Ernesto Daranas has lived all his life in Old Havana, a landscape he has taken to the big screen, not as he would have liked in all cases, but glad to be able to work freely. This is a fundamental premise for the director of films such as Los dioses rotos, Conducta and Sergio y Serguei, recently awarded a special prize in Moscow.

In his youth―he was born on December 7, 1961―it was almost impossible to study cinema in Cuba, so when he finished senior high he decided to study for a Bachelor’s Degree in Geography in the Pedagogical School because “there were not many options of art schools in the country. I really chose this career because there were few boys in a classroom of 30-odd girls (he smiles), and it seemed very appropriate at the time.”

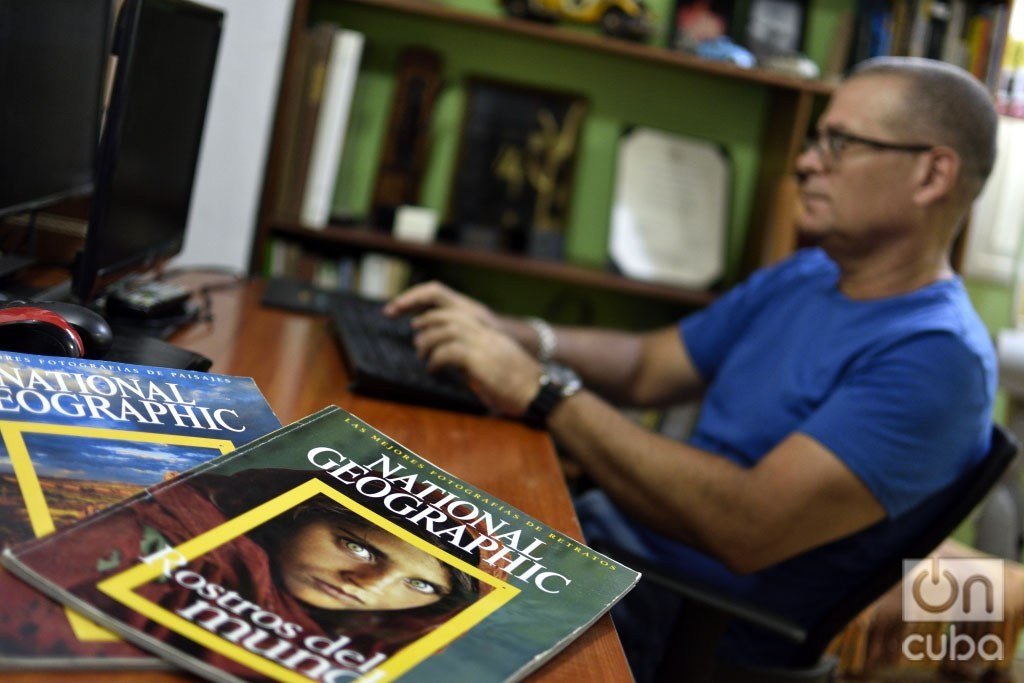

In his apartment in Havana’s Historic Center, Daranas agreed to talk with OnCuba about his work, what motivates him to write and, of course, Cuban cinema.

How does a Bachelor of Geography become a film director?

“When I was in senior high I had a club of cinema buffs with a group of friends and we filmed with 8 mm films. We had to even film for four continuous hours because there were no editing options, everything was filmed in one try, with a lot of rehearsal and without sound, which was done independent from the celluloid, which was common at the time.

“It was a very good opportunity to study that career because I had the luxury of having great teachers at that time; beyond science, subjects such as history and philosophy were luxurious because they were taught by excellent teachers. In the pedagogical school I did not stop being linked to cinema, I continued with the rolls of film doing what I could at that time. There must still be some saved there,” he points to a corner of his workspace.

***

Daranas’ first training as a writer was on the radio, where he maintains a daily program on Radio Taíno and a weekly program on Habana Radio. “These are programs that I have tried to stop doing at some point due to time and work problems, but it has been impossible for me because of my commitment to these spaces and because I like the radio, it is a medium that I appreciate very much,” he confesses.

“I started when I was still a student, I was around 19 years old. Also because of something that was a bit romantic because my father was a famous radio writer, he wrote series, radio soap operas and I used to see that this was his life. He would spend all his time here in this same room, doing what he liked.”

Returning to cinema, how much of his life does Ernesto Daranas reflect in his films?

Absolutely everything. In the case of Los dioses rotos, the context is my environment, a story that haunted me for years because it was based on a documentary I could never make that was called Las 13 sillas, where I interviewed pimps and other people who were engaged in that business, when it was practically in its beginnings. I collected a part that was filmed and one that was recorded, almost 100 interviews.

When I realized that with the material I had it would not be possible to make the documentary I wanted because it was an issue that nobody wanted to address, I thought about another form for the project. Through a call from the Ministry of Culture, I was able to present a script I had written, the product of many years of work and that is how Los dioses… began, in fact, there are testimonies in the film that are word-for-word what the interviewees said.

The nicest memory I have of that film was at the Havana Film Festival when we met part of those involved in the initial project, even some for whom I was able to get tickets to see the premiere. In many cases they had been reinserted into society and it was a very beautiful experience.

In the case of Conducta it focuses on my childhood. A story enriched with the contribution of the same children in the film, who incorporated their experiences such as dog fights, because in my time that didn’t exist, but it was part of their reality.

I was half-dyslexic and that created problems for me in school regarding learning, in addition to the fact that this neighborhood was not as nice as it is now, this was tough. Those influences were there on the street, no matter how much my parents tried to distance me from that world.

Sergio y Serguei was the first film I would have wanted to do for cinema. I knew the story about Krikaliov, a Soviet cosmonaut trapped in the Mir space station and a few years before I had met a group of radio hams from San Antonio de los Baños who had contacted Serguei. From then on, I had the idea of merging both stories into a fiction story, two characters who are like shipwrecked people in history and come together in two parallel realities that suddenly bifurcate.

This was also a topic that touched me in some way because of the career I had studied and everything that Sergio’s character experienced, even the Azuquín, the common story of many of us in that circumstance of the Special Period.

Prostitution is also a referent in your filmography.

Sometimes the origins of things are forgotten. Actually this phenomenon started being seen in university circles, not later, during the crisis of the 1990s. In the 1980s there was a famous article in the magazine Somos Jóvenes, “El caso Sandra,” a subject that the journalist addresses very much in tune with the reality of the moment. I graduated in 1983 and as a student I began to see this phenomenon among my women friends, because they spoke languages, they had a certain intellectual level and they could get into hotels.

It was something that caught my attention, I saw it as recycling: the tenement house in front of my home had been a place that catered to sailors before the triumph of the Revolution and I knew people who had dedicated themselves to that, even some of my classmates were daughters of these people, a normal environment because this was a port neighborhood.

We can’t think that this phenomenon was suddenly born and throbbed in the 1990s with the crisis, it was a process. I started making these interviews in the late 1980s and ended around 1994-95. It was a subject in which I got fully involved, especially highlighting the dialogue between that phenomenon, which exists in all parts of the world, with the country’s politics, an analysis of how an attitude in politics finds a reflection in people’s lives, regardless of the crisis; they are ways of acting and behaving that people are seeing and that influence society’s values.

What motivates you to write a story?

I’m not obsessed with filming. It doesn’t worry me so much. I have the need to write things based on feelings, they are not always ideas. I think that more than ideas, what has always moved me to film in fiction have been sensations concerning nationality, the city in particular…, I am very Havanan and the way I see the city change has almost always involved pain, because of the losses. That has almost always been a trigger that has led me to find a way to share that.

The same in fiction, on television or in documentary, Daranas has enjoyed some independence when it comes to work, whether in productions by order or independent.

Independent production has many aspects. When I was working outside of Cuba, there were style cards for everything, to give you an example: the camera cuts, the shots had to be specific, this subject can be dealt with and this one can’t…those things were present in that work I did.

I have also filmed many things on my own. I just went to film the pilgrimage to the Church of Las Mercedes (Our Lady of Mercy), which I do every year. I enjoy these things a lot because it allows me real explorations in time and helps me to maintain that spirit of independence, because when filming in any production you are subject to a schedule, an element in the audiovisual that takes a lot of time.

One aspect cannot be missing in his work: “The first thing I have in mind as a director is creative independence according to the nature of the project. There is always a dialogue that you have to establish with the producers, whether independent or from an institution. There are always common interests and aspects in which we don’t coincide, so that creative independence is fundamental.

“Censorship is an objective and real phenomenon, it exists. Possibly the most independently creative works of Cuban cinema were made within the ICAIC in the 1960s, and they possibly continue to be those with the greatest artistic and complex imagination of Cuban cinema. The essential thing about independence is the creative aspect, and I don’t care who I work with as long as that is a possibility.

“I have been fortunate that in the three films I have made, although I’ve had to discuss a lot, I have never been censored, but it’s something that has happened to many people,” recognizes the filmmaker, who also likes to work with young filmmakers. “I always change many things in the filming process because their views help me a lot. It is a much more contemporary perspective.”

Regarding the work of young Cuban filmmakers today…

It’s no less true that there is a cinema made by young people who have worked a lot, which has a very high value because it’s the cinema that has opened our image to other perspectives and it would have been very difficult to have filmed in an institution with those views. That cinema in this moment embodies a fundamental part of the best of current Cuban cinema.

It is a subject that involves many aspects and an important complexity in this new scenario that supposedly can be possible now, which is yet to be demonstrated even in this first stage. The main thing is that this creative freedom can be preserved.

The attack on that independence that has been obtuse on many occasions, as happened in the Sample (of Young Filmmakers) a couple of years ago, has established divisions that are sad, sometimes the necessary dialogue is not propitiated. I think it is a prejudice that must be overcome because there will always be and has been independent cinema.

The issue of seeing so much talent emigrating makes me very sad, I have lived it because I work a lot with young people who have graduated from film schools. That is one of the biggest problems Cuban cinema has for there to be continuity. Let’s see if in this new stage we are living it’s somehow possible.

What cinema does Cuba need?

A diverse cinema. There is a cinema that has to make things complex and polemicize, which in artistic terms and in content has to present the artists that we have that many times don’t have access or the possibility of filming. That is the cinema that is art.

But you also need a cinema that connects more directly with the public, that takes people to the theaters. We know that the cinema with the greatest artistic imagination is not always the one that draws the most public.

There has to be a diversity that is only possible if production increases, another of the disadvantages of Cuban cinema, the little that is produced, which would also change if access to what was filmed was more democratic, then those more complex views would find their space for expression. A cinema where there is cinema, that makes people want to go to the movies.