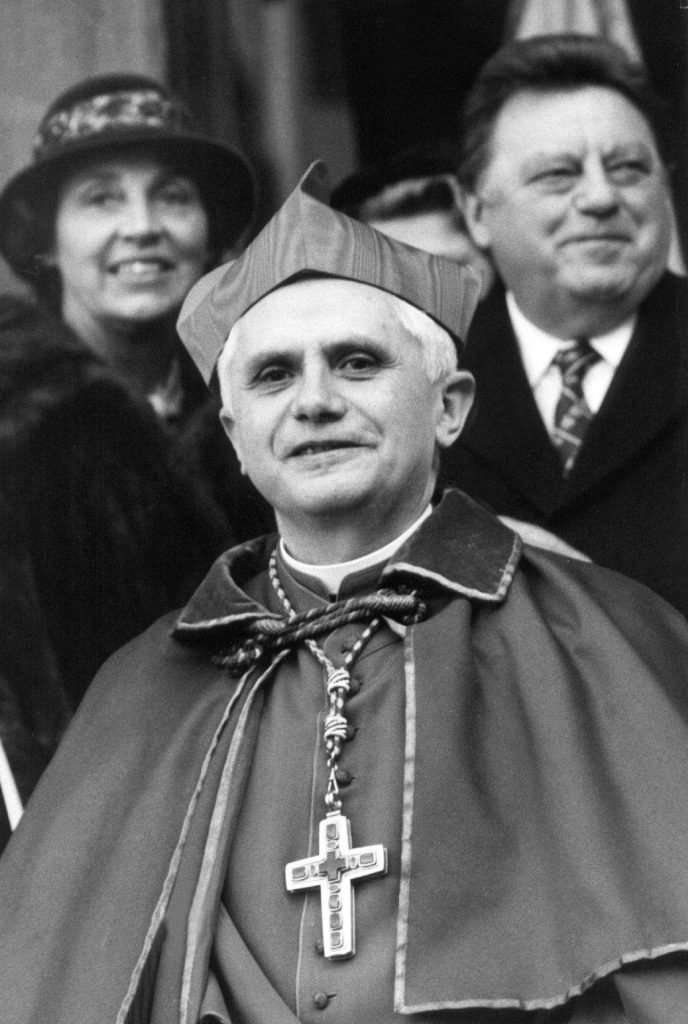

The German Joseph Ratzinger (Bavaria, April 16, 1927), who assumed the papacy under the name of Benedict XVI on the death of John Paul II, came to power after a theological-political path that began under the aggiornamiento of the Second Vatican Council, in which he stood out together with reformist theologians such as the Swiss Hans Küng (1928-2021) and the German Karl Rahner (1904-1984). In the end, changes in his socio-theological orientation and turns to the conservative side, especially after the events of May 1968 in Paris, made him stick his neck out against liberalism, atheism and Marxism.

In 1981, John Paul II placed him at the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, a name that designates the Inquisition established in 1542, at the height of the Renaissance, with the aim of defending the Church from heresies.

Ratzinger concentrated on detecting “non-acceptable doctrines” — that is, theologically and politically incorrect — until he ended up punishing, say, theologians like Küng himself and the Spanish Jon Sobrino (1934). In the first case, he removed him from his chair in Tübingen for having questioned the infallibility of the Pope; in the second, he forbade him from teaching and writing for “emphasizing the human side and forgetting the divine side of Jesus.” Without forgetting, of course, the trial against the Brazilian priest and theologian Leonardo Boff (1938), initially sentenced and suspended a divinis for his work within Liberation Theology.

Benedict XVI’s credentials did not contribute much to link him with the truth (the “Pope of Truth”). In any case, Ratzinger had his own, the same as that of the high conservative ecclesiastical hierarchy and that of institutions such as Opus Dei: monitor and punish the deviant, maintain that outside the Church there is no salvation, deny the right of women to control their own bodies, stigmatize homosexuals, condemn the condom as a contraceptive method and, in the Cuban case, delegitimize popular religions of African origin, despite constituting an essential part of national identity.

Under his leadership, the Catholic Church decided to protect humanity from certain annihilation. But it wasn’t about the arms race, or global warming, or hunger. He persecuted homosexuality and transsexuality, “self-destructive” alterities (a pronouncement not only consistent with the theological and social conservatism of the German prelate, but also with the heritage of the Polish Pope, a flagellator of sexual practices such as homosexuality and masturbation). As is known, the purpose of “saving humanity” is based on the belief that outside the Church there is no salvation.

The substratum of this position had and still has a programmatic basis: the Social Doctrine of the Church, which equates sexuality with procreation and consequently disqualifies alterity in these domains. Added to this is the fact of not assuming sex as a source of pleasure in itself, a backwardness of the Gnostics inscribed in stone in the Vatican imaginary.

Heterosexual marriage is the ultimate norm of its model, as confirmed by a high prelate in an interview in which he considered a paragon the rector of a Spanish university whose wife had brought into the world a rather biblical number of children.

This step was but one more in a visible conservative spiral since Ratzinger was elected to office, even though he did not have the charisma of his predecessor. That is what it is about when the Church alludes to its mission to “preserve man as a creature” and disqualifies the notions of “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” against what the United Nations says.

But the dream of reason has its snares. In monasteries and seminaries, as in prisons and the army, it takes all sorts to make a world because diversity is the norm and at the end of the day the curate lives here, in the Kingdom of this World. It was not for nothing that a 14th-century archpriest, a friend of traveling, good food and wine, had concluded that “sinning was a human thing.”

The movement of married priests is growing in strength today, while celibacy remains like an anvil on the head of Peter’s successor. Perhaps if the Catholic Church exercised its pastoral function in a less exclusive and definitive way, it could reduce sexual abuse among its hosts and it would not see the need to hide or cover up priests to avoid scandal, something that Ratzinger did so repeated.

Antonio Machado, coming from deep Spain marked by Ignacio de Loyola and by those women dressed in black who also appear in Lorca, once wrote: “Your truth? No, the Truth, / and come with me to look for it.”