Carlos Acosta is inviting professionally trained dancers to join the company he is going to form in Cuba, the country where he was born.

The future director will hold auditions on August 10 and 11, in the Fernando Alonso National School of Ballet, on the corner of Prado and Trocadero streets, Havana, at 2:30pm, local time.

The new company affiliated with Havana Dance Center, will offer contracts to a total of 12 dancers: six men and six women, who demonstrate the capacity to assume the demands of classical and contemporary dance.

In keeping with this vision, auditions will consist of classes in both dance forms, in order to measure the hopefuls’ abilities.

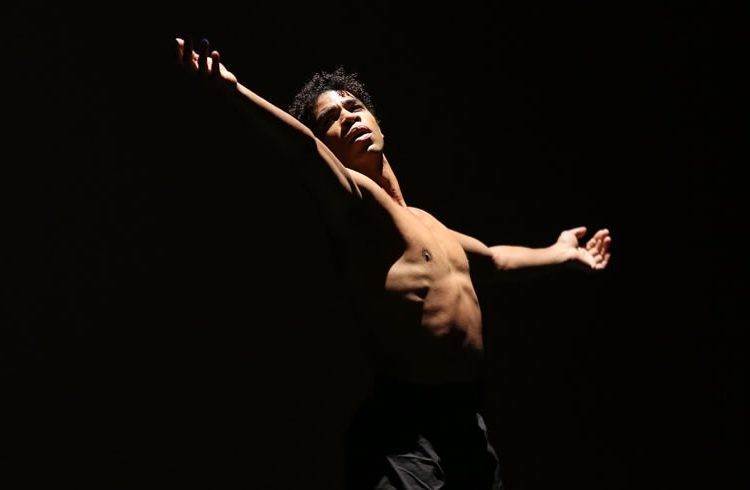

Acosta is currently preparing to retire as a classical dancer at the Royal Ballet, with his sights set on a career in contemporary dance. This year the UK’s Critics’ Circle presented him with the National Dance Award in recognition of his achievements during a lifetime devoted to dance, while his version of Don Quixote for the British company was warmly received by U.S. critics.

After enjoying the success of Don Quixote, Acosta chose to end his time with the Royal Ballet in the form of a choreographic treat, a new version of Carmen, both an aspiration and challenge considering other renowned interpretations which exude originality and charm such as that of France’s Roland Petit, Cuban Alberto Alonso and Mats Ek from Sweden. The piece is scheduled to premiere this September and will mark a watershed in the artist’s career.

No one could have predicted that he would become the only black ballet dancer to date to reach the pinnacle of world ballet and remain there. Last year he was awarded a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) by the Prince of Wales who, during the ceremony at Buckingham Palace, praised the Cuban for having become an inspiration for disadvantaged young people.

Living in the modest Havana neighborhood of Los Pinos, “Superman Acosta,” as he is now known, didn’t have many expectations at 17 years old. After a difficult start in ballet, Carlos Junior, under the instruction of maestra Ramona de Saá (Cheri), unwittingly became one of the best dancers at the school.

“I kept my expectations low, I had adapted myself to thinking that way, as a way of avoiding disappointment. Suddenly, I won the Lausana Grand Prix (Switzerland), I couldn’t believe it,” he said in a previous interview.

His first years at the school were chaotic. He was often in trouble, but his father’s determination that his son earn a degree began to bear fruit when the teenager discovered a connection between the virtue of sport and dancing, later falling in love with the art form. That is to say, the awards didn’t come easy.

“I worked hard, I wanted to be really good, I realized that if I really worked at it, I could change my future and that of my family’s,” he said.

The artist’s professional career began in 1991 in the ranks of the Cuban National Ballet (BNC). He didn’t think twice when, at 18 years old, he we was offered the role of lead dancer at the English National Ballet (ENB).

According to Acosta, he arrived in London with just his backpack and a head full of dreams. He barely understood English while the lack of rice and beans in his first months soon took its toll. The Cuban discovered other styles and schools of dance; he was soon offered the chance to be lead dancer at the Houston Ballet, and was described by the U.S. press as “a global sensation,” earning him comparisons to the world’s most celebrated male ballet dancers: Nijinski, Nureyev and Barishnikov. At the end of the 20th century, Carlos joined the London Royal Ballet, which from that point on became his home.

In the UK, the dancer received the National Critics Prize and was nominated for a Laurence Olivier Award for his debut choreography “Tocororo: Fábula cubana” (Tocororo: A Cuban Tale).

Many critics have dubbed Acosta the best dancer of his generation. In addition to his work as a performer, he has also published two books and made two film appearances.

Despite announcing his retirement, it is certain that Carlos won’t be leaving the stage for good, staying true to the belief he expressed to me one typically hot Havana afternoon: “Ballet isn’t a profession, but rather a way of life.”