Text by: Rubén Padrón Garriga, Maysel Bello Cruz and Darío Alejandro Escobar.

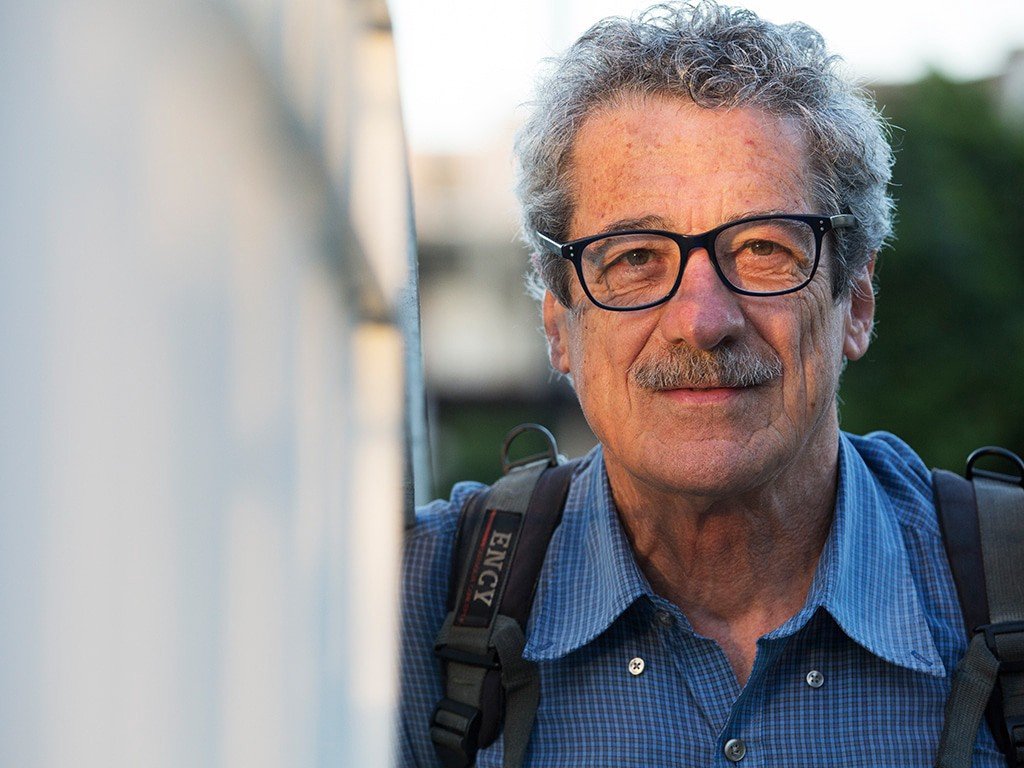

You have to love Cuba to make good cinema about it; that also means betting that all those who love it fit in it. From his Young Film Festival (ICAIC) guide, the defense of prohibited works, the opportune demand for a regulatory framework for independent cinema, the disinterested and affable teaching of a novice who faces a camera for the first time or rebellion of a street protest, Fernando Pérez has done a lot for his country and its cinema. His indisputable work has established him as the most important living filmmaker we have on the island, but his actions and vision make him one of the most valuable figures in Cuban culture.

In this interview, Luz Nocturna explores his facet as an artist and thinker, his particular vision of cinema and the social processes we are experiencing today. Fernando supports his ideas with the courage and independence that comes from being a transparent and authentic man who wants a Cuba like the one Martí dreamed of, and everything that stands in the way hinders him.

You made your debut as a director of feature films with Clandestinos and, for more than 30 years, you have moved through various genres and styles. How do you feel that has changed your way of making films throughout your career?

In many ways. I like to make films of all styles. I am not affiliated with a single way of narrating. In fact, analyzing my filmography, I feel that there are two lines: one that is more classic in the narrative sense, with Clandestinos, Hello Hemingway, José Martí: el ojo del canario; and another with a cinema that is more about the metaphorical, with a much more subjective language, with Madagascar, La vida es silbar, Madrigal and the most recent one that I am doing.

I am a filmmaker, but I am also a movie buff. Watching movies was my way of learning cinema, although of course I learned a lot as an assistant director. I always try to renew myself. I try to go down a different path that is not determined by what I already know. I think I’ve kept that spirit.

In your cinematographic work, two great films of the Cuban historical drama stand out: Clandestinos and José Martí: el ojo del canario. On some occasions, they have even been used as audiovisual material for history classes. However, they are far from any instructive story about the context and sacralization of the figures. Do you think there should be a necessary relationship between film production of a historical nature and didactic intentionality for the public? When you approach these themes and figures from our history, what are you looking for as a creator?

I think there are many ways to approach history. The first is that of the historian and must be marked, as far as possible, by objectivity. The historian tries to approach the historical event as precisely as possible. On the other hand, the approach of art to history is not necessarily based on that premise. It must be based on the historical event, but from another perspective.

If the historian is in charge of the general, the artist goes to the particular. I’m going to put an example. We all know what happened in the Burning of Bayamo, the historical event and what it meant in the struggle for independence. However, I remember reading a novel called La concordia, in which a chapter narrates that Burning of Bayamo, but based on the individuals who did not want to leave their homes for whatever reason. Within the same historical event, there were individuals and situations that were not the same. That impacted me a lot, because I think that is what defines the performance of art when dealing with history.

I tried to do that, not so much in Clandestinos as in José Martí: El ojo del canario. In the latter, I was faced with a figure that has a very powerful meaning for every Cuban, but on the other hand it has also become a stone statue; a certain sanctity surrounds him. I had to get him down from that statue. I believe that Martí has come down to us in such a powerful way not only because he was an excellent poet, but also because he viewed and practiced politics with poetic sensitivity. That was what I tried to express in the film.

With Clandestinos it happened to me that, since I was a teenager, I wanted my first film to be about that subject. And I also had to walk a path that I didn’t know in fiction and an action movie allowed me to do it. So, I tried to humanize those characters: an Ernesto who was afraid of torture, a Nereida who followed Ernesto more out of love than out of political awareness and, most importantly, that they were young people who danced and enjoyed themselves like any neighborhood kid. Always respecting the epic and the historical event narrated from the action cinema.

Havana is a constant character in almost all your work. In some, you show it splendorous; in others, rebellious, but also in ruins. How much remains to be told about that Havana and how to do it, moving away from the simplistic and binary story of the socialist paradise or the totalitarian hell?

I feel Cuban, but very Havanan. And it happens to me that my emotions vibrate with those of the city. In my film experiences outside of Cuba, I don’t feel the same way. This is where I feel in my element, where I am more creative. I recognize myself in every event that happens. And what most characterizes our city is that anything can happen.

I really think so: Havana as a cinematographic space is endless and that has to do with the people who inhabit the city. Havana without its people would be just scenery. This city is full of stories, not just right now, but back in time. I think the young filmmakers are going to tell them. My films are there and now I’m trying to make another one called Nocturno. It is in the script phase. I will try to express cinematographically what I have lived and others have lived from 1961 to the present. Of course, with its time jumps. I hope I have time.

Cinema, from the very beginning of the Revolution, has been one of the areas of art in which there is the most public debate. Filmmakers have always been artists committed to the destiny of their country. How do you see that process today? How many of these debates have moved to social networks and what ways do you find to intervene when you think it is necessary?

I have a melancholic character and that is why nostalgia sometimes dominates me, although I don’t like it. I like to do it from the dynamics of the present. However, I remember the 1960s with nostalgia. Not only in Cuba, but also in the world. Everything seemed possible. My generation was changing this country. But really, from the essences. Everything that needed to be changed was being changed. The dynamics of thought vibrated and, although everyone did not think the same, the predominant ideas were those of change. It is true that there were many ways to propose that change, but it was discussed publicly.

After that time, that freedom has been limited. Above all, in the mass media. There, the debates and panels almost always show more a predetermined conclusion of a topic than the process itself. I think it is a great loss.

Now, with the networks, many young people have found the space that they do not find in the more traditional media. I see the networks as something positive, but also very dangerous, because they have become a place highly contaminated by extremism. It is navigated very superficially and there is no exchange with depth and respect. Of course, light discussions are also needed. Not everything has to be complex.

Apart from the ones I have to communicate with, they don’t attract my attention, although I’ve had to resort to them to express ideas that aren’t published in other spaces. In any case, I have always tried to express the ideas that move me as an artist and as a citizen through my films. I think that is the best way to participate. Except emergencies.

You have stated in other interviews that you started at ICAIC as a messenger, without any contact in the film world, or much training in terms of technique and method. The institution itself helped in your formation and opened up opportunities for you to grow. Today we have academies such as FAMCA or EICTV, but what role are these institutions playing today — especially ICAIC — in accompanying the intellectual development of Cuban film professionals? Do you think that today a young man, the son of a postman, has the same opportunities that you had to become a director?

They do not have the same opportunities because the context is not the same. In 1958 I dreamed of making movies, but the truth is that I never thought I would make it. When ICAIC was created in 1959, it was a dream for me. I entered ICAIC filling out a form and they called me to be a Production Assistant C. On paper it was that, but in real life I was a messenger. I lived from here to there carrying filming permits and running errands. However, there was a new generation being formed as filmmakers. There were two ways:, the ICAIC sent some young people to study abroad; and we others stayed here learning in practice.

ICAIC was a production center and, at the same time, a school. And when I say “school,” it wasn’t an academy, thank God. What was done was to work and argue constantly. That was breathed in the atmosphere of those years. They had film debates, a library where the latest came, not only about cinema, but also world literature. I remember that I was an assistant in the library, I also helped with the Russian translations and the first edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude fell into my hands when García Márquez was not yet known, as happened later. I also remember a pamphlet that was published on the latest aesthetic discussions, structuralism when it began, the New Wave, anyway….

And not only the ICAIC. It was the time. I was a mid-level technician and, when I entered university, I had Mirta Aguirre, Camila Henríquez Ureña, Roberto Fernández Retamar, Beatriz Maggi as professors. Each one was a Master. We, those of us who were starting at that time, grew up on that fertile ground. That always accompanies me.

To recover that, we can do what I have always defended from EICTV. In other words, that schools are not academic, but spaces for creative searches. I still think that cinema is learned, but not taught. Almodóvar also says so. Now young people also have technology in their favor. I made my first fiction film when I was forty years old. In any case, cinema is not easy to do. Not yesterday, not now. In all times it will be necessary to fight and persevere to achieve it.

Last year two very notable photographers who were frequent in your work died: Raúl Pérez Ureta and Jaime Prendes. How was it working with them?

It is the first time that I am going to talk about the loss of Raúl and Jaime. Raúl was my brother. We grew up together from the ICAIC Newsreel. He had a very particular nobility. My next film will be dedicated to him. Almost all my cinema is with him. The pandemic greatly affected him, but such is life. My generation is already ending.

I met Jaime Prendes on the Isla de la Juventud. He was a very special human being. He was very free, very creative, very unassuming. Without any vanity. His death also had a great impact on me because it happened suddenly. Assimilating those two deaths has not been easy.

You recently finished shooting your most recent film, Riquimbili. What can you tell us about it?

After having made Insumisa, which is a much more classic narrative film, I wanted to return to a cinema where I would play more with the narrative structures and Riquimbili is about that. It’s several stories intertwined by a plot line that can change a lot. Although the genre that mainly defines it is black humor, there is also a tribute to other genres such as melodrama, musical, etc.

It has me in tenterhooks because, until I finish it, I don’t know if it’s going to work. The process has been complicated because the pandemic has delayed it longer than usual. That had never happened to me. There was a time when I thought it would not come out, but luckily, we did it.

And about Cuentos de un día más?

It was a very nice experience of solidarity coordinated by ICAIC. At a time when the pandemic was becoming more aggressive and almost all of us were in compulsory confinement, the ICAIC presidency had the idea of convening this project. Young people and also specialists of my generation participated.

I really enjoyed it because of the way it was done. Note that I think something protected us, because sometimes without permission we went out to shoot and, without evaluating the final artistic result, it seemed impossible, but it was done.

This process demonstrated the quality of human beings and the quality of professionals that we have. We can still do great things. All you have to do is motivate them, give them the opportunity and the space. Cinema is not a problem. Cinema is a contribution to the spirit of the nation.

In 2013, you were part, along with other filmmakers, of the group known as G-20, an articulation for the most visible proposal that sought to recognize independent audiovisual production. In 2019, Decree Law 373 was issued, which provides the legal framework for independent production companies. Some creators in the field have branded it a “gag law”; others recognize its value for the development of audiovisual production in a self-managed way. As one of the leaders of that proposal, how would you define independent cinema for the current Cuban context? How much has been achieved in its recognition and how much remains to be done?

The G-20 was the head of a much broader movement. For me, what marked that moment was the Assembly of Filmmakers. I miss that meeting a lot because today it no longer exists. Call me utopian, but I dreamed that it would continue. Many of the demands were channeled through the G-20. The most important were achieved over time. It took a long time, but it happened.

The Development Fund is very important, to give an example. The way in which the principles of the Development Fund were conceived is quite open. In any case, while we are fighting for a Film Law to come out that regulates the activity, there is a pending account, which is the exhibition. Because censorship is still taking place over time.

It is a lesson not learned. ICAIC, as the governing body, has every right to decide what it exhibits or does not exhibit, but it cannot be the only option for the diversity with which the Cuban audiovisual is expressed and will continue to be expressed. Those spaces have to exist and open up without stigmatizing them. Until works are stopped being prohibited almost always for ideological reasons, there will be contradictions. That is a pending discussion. And this is not only about cinema; it also applies to all the arts in Cuba.

Independent cinema right now is the fundamental part of Cuban film production. Even ICAIC itself is collaborating with independent production companies. Independent cinema is here to stay because it is the evolution of a production process that has lowered its costs through the development of technology, but also the evolution of our society.

Some time ago it was asked through a questionnaire what we understood by independent cinema and the answers were very varied. In my opinion, this type of production is defined by diversity, because independence is given by oneself, if we are talking about artistic independence. I consider myself an independent filmmaker making films with ICAIC, making films without ICAIC, but always making films that I have wanted to make. That is an attitude. Young people are going to continue creating their production companies beyond the decrees. It is good that the decrees exist, but that process of evolution is what is going to shape the reality of Cuban cinema.

I have very nice memories of the way many young people who I didn’t even know expressed themselves. And it was very sad that the dialogue did not continue. The reality is that it was going to be very difficult to reconcile the opinions of the N/27 group, because there were all kinds of opinions, but I think that there was a lack of effort, a will on the part of the authorities for that dialogue to continue. I think the diversity of the group should have been dealt with, instead of making a selection to see with whom they talked or didn’t talk. That marked the break.

That kind of thing makes a lot of young people become frustrated. I have the impression that, due to the pandemic and the economic reorganization, many young people have broken down and are leaving. More and more young people are leaving because they cannot find the space to express themselves and develop. That is the worst thing that can happen to us as a country. I feel that young people are always faced with what they are allowed to do and not with what they need or want to do based on their own ideas, which are often different from ours.

Those restrictions have to be lifted. As the restrictions of the economy have to be lifted. I am not an economist, but we have taken so long to make some decisions that now is the worst time and they do not give answers. The official discourse goes one way and reality on the other. That is very harmful. People need answers, they need dialogue. How to maintain a dialogue? At the level of the opposition? I don’t want to be an opponent, but how am I going to follow you, if what you tell me has nothing to do with my reality?

I am very concerned that time is running out and the fracture is getting bigger. And, as long as I can, I will continue to fight alongside the young people who want to change the country in a positive way. The change is going to come from the young; it’s not going to come through the “established channels.” They are going to more or less make mistakes, but the change is natural and it is going to come from them.

Imperialism is going to be there, the CIA is going to be there; it’s like the story by Monterroso, but we can’t depend on that. We have to bring about change for our own good. As long as we remain closed, with the same discourse; as long as our media are not opened up and the Mesa Redonda TV program follows a single line, this is not going to improve.

Ideas triumph because they are the ideas that an era needs; they cannot be imposed. Participation mechanisms have to be created where people can really do it. Prohibition and repression are not going to lead us to a better country. If the CIA and all these people manage to make a soft coup, it’s because we haven’t changed what we should have changed long ago. I don’t want that, nor am I interested in Biden’s politicking. To me that country seems to be heading for fascism, but we cannot depend on that. We have to achieve a more plural country, as Martí wanted. That was the idea of the Revolution for which we fought. And I feel a revolutionary.

What future do you predict for Cuban cinema?

Rather than the future, I prefer to think about the present. The present that we manage to develop now will determine the future.

***

* This article was published in Luz Nocturna, OnCuba reproduces it with the express authorization of its publishers.