The massive influx of Chinese to Cuba occurred between 1847 and 1874, when some 150,000 were brought to the island to work on the sugar plantations, in semi-slavery conditions. But the migratory flow continued during the first half of the 20th century, sometimes coming from the United States, legally, but also clandestinely.

At the beginning of the Republican era, in 1902, they fought to gain a place in the activities dedicated to commerce, in which the Spanish had primacy. They made their way, accumulating capital as sellers of vegetables and fruits, until they became popular figures in everyday life. The writer Renée Méndez Capote, in her book Memorias de una cubanita que nació con el siglo, remembered them as:

“Those Chinese greengrocers, loaded with up to six baskets that hung in two groups of three, one on top of the other, at the ends of their long pole. They would bend down at the doors of houses, taking out their merchandise with a patience, a joyful sweetness that was enchanting; those slight figures, almost without exception, came from Canton, with their peculiar shoes, black, like fine espadrilles with leather soles, with their specially cut suits almost invariably made of blue cotton, I say almost because I think I remember them also dressed in grey, with the pointed round straw hat under which they wore their incredibly long braid twisted in a big bun…The outskirts of Havana were full of small, well-cultivated vegetable gardens. The countryside appeared to be strewn with Chinese people squatting, covered by little round hats. At the door of their little houses the most primitive farming tools: they watered their land with a watering can and cut the grass with sickles.”

The establishments of their fellow countrymen in the city and also the street vendors were supplied from these small vegetable gardens. The practice continued for half a century.

The writer and journalist Gerardo del Valle recounted in 1928: “They go with baskets on their shoulders, walking with a rhythmic step that mathematically helps them to get to the most remote suburbs. You can see them at seven in the morning, on a happy pilgrimage, along the Avenida de los Presidentes to Vedado. They know the needs of each client by heart and adapt to each complex character they encounter. Business is always done with them. Deeply human, they try to please and have the patience unique to the children of the yellow race of knowing how to wait when the client has a monetary crisis and needs a saving loan… There is no house in Havana that does not have its Chinese vegetable seller who solves the problem of the domestic economy.”

The Chinese inserted themselves into that universe dominated by the so-called street vendors who sold almost everything, although their presence was more discreet if we compare it with the Arabs and the Spanish.

In the case of the clothing merchants, Renée Méndez Capote recalled: “The Chinese silk merchant was a very different type, he dressed in raw drill, with a tie and wore a straw hat. I do not remember even one with a braid. They used long, polished nails and smelled of perfume. They arrived at the houses where they were welcomed in and, in the living room, with all the women around them, they opened their fragrant suitcases, full of fine and pretty things from China and rice powder and French perfumes, and socks and handkerchiefs made of linen and silk, embroidered house dresses, leather slippers for men and exquisitely embroidered ones for women.”

Spinach for pigweed

I found the anecdote curious. It was told by Dr. Enrique Bello in the article ““¿Señora, está usted segura que lo que come su niño es espinaca?” published in 1942, by Bohemia magazine.

In a Havana family, there was a debate about the excellent nutritional qualities of spinach and they wanted to incorporate it into their meals, especially for the benefit of the children in the house.

No one better than the Chinese Felipe, who had been supplying them with vegetables for 20 years, to find them the vegetable unknown to them and about which the press insisted on its health benefits. The lady asked him if he had spinach, “Like all the Chinese vegetable growers in Cuba, they do not understand well what is said to them when the language contains a word that is a bit difficult and, in addition, they are characterized by saying yes to everything they are asked and do not understand, always accompanying their affirmation with a kind smile, he answered: ‘Yes, I have it.”

And the lady then asked him to bring her a bunch of the vegetable every day.

“The poor Chinese man, not knowing the scientific role he plays in Cuban society, consulted his compatriots on the matter and, in accordance with the mentality of this race, which we love and respect so much in Cuba, he decided, so as not to mortify the lady, to bring her a bunch of pigweed since he knew that this plant is edible.”

As the child looked healthier, according to the mother, due to the frequent consumption of spinach, she did not fail to recommend to her friends that they incorporate the vegetable into their salads. The news spread “and poor Felipe, in the best of good faith, grew and grew, without ceasing, pigweed for his merchants.” Other countrymen followed his example, the demand was insatiable, all Cuban mothers, with the forgiveness of the grammarians, are ‘pigweeding’ their children and not ‘spinaching’ them.”

Diversity

At the beginning of the 1950s, the Chinese colony in the Cuban capital was still large. According to a feature article published by journalist Ángel Cuiña Fernández in Bohemia magazine, more than 10,000 Asians lived in the city and municipalities of Regla and Guanabacoa.

“These men deserve admiration for their love of work and perseverance. They are seen in both commercial and more rustic and arduous jobs, with many of them dedicated to agricultural work. There are also journalists, intellectuals, mechanical artists, etc.”

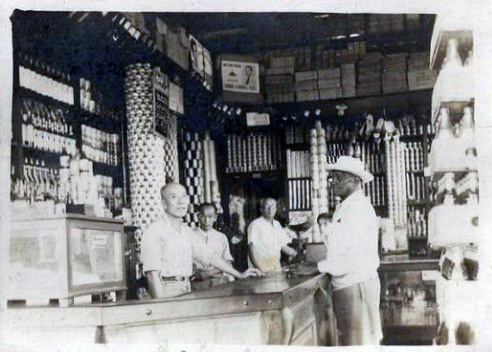

At that time, before dawn, the Chinese from Capdevila and Palatino, who harvested chard, cabbage, lettuce, watercress and other vegetables, would arrive at the stalls of their fellow countrymen in any Havana market. In addition to the classic neighborhood grocery store, laundries, fishmongers, chicken shops and eating places run by them proliferated.

“A laundry operated by Chinese, due to its laboriousness, is similar to a beehive. Its staff, however, despite the enormous heat that emanates from its lit stoves and the unbreathable atmosphere that invades them, work around twelve hours a day. From time to time, they stop to inhale, through the smoking rod that is used by the community, the aromatic smoke that the smoke produces. And so, between carrying and bringing large iron plates with which they smooth the clothes, they earn their living, really sweating a lot…,” Cuiña Fernández noted.

Chinese newspaper vendors were different from their Cuban colleagues because they did not vociferate in the streets of Havana or hang from trams and buses. They used to sit on a stool in front of some establishment in Chinatown, waiting for a buyer. In the meantime, they took advantage of the time to read the news for free.

The Chinese community published four newspapers and a magazine in the 20th century. The most enduring publication was Hoi Men Kong Po. It began to circulate on May 3, 1922 and stopped being printed in the 1970s.

Over time, the more successful merchants expanded their businesses. “The set of grocery stores, the luxurious restaurants, the set of silk shops, all set up in keeping with the times and attended by fine and accommodating personnel, are today places visited by buyers. Galiano, San Rafael, Neptuno, Paseo Martí and other important streets in our capital are home to top-notch Chinese consortiums,” said Cuiña Fernández.

The business in metal carts

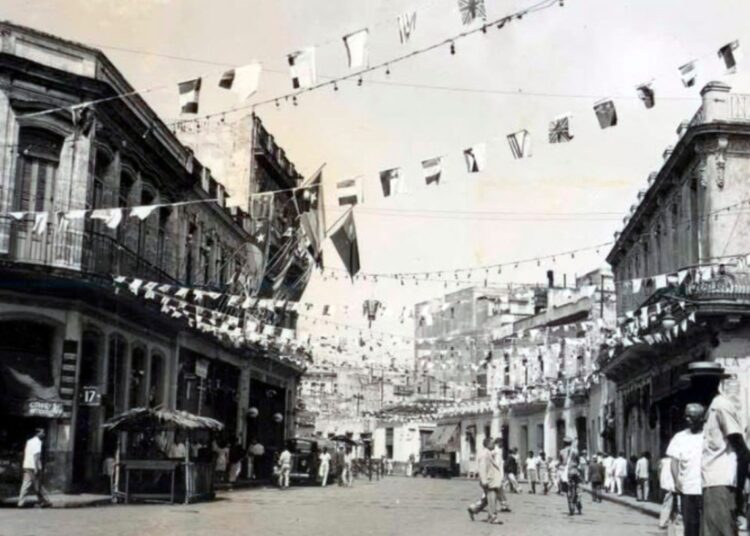

The increase in immigrants consolidated Havana’s so-called Chinatown, which currently extends from Escobar to Galeano and from San José to Reina streets, in the municipality of Centro Habana. There they created various businesses, especially establishments to sell food, very well received by the Cuban population.

The small eating places, Chinese food restaurants, expanded to different neighborhoods, and also the stands where they made pork rinds, fried plantain, potato or sweet potato chips, cod and malanga with parsley fritters and popcorn. In 1950, journalist Luis Rolando Cabrera wrote:

“There were stalls that expanded their menu and added other delicacies to the classic black-eyed bean rolls and fried pork rinds, which increased the number of customers. They sold yuca with mojo sauce and roast pork, serving a portion on a sheet of paper for two or three cents. The fork was rudimentary and very much in keeping with the Asian origin of the supplier: a toothpick.”

These stalls were visited by a regular clientele, newspaper sellers, lottery ticket sellers, poor people who, not having enough cents to pay for a couple of dishes at the restaurant, would approach the counter of the Chinese stall and buy, with less than 10 cents, a bit of yuca, another bit of pig entrails, three or four fried sweet potatoes and even have enough left over for a couple of bananas for dessert.”

The joke, the Cuban grace, was not lacking when it came to naming some of the foods. They called the fried plantains “mariquitas,” the elongated flour fritters “pitos de auxilio,” the ones made of black-eyed peas “bollitos” and the roast pork “comida de guapo.”

As the clientele dwindled, some Chinese moved the business in metal carts and went to sell in the neighborhoods. Their Cuban colleagues realized that the idea was good and also set up their own cheap restaurants on wheels, where you could buy hot dogs, steaks and the famous fritters. This was at the beginning, then they expanded the menu, both in the fixed and mobile stalls:

“And they added fish, tortillas, stuffed potatoes, chorizos and other things. There were merchants who soon established the ‘chain,’ like in the U.S. stores, and seeing a goldmine in the business, acquired a train of carts that they then rented out per night to the vendors. Others made ‘chains’ of shop windows and established them of a particular type in various neighborhoods of Havana,” narrated Luis Rolando Cabrera in his feature article “Del puesto de chinos a la carretilla aerodinámica.”

________________________________________

Sources consulted:

Renée Méndez Capote: Memorias de una cubanita que nació con el siglo, Huracán publishers, Havana, 1964.

Ángel Cuiña Fernández: “El chino, hombre de trabajo,” Bohemia magazine, January 22, 1950.

Luis Rolando Cabrera: “Del puesto de chinos a la carretilla aerodinámica,” Bohemia magazine, February 12, 1950.

Enrique Bello: “¿Señora, está Ud. segura que lo que come su niño es espinaca?” Bohemia magazine, October 25, 1942.

Gerardo del Valle: “Instantáneas callejeras,” Bohemia magazine, September 16, 1928.

https://chinosdecuba.blogspot.com/