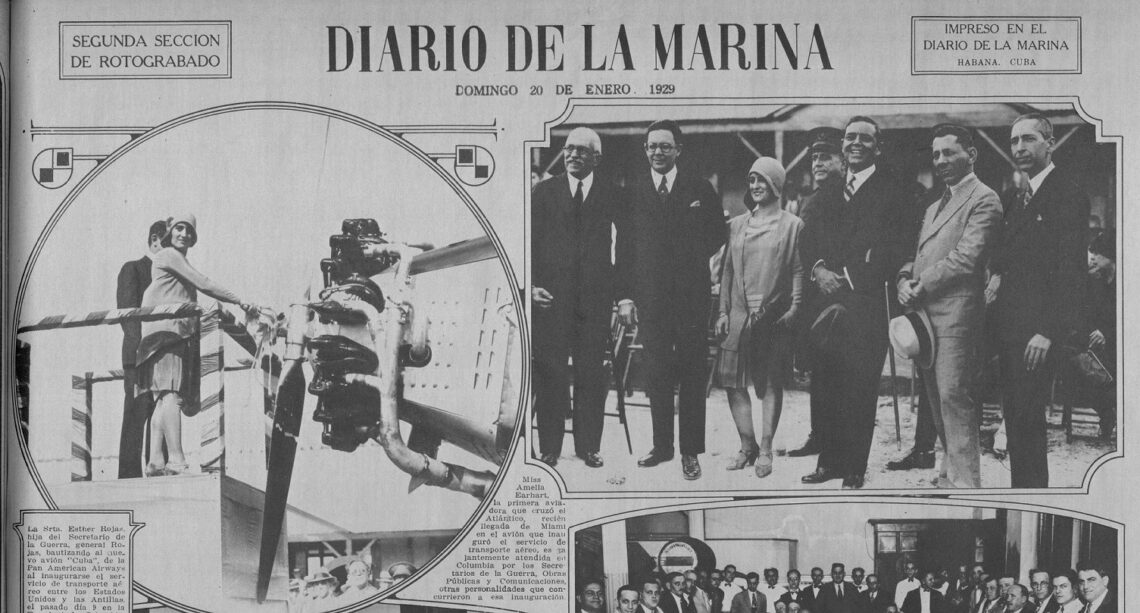

Under an auspicious sky, at around eleven o’clock in the morning on January 9, 1929, a twelve-seat Fokker F-10 trimotor aircraft was spotted, looking imposing among the clouds, preparing to land swiftly at Columbia Airfield. The atmosphere was charged with anticipation and a murmur began to fill the air. It was the beginning of something impressive.

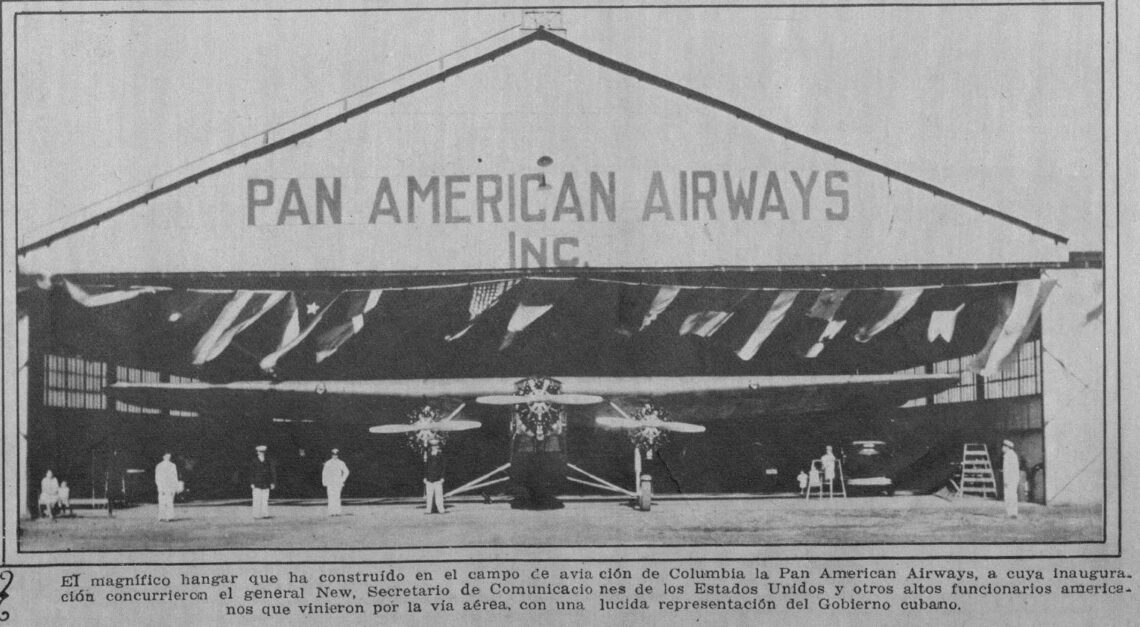

“Havana will soon be the hub of the world’s largest air route. An airline will connect the twenty-one nations of the Americas over 13,000 miles. The initiative for this work of civilization and progress falls to Pan American Airways,” the Diario de la Marina announced on the eve.

That day, on a flight that departed from Miami International Airport to Havana, and that would later have stops in Camagüey, Santiago de Cuba, Port-au-Prince (Haiti) and Santo Domingo, before arriving at its final destination, San Juan (Puerto Rico), the inaugural date of the Antilles Airline was encapsulated. It was a combination of long-haul routes coordinated by Pan American — which had already been flying to Cuba for fifteen months — which followed two days later with a new flight to Panama and would grow exponentially southward in the following months.

At that time, the goal was already to reduce travel times and distances were measured in hours and minutes instead of miles or kilometers. This air option reduced the average thirteen-hour time to Havana by ship to just a two- hour flight. Two planes served the route: the first took off from Miami at eight in the morning and landed in Havana at 10:15, while a second departed at 9:15 and arrived at 11:30. They returned to their base in Florida at 11:15 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Tickets, which cost $55, could be purchased at the corporate office at 13 Prado Street. Considered the maritime key to the Gulf, Cuba was also becoming the key to the skies of South America.

The military camp’s airfield was packed with hundreds of guests eager to witness history in the making. Among the authorities present were General Rojas, Secretary of War and Navy; Sánchez Aballí, Secretary of Communications; Carlos Miguel de Céspedes, Secretary of Public Works; and Colonel Sanguily, Chief of Air Force. Grant Mason, Pan Am’s manager in Cuba, along with several officials and technicians, gallantly attended to the crowd, while the Sixth District music band livened up the atmosphere. To close the event, five fifteen-minute flyovers would be conducted so that select guests could admire the capital’s progress from above.

Ambassador of the air

Amelia Earhart arrived in Havana aboard the Christopher Columbus, Pan American’s flagship, escorted in the air by Cuban military pilots Captains Martull and Laborde. In a masterful publicity stunt, the company’s president, Juan Trippe, saw her as the “ideal girl” to promote his new expansion, so he offered her an exclusive seat on the passenger list.

The entourage included General Harry S. New, Director General of the United States Post Office; William McCracken, Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aviation; Colonel Hambleton, vice president of the transatlantic airline; postal officials, businessmen and journalists. Eight airplanes of different models — including two Fokkers, two Lockheed Vega monoplanes, and a Sikorsky amphibian that carried only mail — formed the fleet participating in that inaugural voyage.

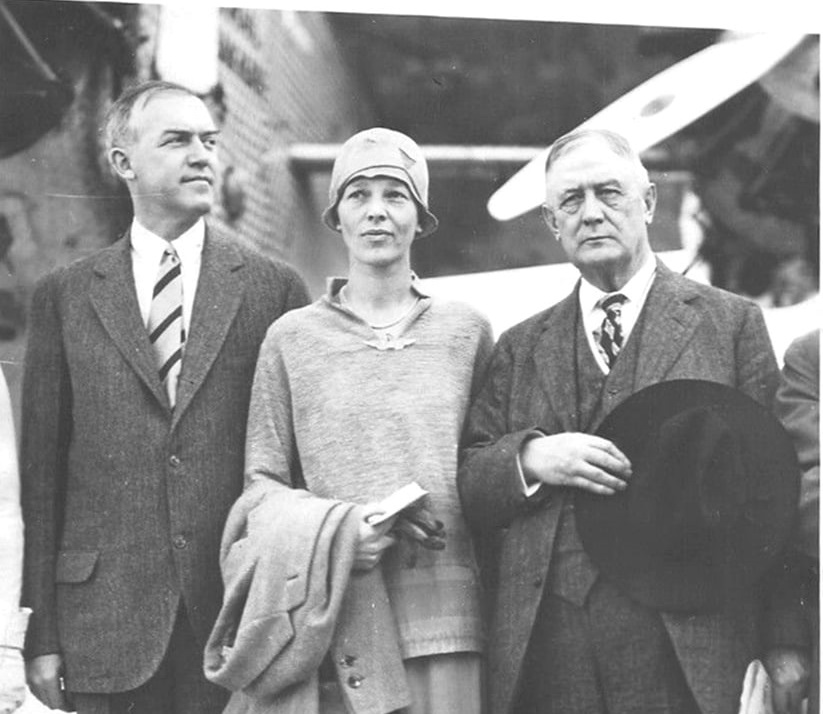

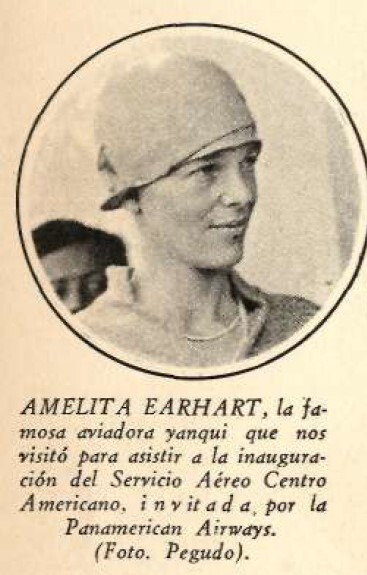

When the slender figure of Amelia Earhart appeared at the cockpit door, the spectators erupted in applause and cheers. The tropical sun bathed her face in gold as, with a shy smile, she friendly shook hands with everyone who approached to greet her. She wore a beige suit and, over her short blond hair, a small hat that matched her suit. A coat hung over her arm and two golden wings gleamed on her chest.

The Cuba, a Ford with three Wasp engines and comfort for twelve passengers, was immediately taken out of the hangar. Under the command of Captain Swinson, another American aviation ace, this was the plane designated to fly the Havana-Santiago route three times a week, with a stopover in Camagüey.

A small ladder was placed in front of the nose engine, serving as a platform, onto which, as usual, the godparents climbed: Dr. Carlos Miguel de Céspedes and Miss Esther Rojas, daughter of the Secretary of War. She pulled a cord and a bottle of champagne wrapped in a blue bag broke with a muffled noise on the metal frame, christening the brand-new aircraft.

Minister Céspedes welcomed the foreign delegation and gave the official speech. He then asked the star guest to come up to the platform and address the audience.

Moved, Amelita began by sharing her sorrow at not knowing Spanish to express her gratitude in that language for such a warm welcome. She confessed that the Cubans’ welcome had reminded her of the feelings she had experienced in June 1928, when she landed in South Wales and the crowd rushed to glorify her as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic; although she always made it clear that she was not at the controls of the Friendship.

The famous pilot also extended her fairy godmother touch to Cuba, evoking in her speech “the connection between both peoples, now united because on two previous occasions they have fought together for freedom.” She also praised the fact that, with the opening of the air route between Cuba and the United States, a leap forward had been made to contribute in various ways to the progress and unity of the Americas as a whole.

“I’ll fly back”

At the end of the air parade, the event’s organizing committee gave the young legend of the skies a special luncheon in her honor. She was accompanied by Cuban and U.S. authorities who had gathered at the Columbia grounds.

With a bouquet of flowers in her hand and pleased after so many courtesies, around three in the afternoon Amelia Earhart was ready for the return trip home. While waiting, she was talking with her childhood friend Mary Johnson when a reporter from Diario de la Marina approached her to find out about her impressions of her brief stay in Cuba.

“Miss Earhart, have you been able to confirm that Havana is a wonderful city?”

“I have confirmed it,” she replied with her luminous, courteous smile, “although not as fully as I would have liked. I only had time to see it from above upon my arrival. Later, on the way to the hotel where I had the pleasure of being greeted, I was able to admire part of the most beautiful place in the world and the best place to live. Once in the city, I marveled at the avenue built along the sea, the buildings and the promenades. I wish I could stay a few days, but that’s impossible; I have to return to Miami right now.”

“Will you come back?”

“Surely, and I’ll fly back. Maybe soon. I want to see Havana up close and have time to capture it all. I thought about flying to Puerto Rico and, on the way, seeing your countryside. I love Cuba’s eternal springtime and I like the affable nature of your people, who have welcomed me with cordial enthusiasm, something I will never forget.”

She was a woman of commitment. And although life and time prevented her from fulfilling her promise to return to Cuba, those four hours she spent in Havana were enough to engrave her glorious name in the nation’s memory.

She still had history to write in the air derby. She continued flying and earning social respect. In 1932, she crossed the Atlantic solo and secured a leading place in the annals of aviation. She gave lectures on the growing role of women and their universal rights, wrote articles in magazines, and founded the Ninety-Nines organization of women pilots. She married publisher George Palmer Putnam and her prenuptial letter is memorable, in which, above all, she bluntly defended her freedom: “Let us avoid interfering with each other’s work or pleasure, and let us not allow the world to witness our joys or disagreements. Perhaps I shall be forced to maintain a place where I can go to be myself, from time to time.”

Born with wings to fly, she had in mind something high-profile and much more challenging: a 27,000-mile journey that would take her across five continents. She wanted to circumnavigate the world aboard her Lockheed Electra and ended up disappearing somewhere in the Pacific Ocean in July 1937. She was about to turn 40. Amelia Earhart, her navigator Fred Noonan and the plane were never seen again. Her end, as tragic as it was epic, remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the century.