There is nothing more intoxicating than drinking history in one gulp. Scenes, passages, and names are claimed as the abrasive sap of cane liquor, lemon juice, and honey slide down the throat. One sip is hurried, two… pause to let the liquid rest. After the initial fury, it is understood that things that are worth it are worth enjoying calmly.

Hundreds of people come to the La Canchánchara tavern, a must-see in the historic center of Trinidad, a legendary city between the sea and the mountains, to experience a sensory journey. This cocktail, which emerged in the 19th-century countryside in eastern Cuba, had among its properties that of relieving respiratory congestion, maintaining body temperature, and being a nutritional stimulant.

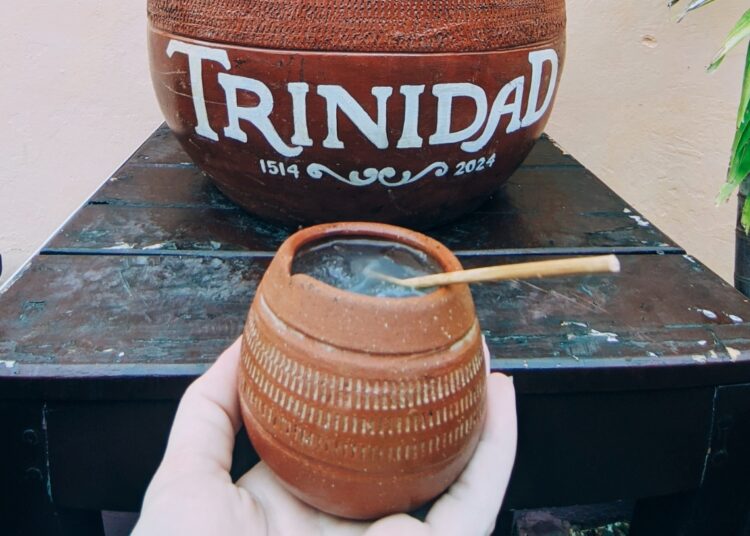

The Mambí independence fighters, it is said, drank it hot in gourds to “get into tune.” Centuries later, in the former residence of the wealthy Nicolás Pablo Vélez, the canchánchara is served in a small clay bowl, a distinctive element of the pottery heritage of the old township, personified in the Santander family. In a free and modern version, ice was added to the original components to mitigate the effects of the Cuban heat.

The crystalline amber, dense at the bottom, aromatic concoction is stirred. The mouthful, which seems soft but is only deceptive, torrid despite the coldness that the ice cubes give it, contrasts with the acidity of the citrus and subtly balances the earthy aftertaste of the honey. It is a feast of nuances. It is an intense, simple, sweet, powerful journey; the exquisiteness of a drink that has passed on for generations the living essence of its ingredients, without ever revealing the whole secret.

Rebel mix

Defining exactly when our ancestors entered the beverage laboratory is a high-grade adventure; as much as citing, from the mist of myth, among the alchemist pioneers the pirate Francis Drake himself sipping a mojito in front of the bay of Havana.

Cuba is a nation of all kinds of mixtures. It is stated that in terms of cocktails, it has been the birthplace of a vast menu. More than 450 recipes, suggests the journalist Ciro Bianchi in his article De fiesta por año nuevo. Bianchi clarifies that at least that is the number filed in the computer of the Floridita, the cathedral of our bars, the most internationally accredited by the everlasting Hemingway leaning against the large mahogany bar and the halo of its star bartender, Constante Ribalagua, inventing drinks like a magician to delight the most legendary figures.

The world has also savored the charms of this island in a bottle of Bacardi or Havana Club. When talking about the great Cuban cocktails, we usually mention the saoco, the mulata, the Mary Pickford, the presidente, the mojito, the Cuba libre, and, of course, the daiquiri, according to connoisseurs the king of them all. Those, among those with a pedigree. Because in the mouths of those having a few drinks on the corners, the most conspicuous have been the chiva prieta, bone’etigre, chispetrén, azuquín, mafuco, chinchirinchi, bájate-el-blumer, espérame-en-el-suelo and so on, in an inexhaustible catalog of formulas only suitable for true “glass-munchers.” Good rum does not flow like a stream through the street arteries.

Something similar happened in colonial times when the vicissitudes and logical hardships associated with the armed conflict and the nomadism of the scrubland prevented the creation of drinks as refined as those produced by bartenders inspired and favored by the abundance of products in their bars. Such deprivations formed a kind of “cocktail shaker” for the improvisation of amalgams that varied in concept, name and complexity according to what was added.

Among those most deeply rooted in the rebel palate were aguamona, frucanga, sambumbia, ponche mambí and canchánchara itself. Of course, a cocktail is endorsed by time and the particularly wise taste of the drinkers. That is why some evaporate in the cup of oblivion or, even when they are remembered, are not consumed; while others become popular and rise, effervescent, to “cheers!” in bars where you drink without thirst.

“During the period of the independence wars (1868-1898) the eating habits and customs of the island, until then of very little variation in the fields and cities, were altered. The war itself, with a marked impact on the economic, social and political transformations, caused these and other aspects of the material and spiritual culture to be modified since October 10, 1868. Necessarily, Cubans’ primitive diets are revitalized and the conciliation ― and in others the fusion ― of the different uses and customs that are practiced in the complex Cuban society of centuries ago is spontaneously created. There are also other novel and enriching results that add to and modify culinary habits.”

With this outline, Santiago de Cuba researcher Ismael Sarmiento Ramírez condenses the context of survival in extreme conditions and in the midst of the already devastated ecological environment that led, among so many innovations, to the apogee of authentic Mambí gastronomy.

In his encyclopedic book Cuba. La necesidad aguza el ingenio, the author ― currently a professor of Modern History at the University of Oviedo, Spain ― proposes through five chapters in 400 pages an x-ray of the Liberation Army’s subsistence regime, its rudimentary weapons, its food, its medicines, its clothing and utensils. Due to the size and rigor of the study, the exuberance of images, in some cases unpublished, the innovative approach and the extraordinary quality of the print result in an impressive work.

James O’Kelly, the daring Irish correspondent for the New York Herald who crossed rebel lines at the end of 1872 to interview President Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, explains in his well-known story Mambí Territory: “The common drinks in free Cuba are the aguamona and ginger. The first consists simply of hot water sweetened with honey. The last one is the Mambí punch and it is made by adding the ginger root to the aguamona.” Regarding this, he notes that “it was a very refreshing drink and not a bad substitute for whiskey-punch; having the advantage of not producing intoxication and acting as a stimulant.”

Agua de mona or aguamona — for some, a Cuban adaptation of the Spanish agualoja — was hot water in which honey or candied sugar cane was diluted, and in its happiest version it could admit citrus leaves. But if there were too many hungry people in the camp, then the Agua de mona turned into rabona, because it had to be stretched by adding even more water so that there was at least one sip for everyone. Ramón Roa tells in A pie y descalzo a funny anecdote about the practice of “baptism” that aimed for quantity without regard to quality: “As we left, a young and friendly guajira, draining a bottle of honey, offered to the exhausted American, little more than a thimbleful of the already exhausted liquor, telling him: “I won’t put a lot of water so it tastes better.” “No, miss,” the blonde Yankee replied, “put plenty of water in it because I want a lot of bad stuff more than a little good stuff.”

For demanding palates there was the frucanga, which had cane liquor, honey, ginger, sour orange leaves and chili guaguao. According to the social imagination, this “spicy mixture” stirred the insides in such a way that the current exploded through the edge of the machete in frantic charges.

Sambumbia was simply made with bee honey or cane syrup in water. Much water. The word has endured in the popular lexicon as a derogatory allusion to excessively soupy food or a tasteless drink. Colonel Fermín Valdés Domínguez evokes in his copious Diario de Soldado: “Serafin [Sánchez] always has a memory of the events of the men of the Revolution. Speaking today about [Juan Bautista] Spotorno, the autonomist and Spaniardized of today, he said that in the old war he heard people say: ‘They are right to call water with honey Cuba Libre, because in truth this war is a sambumbia.’”

It was precisely Cuba Libre — honey water with cane liquor and a few drops of lemon — that was the most universal in the scrubland recipe book, although over the years its origin would be distorted, reiterating that it was born at the beginning of the 20th century in some Havana tavern when an American officer mixed rum with cola (soda). It is easy to locate its appearance on the battlefield. Among many chroniclers, Félix Figueredo, doctor and brigadier of 1868, reveals that sick in a hut, he ate jutías and drank Cuba Libre.

“Through the consumption of all these spirituous beverages, the members of the Cuban Liberation Army try to obtain, although not all in moderation, the functional stimuli and nutrients that their weakened organisms require, and that under the conditions imposed by the circumstances of the moment, they can hardly find in other foods with the required regularity,” historian Ismael Sarmiento analyzes in his research. The most frugal snack, however ridiculous as it may seem, was an event for an empty and naked stomach.

The canchánchara in diaries and memoirs

In the so-called campaign literature, rich in details and a precious source for interpreting the interiorities of the libertarian feat, we find disparate references to the collection of “matahambre” potions and specifically to the canchánchara, a word whose etymological origin there is no mention of.

Nor are there as many references as one might imagine. Perhaps because at chow time the ingredients required for its preparation were not always fortunate enough to coincide; or perhaps because many leaders — Maceo and Gómez, for example — rejected the excessive use of alcoholic substances in their troops, even when the insurgent soldiers’ were especially fond of them.

In fact, in February 1870 the Military Organization Law stipulated the delivery — when circumstances permitted — of one ounce of liquor per capita. The cane liquor — which provided the distinctive touch in this case — could be obtained in raids on convoys and grocers, in artisanal mills within their prefectures or through clandestine barter.

José Martí, who with his careful gaze gives marvelous images of the eastern countryside, writes in his famous diary from Cap Haitien to Dos Ríos:

“And we are talking about lemon honey, which is the juice, very boiled, that cures tenacious ulcers.” While his friend Valdés Domínguez records about the visit to the Santa María de Rosario farm, Camagüey region: “In such houses is where the misery that the war leaves, as a sad sequel, in its path is palpable. Guzmán, the Lieutenant Governor, a couple and us and my assistant José, arrived at the house. We dismounted and those good Cuban women offered us guanine coffee, canchánchara and delicious bell honey. Guanine coffee is a bitter brew that I don’t like, I preferred the canchánchara which was very tasty.”

Lieutenant Colonel Eduardo Rosell y Malpica, who died in February 1897, refers in his notes:

In many places, they give us coffee. When this is missing, they make us Canchánchara, Sambumbia or Cuba Libre. These are three similar things; the first is made with honey and sugar, boiling it first alone, and then doing it again, with water.

Likewise, Commander Manuel Arbelo describes in his Memoirs of the last war for Cuban independence:

We saw a large tree, although with clear foliage, and at its foot, Captain Plasencia’s hut, where he was at that moment drinking in a gourd the steaming and fragrant canchánchara that constituted the breakfast of the Cuban patriots.

Raúl de Acosta makes a similar mention in La Revolución en Camagüey: “We headed, as was usually customary, to the pavilion of General Lope Recio, to drink the well-known canchánchara.” For his part, Horacio Ferrer narrates in Con el rifle al hombro that “Our men were going to surprise them there, in search of honey to make canchánchara and wax to make matches.”

Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, a general with a fruitful career, explains in his Memoirs of the War: “Upon our arrival, a pretty young woman presented him with a cup of coffee and then offered others to the General Staff and the officers present, while the Prefect increased his activities preparing lunch and canchánchara for everyone.”

Another who mentions it in a line is Manuel Piedra Martell, in Mis primeros treinta años: “My invitation [to have breakfast], as expected, was accepted with joy. I called Claudio [the assistant] and ordered him to make ‘canchánchara’ for everyone.”

In the field of fiction, the term also emerges. “After seeing everything, shaking hands with the wounded from Saratoga, expressing my wishes that they would get better soon, drinking canchánchara from a gourd, which was distributed to patients who could not drink milk…,” Carlos Loveira’s Generales and Doctors recreated.

The Biography of a Runaway Slave, by the ethnologist and writer Miguel Barnet, attests:

One of the best remedies for health is honey. That was easy to get in the mountains. There was of the earth everywhere. I found it very abundant in the woods of the mountains, in the hollow júcaros or in the guasimas. Honey was used to make canchánchara. The canchánchara was a very tasty water. It was made with river water and honey. It was best to drink it fresh. That water was healthier than any medicine today; it was natural.

The ideal vessel to serve the canchánchara, as well as the rest of the drinks seasoned with fruits, herbs, roots and other things, was the gourd. It was usually made with coconut, totuma or the immortal güira, as they were resources that were within reach in the wild fields. The Mambí ingenuity produced a peculiar “set of dishes” made of shells. Martí confirms it when he crosses the pure mountain towards Arroyo Hondo: “we passed through a forest of green jigüeras attached to the bare trunk or the sparse branch. People are emptying the jigüeras and trimming them.”

Sweet tradition

A sublime elixir due to its simplicity and flavor, the canchánchara has transcended to the present day as an attractive exponent of national cocktails. Now it is more associated with the city of Trinidad, not only because of the tavern that has appropriated its renown and attracts like a magnet gasping tourists driven to taste the qualities of this curious, pleasant, indigenously Cuban drink; but because since the beginning of the 1980s, during the revitalization of the image of the township, today a World Heritage Site, specialists in heritage management restored the old house marked with the number 90 on Calle Real de Jigüe, to promote the idea of rescuing the drink that had managed to survive thanks to oral tradition.

Without a doubt, the place has a nice bohemian atmosphere and is often full of guests. Foreigners don’t get drunk with the canchánchara, but their tongues get tangled when they want to pronounce the word. Some buy the pot-bellied bowl in which it is taken, as a souvenir. As a promotional motto, it is stated that the stay in Trinidad would not be complete if one does not try the canchánchara.

As a result of the consolidation of a well-founded and better-directed project, the Mambí drink has been acquiring even greater prestige since the first edition of the festival with its name was held in December 2023. Among its novelties was the preparation of a colossal canchánchara of more than 250 liters, which sought to be registered in the Guinness Book of Records. “Canchánchara, tradition and culture,” in turn a unique combination of history and public entertainment, is emerging as a key event in Cuba’s artistic and tourist calendar.

Of course, there are other regions further away from the media spotlight where, despite acute shortages, attempts are made to perpetuate the presence of the canchánchara as part of local traditions. This is the case of the Huellas del Batey Community Project, in the Holguín town of Santa Lucía, where the original recipe without ice is defended, because it is of “Mambí lineage.”

Also in the Oscar María de Rojas Museum, in Cárdenas, the ritual of offering it during Culture Week or certain patriotic commemorations is preserved. Surely there will be other places or similar efforts in the national geography where, due to identity or necessity, this bush cocktail continues to be toasted.

The contemporary recipe is as follows:

Ingredients

15 ml bee honey

15 ml lemon juice

45 ml of cane liquor (if not, use rum)

30 ml of water

Ice cubes

Preparation: pour the honey and lemon juice into the container. Stir to dilute the honey. Add the cane liquor, ice, complete with water. Stir again. If wanted, you can strain it or decorate it with a slice and…. Let’s have a “canchancharazo”!