Por Norge Espinosa

As if preparing myself for an arduous journey, last night I watched the almost three hours of Blonde, Andrew Dominik’s film that takes up the homonymous novel in whose pages Joyce Carol Oates reinvents the main passages in Marilyn Monroe’s life. It was premiered, thanks to the 22 million dollars that Netflix allocated to its budget, just a couple of months after Elvis, the Baz Luhrmann biopic that approaches the biography of the other great icon of American popular culture of the 1950s. Marilyn and Elvis, still adored by crowds, embody in many ways the obsessions of fame and the contradictions that Hollywood cannot hide behind the figure of a superstar. The bright and dark extremes of lives that, by becoming public domain, create myths, while pulverizing them over and over again. In Blonde, Dominik wanted to peek at the less luminous point of Norma Jeane Baker, that young woman immortalized on the subway grill, whose skirt rises to let us see her legs, while she smiles eternally before the cameras and under the most blinding lights.

Right there the film begins, which, to say it once and for all, seems to me excessively long, pretentious, and which is carried away on many occasions by a metaphorical desire that, while slowing down the plot, induces a reading of its protagonist that only insists on its frailties. Located in a dangerous territory (like the novel, it announces itself as a fantasizing handling of details and anecdotes with great freedom, mixing rumors with proven facts), Blonde at the same time handles with a certain opportunism her status as a mirror of someone who, beyond all of that, is Marilyn Monroe, passes from hand to hand through men also known as real beings, cites movies and events that we can find in all her biographies, but gives us a sometimes tendentious reflection of that same human being. If in Oates’s novel the real names of many of these men are eluded, here the biographical, in that sense, leaves no room for doubt. The film is called Blonde, it reveals intimacies of a girl who rises in her quest for stardom, and that woman is definitely Marilyn Monroe. Or Norma Jeane Baker. As a Gemini, after all, Monroe could be two different beings at the same time. And from the struggle between one and the other comes this agony, which the film offers us as someone who discovers a path to holiness, even if it is doubtful.

In a surprising photo, the Marilyn Monroe who came to Madison Square Garden to sing “Happy Birthday” to John F. Kennedy, smiles by the side of Maria Callas, during the reception that night. In “María by Callas,” Tom Volf’s excellent documentary, the diva thoroughly explains that dichotomy, between the woman she wanted to be and what her role as queen of the opera demanded of her. For both the Niagara actress and Onassis’s mistress, that battle proved fatal. And that anguish has marked the way we still celebrate and discuss them today. Marilyn Monroe was, according to Hollywood, the most resounding expression of the bombshell, the blonde that no one could refuse. Behind that mask, there was Norma Jeane, the young woman who spent her childhood in orphanages, the one who had to deal with a mother who ended up losing her mind, and who read Chekhov with the hope of one day surprising Elia Kazan or Strasberg interpreting Natasha in The Three Sisters. The 1962 suicide (still surrounded by many suspicions) ended all this. Naked, in her bed, with her hand on the phone, Norma Jeane was found dead. Marilyn Monroe, the platinum goddess, outlived her. She survives her. She will outlive all of us.

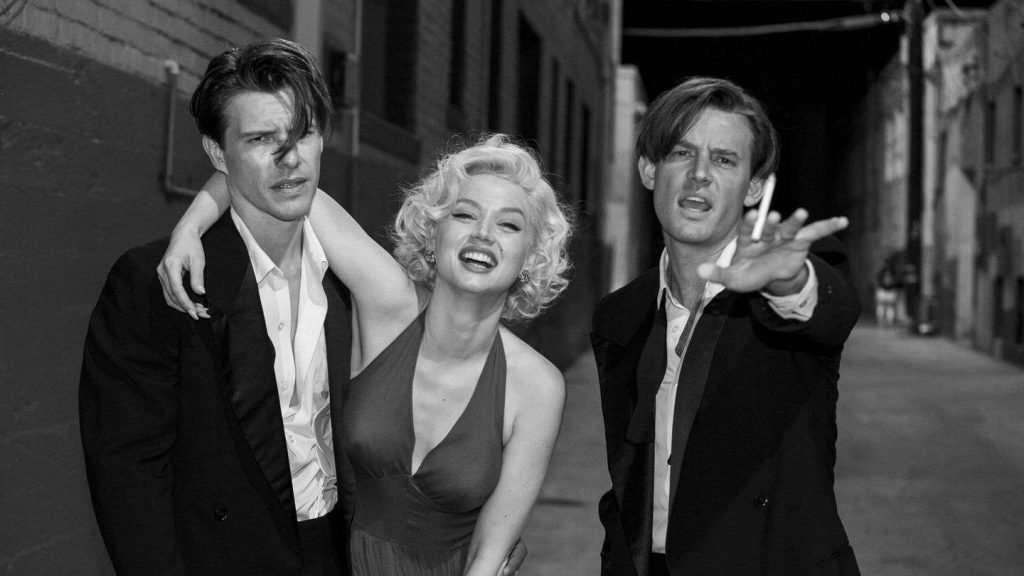

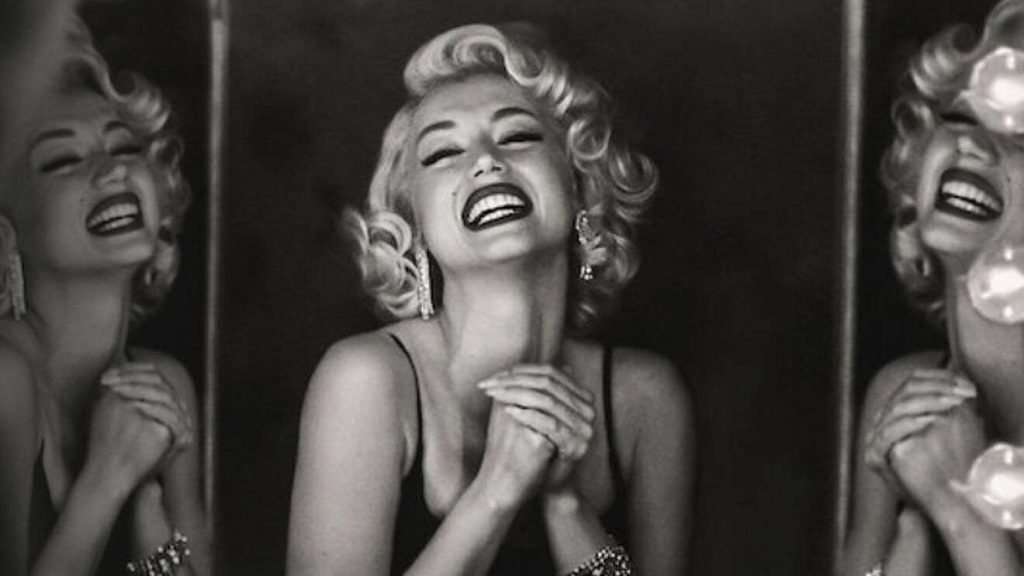

With scenes in black and white and color, depending on the dramatic accent that the director wants to underline, sequences that meticulously reconstruct shots of the Monroe films, and a very remarkable sound work and excellent soundtrack (Nick Cave and Warren Ellis), the film comes close to an almost documentary reconstruction of the star’s life, choosing as film sets the house where Monroe died and the apartment where she lived with her mother. And all this attests to a great commitment to what is shown to us, sustained with a very praiseworthy effort by Ana de Armas in the main role. She is not the first nor will she be the last to take on the monumental challenge of bringing her to life on screen, but the truth is that she has gracefully come out of such a challenge, even above the tearful and reductionist vision that the script imposes on her, in that effort to transform the figure before which she surrenders as a kind of almost absolute victim, in a rare ordeal towards her own suffocating glory.

What bothers me about this unnecessarily long film is that vision of a Monroe who apparently has no more meaning in her life than to seek in any man who crosses her path as a shadow of the father she never knew. “Daddy, daddy, daddy,” she repeats ad nauseam in one scene after another. And she cries, and cries, and cries, as if everything came down to this in her 36 years of life. And Norma Jeane wasn’t just an easily handled doll. Any of her biographies (I still recommend Donald Spoto’s among them) reveal other elements of her character. Let’s not forget that she founded her own production company, that she chose her roles in powerful discussions with the studios, that she challenged George Cukor, in the middle of filming Somehing’s Got to Give, precisely to go to New York to celebrate Kennedy’s birthday, her lover in those days of 1962. Her diaries, her writings, attest to a woman who, in full doubt, also handled certainties and had determinations about her career. In this in extremis Freudian variant of her life, Monroe is an underdog, surrounded by men who mistreat her, manipulate her, and abuse her without showing too much mercy for her person, as if the entire male world had been reduced to thereto. And to make matters worse it is Billy Wilder, perhaps the one who best directed her, who bears the brunt of those sequences that reconstruct the filming of Some Like it Hot, Monroe’s greatest achievement in comedy, along with her appearance in Bus Stop.

Add to this moments where Dominik pretends to be Terrence Malik or pretends to make more experimental films (abstract images, the fetus that talks to Marilyn, which seems to come out of the end of 2001, a Space Odyssey, and the nightmare scenes with the baby in the house on fire), which has led several critics to say that the director has privileged visuality over the drama of his protagonist. Taking advantage of the liberties that the novel takes, Dominik undoubtedly intends to shake the viewer, to dismantle the myth of Marilyn, to bring to the surface the most sinister elements that the ermine, the diamonds and the glamor could not completely conceal, and for this he appeals to the same shot of the abortion seen from the perspective of the vagina, or to the fellatio scene that she performs for a Kennedy who at the same time talks about other women on the phone and who ejaculates watching on television scenes of catastrophism of a class B science fiction film. From subtlety to the broad brush, with high aesthetics pretensions, there go the best and weakest moments of Blonde, between cascades of tears from a woman who apparently laughed little, did not know how to take advantage of the best of her life, and who lived deceived by reading false letters from a father who never gave her a stuffed tiger.

But in the middle of all this, I insist, is Ana de Armas. And although sometimes her wigs remind me of Penélope Cruz with a platinum wig in Broken Embraces, and her accent and handling of her voice exasperate me by not going beyond the whispers that have been caricatured so many times when embodying Monroe, it costs me absolutely nothing to recognize the warmth of her performance. This is one of those roles that comes very rarely in an actress’s career, if at all. She got it by unseating Jessica Chastain and Naomi Watts, after attending three auditions. And knowing that she would face objections for her career still in formation, and even her Latino origin. More than that, there was whether she could measure up to the actresses who have stepped into Norma Jeane’s shoes before, including my favorite portrayal of that stunning woman, Michelle Williams in My Week with Marilyn. And surpassing the passion and even the vulgar chauvinism that made so many clamor for an Oscar for the Cuban, without many having even seen the film yet, I am happy to say that the leap into the void that Ana de Armas took has been worth it. She, at last, is the absolute protagonist in a piece where she can confirm not only her beauty (she was already splendid in Blade Runner 2049), but also the breadth of her acting range. Thanks to her, the infinite three hours of Blonde go by much faster, and she goes from one complicated scene to another like someone crossing a battlefield. There will be those who only bow to the moments in which she replicates Monroe when she sang Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend, or in those numerous crying scenes. There are others, such as in her first dialogue with Arthur Miller (this time Adrien Brody’s nose does not help his characterization very much), when she presents her ideas about a character, which demonstrate the young actress’s commitment to that larger-than-life role, as they say. I care little about the Oscar race (she already has strong rivals in Michelle Yeoh and Cate Blanchett, winner in Venice, where Blonde had its premiere), and what is worth noting is her growth, her dedication, and her passion for this project, which is simply undeniable.

Beyond the inconsistencies of the film, of its narrative that does not quite find a central point at specific moments, Ana de Armas has turned out to be a possible image of Norma Jeane, even when the camera insists on crudely photographing her nudity, subjecting her to those tests of fire of true Calvary: that of offering everything, absolutely everything, in exchange for an answer. Of some truth to hold on to. Of something that, from the mirror, tells us cleanly what we are, and not what we dream, no matter how hard this is.

* OnCuba reproduces this comment with the explicit authorization of its author.