In the same Caribbean from which Cuba emerges, in Puerto Rico, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio (Bad Bunny) was born in 1994. The twelve-time Latin Grammy nominee (2026) released the album Debí tirar más fotos (I Should Have Taken More Pictures) in January 2025.

The accompanying short documentary visually exposes the gentrification of Puerto Rico and the loss of identity caused by the migration of its people, the occupation of the territory by predatory tourism, the climate crisis and housing evictions.

Many residents no longer recognize themselves in these spaces and feel like “foreigners in their own homeland,” where they were born and “want to die,” as a Puerto Rican is heard saying in the documentary clip “Aquí vive gente” (People live here), the predecessor of Debí tirar más fotos.

Puerto Rico has lost approximately 2.4% of its population between 2020 and 2023, largely due to emigration. This is a considerably lower rate than the approximately 24% that Cuba has lost of its resident population in four years due to the mass emigration of its citizens. This exodus reflects the profound economic and social crisis we are experiencing.

Regarding the return to their country of Puerto Ricans who emigrated, recent data from the American Community Survey (ACS) indicates that, between 2018 and 2019, there was a net return of approximately 88,000 Puerto Ricans to the island, suggesting a partial recovery of the population after the mass exodus following the destructive Hurricane Maria in 2017.

However, for many Cubans — a diasporic group that tends to emigrate permanently when compared to other Latin American diasporas — the possibility of voluntarily returning to the country is almost immediately ruled out by the daily precariousness and hopelessness of the current social climate.

Under these circumstances, it is difficult to imagine the island as a safe haven or to consider returning as a reasonable decision.

But some do, and some have even decided to stay, trying to struggle for a decent life, to help build a future that many of us have decided not to wait for.

The three-quarters of the Cuban population that still remains in Cuba is one side of the kaleidoscope we hardly ever look at.

On the other hand, what we know about migrants who voluntarily repatriate in Cuba is merely anecdotal because there are no official figures: some return to open businesses or grow old in their lifelong homes.

However, we know that under current conditions, the outflow now far exceeds any recorded return, even in times of deportations from the United States.

“I Don’t Want to Leave Here”: an anthem to who we are

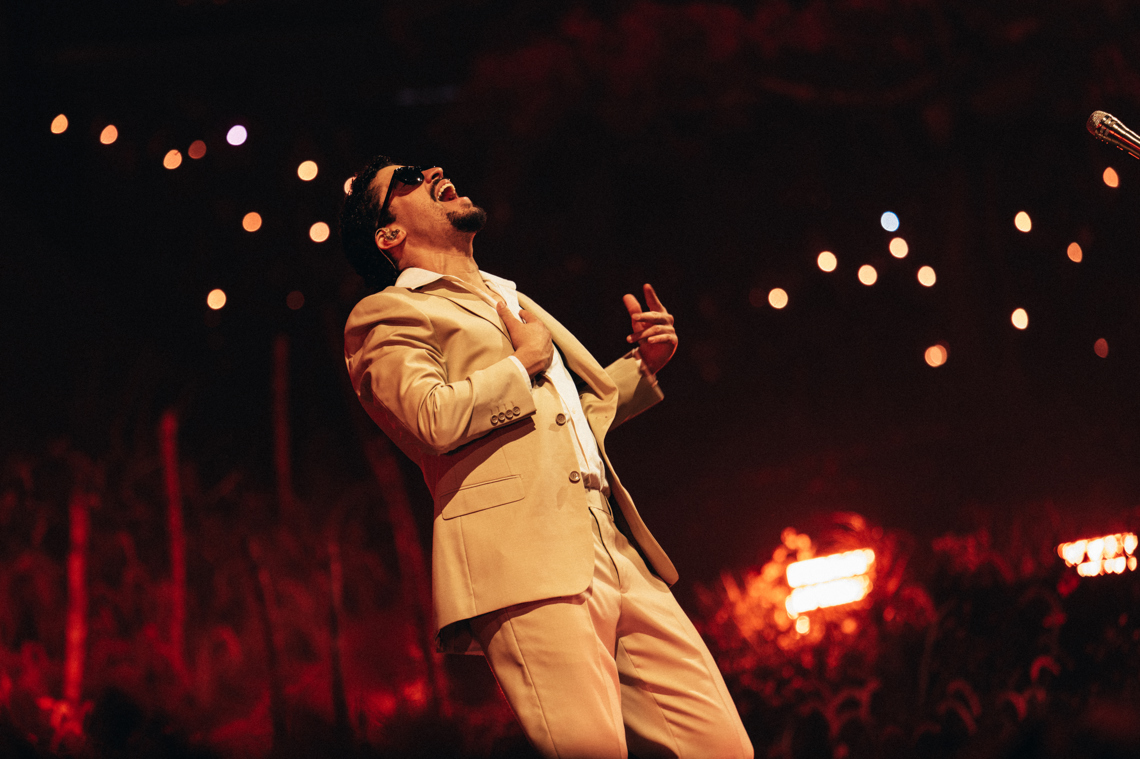

“I Don’t Want to Leave Here” is an emblematic title for a series of shows by an Afro-Latinx and diasporic pop artist like Bad Bunny. In addition to its box-office success, the “residency” managed to connect numerous Puerto Ricans in the diaspora with their homeland.

In my view, it launched some disruptive messages into the Latino migrant imagination, which also impacted us as Cubans: 1) the country of origin not only as a space of nostalgia, but as a present and a possibility for the future; 2) migration not as a definitive crossing, but as a circular movement, a coming and going; and 3) the right to remain and build a life in the destination country, in this case the United States — a right also sustained by a historical debt: for generations, Latin American migrants have sustained key sectors of that country’s economy, culture and daily life, and their contribution deserves recognition and gratitude — as an inseparable part of that migratory experience.

The static tour of Puerto Rico ended up constructing and narrating the country as a mosaic of culture and identities worth exploring. By establishing himself there, Benito transformed the periphery into the center.

Another emblematic fact is that he didn’t include the United States on the list of destinations for his international tour, “Debi tirar más fotos World Tour,” to avoid ICE raids among a significantly Latino audience, reinforcing his commitment to the safety and representation of the migrant community in that country, especially the undocumented.

In an interview, he explained: “There were many reasons why I didn’t perform in the United States, and none of them were out of hate; I’ve performed there many times.” He added: “All [of the shows] have been magnificent. I’ve enjoyed connecting with Latinos who have been living in the United States. But specifically, for a residency here in Puerto Rico, when we are an unincorporated territory of the United States….”

He also emphasized his concern for the safety of his audience: “People from the United States could come here to see the show. Latinos and Puerto Ricans from the United States could also travel here, or anywhere in the world. But there was the issue that the damn ICE could be outside [my concert]. That’s an issue we talked about and that worried us a lot.”

Bad Bunny’s recent work and stance show how even the most popular wave of culture can be a form of living resistance to the narratives that have presented us exclusively as peripheral territories, inferior cultures, or “third” in the world order. We’re here, and we’re not leaving.

Resisting to subvert

What we understand by country goes beyond its geographical boundaries: a country is built, lived and imagined.

This is something Bad Bunny has done, beyond getting his audience to dance. His visibility opened space for us to rethink the way we tell who we are and reminded us that, as a Commonwealth of the United States, Puerto Rico is not just a summer resort for gringos, but a place where “people still live,” with culture, customs and a life worth preserving and dignifying.

From my own experience, I know that my generation has disconnected from Cuba with the same anguish that Puerto Rican millennials — and so many other Latin American diasporas — have disconnected from theirs. Bad Bunny isn’t Cuban, but for many of us, it’s as if he were, because of everything his activism represents.

As Cubans, however scattered we may be, I wish we could once again invent our own fictions about what it means to be Cuban in a world saturated with narratives that try to push us aside, to the periphery.

We are a small island that has never gone unnoticed by the rest of the world. We cannot allow difference of opinions, polarization (a contemporary reinterpretation of radical positions like the one we saw during the rafters’ crisis, which serves us no purpose today) and political apathy to continue to fragment us and distance us from what we essentially are: a whole country. We must recognize the hidden mechanisms that are trying to make us disappear.

Nor can we, as a diaspora, those of us who are part of it, stop looking at the island with respect and reverence for those who have been brave enough to stay and build with their own hands a future that none of us who are outside were able to wait for.

They deserve our respect, those who struggle daily — some because they have no other way out — against blackouts, scarcity, apathy, the indifference of leaders, the lack of food and medicine, and yet they get up every morning to make a living however they can, to live it in the best way possible, because it’s the only way they have.

“People who have invested their life savings not in buying a plane ticket and moving to another country, but in starting a business, even in the sea of economic uncertainty that prevails on the island.

Bad Bunny’s “residency” made me think of something I thought was lost among Cubans, and I’m optimistic enough to believe it’s not entirely lost: the possibility of imagining our homeland not only as the past, but as the future; a place of return, symbolic but also real: of possible embraces, of reunion with our food, our music and our people.

In short, with that part of us that faded while learning to flourish in other lands and hardened with resentment toward hierarchies that have failed to represent us as a people.

I want to believe that we can still build with our own hands the crystalline horizon we sought when some of us left and others stayed. All of us, ultimately, are the Homeland.

But for that horizon to cease to be an illusion, our desire is not enough: we must break the intransigence of everyone; we must ensure that political decisions truly guarantee us the real right to return, to participate, to influence the country’s course. That we be allowed, without hesitation, to think about and help rebuild Cuba, both from without and within. Will it be possible?