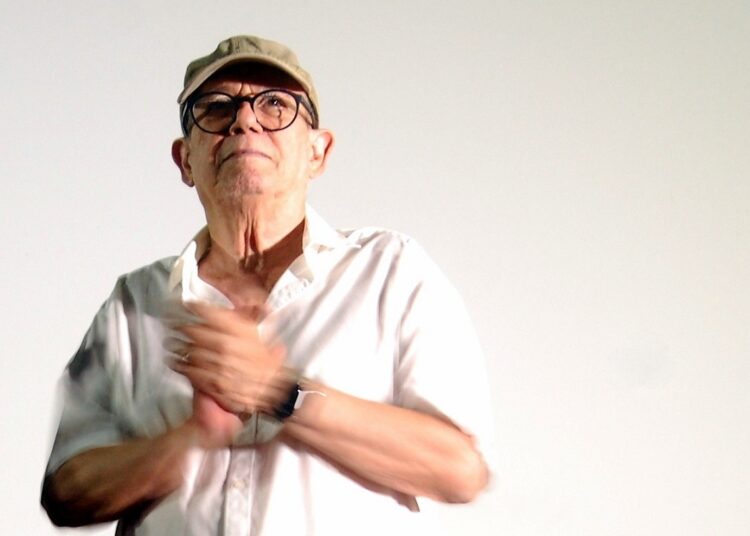

Canarian blood runs through his veins, among many others, as well as African blood, but to a much lesser extent than the former. “I would have liked to have more,” laments Silvio Rodríguez Domínguez (San Antonio de los Baños, 1946), surrendering to the wonders of science while geneticist Beatriz Marcheco shows him the traces and ghosts of his past, in which he shares with Neanderthal man a taste for bitter chocolate.

This architect of language and master of powerful and unusual imagery in his hundreds of songs, however, can only manage to say in the face of such wonder: “Fascinating, fascinating.”

And no wonder. Enraptured, the author of “Ojalá” had before him the annals of his personal history, a rearview mirror that made his gaze wander along a genetic record rooted in 18 generations and some 500 years, which would have made Borges, for example, so devoted to metafiction, burst with happiness, knowing he had been delved into the very core of lineage and time.

Filming was complicated: Gil and Ruta ADN Cuba

The singer-songwriter’s genealogy is captured in one of the six chapters of Ruta ADN Cuba, the first season of a series directed by filmmaker Alejandro Gil, inherited from his colleague and friend Ernesto Daranas. Gil documents the creation of the genetic map of Cuban personalities and interweaves it with their life experiences in an exercise in memory, identity and emotional introspection.

Gil, who achieved fame in 2018 with the film Inocencia, brought Osvaldo Doimeadiós (actor), Silvio Rodríguez (singer-songwriter), Mireya Luis (former volleyball player), Zuleica Romay (researcher), Roberto Diago (visual artist) and Nelson Aboy (anthropologist) in front of the lens.

“It was hard work, incredibly hard. You can’t imagine how difficult it was,” Gil confessed while addressing the Chaplin Theater auditorium, where the screening of the hour-long audiovisual took place last Thursday, August 28. The documentary is a co-production between the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC), the National Center for Medical Genetics and the Ministry of Culture.

Also the director of films such as La pared (2006), La emboscada (2015), and AM-PM (2023), Gil is currently immersed in the making of his feature film Teófilo, a fictionalized account of the legendary boxer Teófilo Stevenson (1952-2012), the Moscow scenes of which were recently filmed.

“We tried to never cut away from the doctor, so that her scientific explanations could be understood, and that’s why we used long shots,” explained the filmmaker, who, to avoid interrupting the specialist’s speech, devised a signaling system with his team so that the camera movement, lighting control and sound architecture of the scenes would unfold in a bubble of technical silence.

“These are life stories that create an extraordinary empathy with the audience, and cinema gives them tremendous luminosity,” he concluded, thanking the series’ protagonists for their collaboration, whom he described as “wonderful beings.”

The clinical eye: Dr. Marcheco

“Let’s talk with Silvio, the kid from the Ariguanabo River, where generations ago his ancestors arrived and took root,” invites Dr. Beatriz Marcheco Teruel, the documentary’s host, standing in front of an almost idyllic landscape if it weren’t for the waterway’s pollution, which Silvio evokes in some of his songs.

At 53, the researcher is a high-profile professional in constant academic growth. She directs the National Center for Medical Genetics in Havana, a PAHO/WHO Collaborating Center for the Development of Genetic Approaches in Health Promotion; she is also a practicing physician and specialist in clinical genetics.

The discipline deals with the study of hereditary diseases within a family and those that, while not hereditary, are caused by alterations in the sequence of DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid, a macromolecule that contains the genetic information essential for the development, functioning and reproduction of all living beings and some viruses.

Marcheco has also conducted important genetic research on the island, such as that which traced the hereditary causes of disabilities and the creation of the National Twin Registry, completed in 2006.

An unexpected and painful event sparked her passion for human genetics. Near the end of her medical studies, she learned that her mother suffered from Usher Syndrome, a rare genetic disease that causes progressive vision and hearing loss. “This became a challenge for me…to prevent, cure or at least help these people navigate life with the least possible trauma,” she told the press at the time.

Between 2018 and 2021, the scientist joined the Cuba Indígena team, a project initiated and directed by Spanish photographer Héctor Garrido, with the support of Dr. Alejandro Hartmann, historian of the city of Baracoa; Julio Larramendi, photographer and visual artist; and sociologist Enrique Gómez.

Marcheco Teruel was in charge of conducting genetic testing on 27 families with Amerindian ancestry in the eastern region of Cuba.

Distant memories: “I am from where there is a river” and Grandpa Félix

Moderated by Dr. Marcheco, the audiovisual captures the exchange of memories between Silvio and Giraldo Alayón, a native of San Antonio de los Baños and the artist’s oldest friend.

“Nothing, we’ve known each other for 74 years. Help!” laughed Alayón, a biologist by profession and a defender, along with the composer, of the Ariguanabo River ecosystem since the 1980s. Finally, in September 2018, after a decade of efforts and paperwork, the Ariguanabo Foundation was legally established for the conservation of the waterway and its surroundings.

There is no doubt that during both of their childhoods the river was — and still remains — the region’s main attraction. Both recalled their first clandestine swimming trips — thanks to one of his uncles, Silvio already knew how and taught his friend — they also fished and played ball in a small field at the back of the singer-songwriter’s birthplace, at 2.5 Caridad Street, where Alayón “hopes that one day” a plaque will be placed commemorating the birth of the famous Cuban musician.

The conversation was not lacking in juicy episodes. One of them, Silvio’s terrified flight from the appearance of a hairy spider — “it was the size of a chicken” — as it crawled through a narrow passage in one of the local caves; or the imposing presence of the artist’s maternal grandfather, Félix María Domínguez, whom Alayón remembers as “a patriarch,” with a graying mustache and a resemblance to General Calixto García, dressed in white, silently dominating the home scene from his quiet rocking chair.

“My grandfather was a cigar roller…he chewed tobacco. And he made his own chews,” Silvio recalls in the documentary.

The musician’s family was one of many that worked in the tobacco industry. His maternal grandmother, María León, his mother, Argelia, and his aunts worked as stemmers (they removed the central vein from the tobacco leaves), and the men worked as cigar rollers.

Silvio recounts the encounter Félix had as a child in a Tampa grocery store with José Martí, on one of the trips the revolutionary leader made from New York in the early 1890s to meet with the cigar makers, one of the pillars of the independence and republican project.

In the song “Yo soy de donde hay un río” (Décimas a mi abuelo), the poet wants to “lie down” in “his own grave, without prayer and without a slab,” with the certainty of the cigar-making patriarch’s belongings, “his chair, his knife, his chew, and his Nevada crown, which I also know is his knee.”

The Olivette

The investigations carried out by Dr. Marcheco’s team uncovered another interesting fact about Félix María’s life: that in 1908, at the age of 21, he was a passenger, along with his father, Francisco Domínguez, on the steamship Olivette, bound for the United States.

Launched on July 15, 1887, the ship was used by José Martí on his frequent trips to Key West. On the first of these voyages, the ship was decorated with Cuban flags and an onboard band played the Bayamo anthem.

But there’s more. The Olivette was the ship that carried, as part of the correspondence between the United States and Cuba, the order for the uprising of February 24, 1895, sent by Martí to Juan Gualberto Gómez, one of his trusted men and Delegate of the Cuban Revolutionary Party on the island.

In 1918, the ship ran aground 8 miles east of Havana harbor due to heavy seas and fog. All attempts to refloat it were unsuccessful, and it finally sank a hundred meters north of Punta El Judío, on the western shore of Bacuranao beach, opposite the current Granma Naval Academy in East Havana, where it still lies.

Dr. Marcheco invited Silvio and his family to visit the wreck, which rests on the seabed at a depth of about 15 meters. “Well, we survived,” the singer-songwriter laughed, back on land and still wrapped in a wetsuit.

A fountain pen with red antiseptic solution

Gil’s audiovisual material captured other moving scenes. During a visit to Ojalá Studios, the geneticist became interested in a binder and a fountain pen resting on a piano.

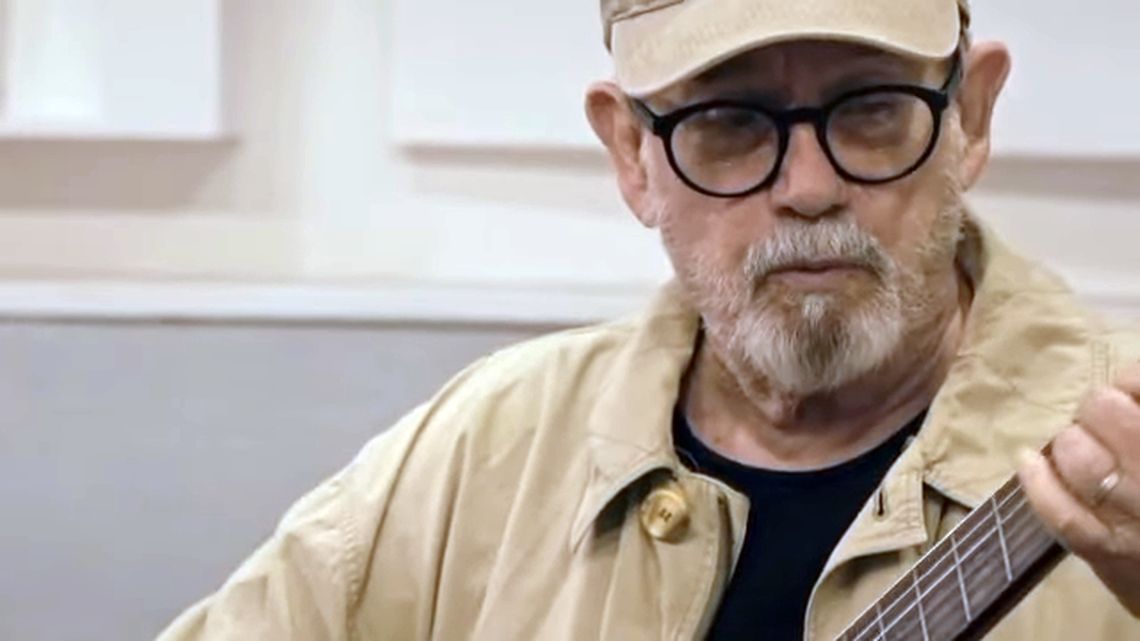

“Vicente Feliú [1947-2021] gave me that pen when I was leaving on the Playa Girón, and I used that pen to write everything I wrote,” Silvio recalled, alluding to his adventure on the fishing boat where he enlisted in 1969.

The experience lasted until January 1970, during which he composed 62 songs in one go, some of which later became classics such as “Ojalá,” “Resumen de noticias,” “Cuando digo futuro” and “Playa Girón.”

He met Vicente, who would soon become another founder of the New Song Movement, when they were both in high school. “I was in night school and he was in day school, in Havana.” Their lives diverged for three years. Silvio joined the army as a recruit, and Vicente went to the countryside to harvest coffee. When they reunited, both composed songs accompanied by the guitar.

“By the way, it wasn’t ink in the pen, because there was no ink; it was a red antiseptic solution ,” recalls the singer-songwriter, whose fountain pen traveled with both of them to Angola in 1976, just a few months after Cuba stationed an expeditionary force there to stop the South African invasion at the gates of Luanda, an episode described by the superb García Márquez in the report “Operación Carlota,” published in 1977 in Tricontinental magazine.

“We both worked with that pen,” recalled Silvio, who is also a draftsman and mentioned to the doctor about the giraffe she had observed, which he painted for his daughter Violeta, then a child, while he was in Angola.

Music, poetry and decency

Silvio says that decency was an important value in many families at the time. “There was talk of being decent, of having proper social behavior and of being considerate of others.”

From Dagoberto, his father, he inherited “a love of reading,” despite the fact that he had a rudimentary education, “since he had worked in the fields since he was a child,” although “he always had a great interest in books and literature. He was very fond of theater and poetry, and through him I learned the poetry of Martí and Guillén; a man with barely completed second grade, who enjoyed reading profound poetry.”

On his mother’s side, the main legacy was music. “Everyone in my mother’s family was a musician, starting with my grandmother María, who sang old songs at home like ‘El colibrí,’ a tune I sang a lot and that I learned from her and later from my mother.”

Argelia Domínguez formed a duo with her sister Orquídea when they were teenagers and participated in cultural activities in the town. However, the social prejudices of the time made it difficult for them to continue their artistic careers, something that did not happen with the men in the family, who founded musical groups like Jazz Mambo Beat.

Bitter chocolate, Eusebio Leaand a cosmopolitan Martí follower

The genealogical report obtained from a saliva sample establishes that Silvio Rodríguez possesses 291 sections of DNA inherited from Neanderthals, some related to physical and physiological characteristics such as blushing easily or the ability to sweat during exercise.

This inheritance dates back to our distant ancestors and demonstrates how fragments of that ancient genetic line are still present and affect current traits. Among these peculiarities, in his case, his fondness for bitter chocolate stands out, a trait that links him — metaphorically — to those humans who lived some 400,000 years ago until their extinction around 40,000 years ago.

Furthermore, Silvio has a genetic predisposition for having an ear for music, an ability that allows him to hear and reproduce melodies with great fidelity. This ability stems from a deep connection with his family heritage, especially with his mother and grandmother, who had a notable musicality that influenced his artistic development from childhood.

A curious and significant fact is that the musician shares a common ancestor with the historian Eusebio Leal (1942-2020), with whom he would be a fifth cousin, sharing a grandfather approximately 180 years back, in the sixth generation.

“I’m not surprised. And I’m sure it wouldn’t have surprised him either. We were very close,” commented the singer-songwriter, remembering the Havana historian, whose painstaking work restoring the colonial and republican heritage returned much of its lost majesty to the capital.

Regarding his genetic origins, 87% of Silvio’s genetic information comes from Europe, especially Spain and Portugal, with a strong presence of lineages from the Canary Islands and the Azores. He also has 4% African DNA, mainly from West Africa, and a small proportion from the north of that continent and other regions of the world, reflecting his multicultural and multiethnic heritage.

Silvio’s maternal lineage is marked by the H4A1 branch, which emerged approximately 8,500 years ago in Europe, linking his genetic history to regions of the Caucasus and the so-called Old World.

Through the Y chromosome, his paternal lineage belongs to the RL51 branch, common in European men and related to historical figures such as King Niall of Ireland, who ruled in the 5th century, reflecting a connection with ancient cultures that extends back to the Vikings. “The adventurer definitely came to me through there,” he stated in the documentary with a touch of humor.

After hearing the genetic report from Dr. Marcheco, he confessed that it caused him “a little fear,” “because I think of myself differently,” although he considered the information “fascinating.”

“I see that in every sense we are also the result of many things. We are so closely related that we don’t even know it. And we should get along better, right?” the singer-songwriter added, confirming his universal identity and championing understanding and dialogue as a civilizing necessity.

“One is truly cosmopolitan, as Martí said,” he recalled, quoting one of his paradigms.

First consequences: chromosomes leap into the score

The discovery of his genealogical album has not only been an opportunity for wonder and reinterpretation, but also a channel for composition.

Silvio’s musical career includes film scores as early as 1968 with “Al sur de Maniadero” (documentary); “Columna Juvenil del Centenario” (1970) and “República en armas” (1974). His mark is also evident, among other productions, in “Como la vida misma” (1985) and in a pair of songs that became classics, both in his music and in national cinema: “El hombre de Maisinicú” (1973) and “Balada de Elpidio Valdés” (1979).

We don’t know if the creator, born at 4:30 a.m. on Friday, November 29, 1946, had already planned to compose the soundtrack for this sixth episode of the series Ruta ADN Cuba, either before or after the laboratory results.

In any case, the music, in this case, is a discreet traveling companion to the documentary’s narrative, but — and this is unfortunately unknown to the viewer — it is the result of a “scientific subjectivity,” if the term can defend itself from the oxymoron. This is what the author himself tells journalist and editor Mónica Rivero exclusively via WhatsApp.

“A melody can be extracted from each DNA strand, based on notes and intervals, so I made the music for the episode with the intervals of my own genetic code. I’d say it has to do with me. Especially when I organized it and added harmony, because before that, it’s something purely melodic. I called it — what other name? — ‘DNA.’”

Postscript

A few moments before the screening, an effusive official from the ICAIC called the artist to the microphone. “What does Silvio Rodríguez expect from this work of art?” she blurted out.

“I hope it serves a purpose. Quite simply. Thank you,” Silvio responded, playfully harsh, trying to escape the vainglory of his genius and the overwhelming weight of his name.