It is said that someone asked for his most unusual experience. And it is also said that Guillermo Vidal replie d: “A guy threatens me with a gun and he was who cowers.” Perhaps both the answer and the question did not ever exist, or maybe they did. If this were the case, even the story of the gun could be an apocryphal anecdote. However, the fact is that that image, the one of the man undaunted by the barrel of a gun, ideally defines the literary lineage to which Vidal belonged, i.e. the one of those that never, not even for a moment, hesitated to contemplate the face of the Gorgon. Let us think for example in Dostoevsky, in Celine, in Faulkner in Arenas. It is very likely that Roberto Bolaño , confessed admirer of indomitable, wild and reckless writers, would have been fascinated by Vidal’s work, which has been awarded inside and outside Cuba.

Guillermo Vidal and Matarile, twenty years later

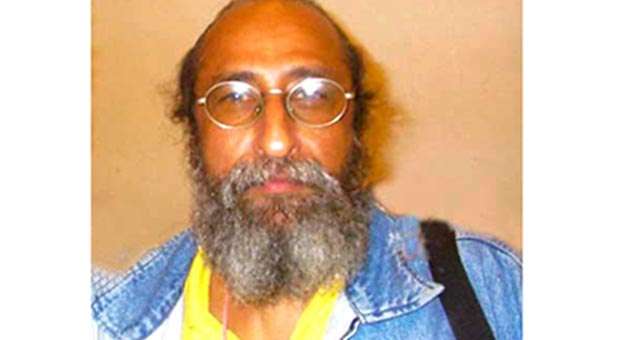

I was lucky to personally meet Guillermo Vidal (Las Tunas, 1951-2004). On the contrary, I’ve indeed read all his novels, and stories, and that, I think, is the best way to meet a writer. Most of his friends agreed that he was a guy to whom fame, that mirage that dazzles many, cared very few. In the pictures, or at least the ones I’ve seen, he appears with very long hair, always collected in a ponytail; also wears beard, which is also very long, thick, and still black, though, on his left side, it can be seen a nascent patch of gray hair, his glasses are round and large, similar to those of John Lennon or the ones of the author of 2666.

In fact, now that I see one of those photos, I tend to think that, in effect, Guillermo Vidal vaguely looks like John Lennon, and he would be rather like John if not because in his sight, the one of writer, there is a flash, or the reverse of a flash, which I have not perceived in almost any photo of the member of The Beatles. I do not speak of melancholy, insecurity, sadness, helplessness, loneliness, all of which the English man had plenty enough. No. If the pacifist John Lennon would have committed the folly of joining the army, and if after spending time in Vietnam, which by then was like saying into hell, if he would have had the dark privilege of getting out alive, his look, no doubt , would seem far more to the one of Guillermo Vidal. You may look at his eyes and suddenly certainty assaults you, or perhaps intuition, that that man, like Mr. Kurtz, has glimpsed the horror that he has looked into the abyss. Vidal, to my knowledge, did not participate in any war, but he did not need it. There are, of course, countless ways to haunt hell, to inhabit it. There are also countless ways that hell to end inhabiting us. Guillermo Vidal, maybe reluctantly, was a man inhabited by hell and was convinced that he was not the only one. This is attested by his best books, to which more than one writer has devoted praises that anyone would want for himself; praises denoting admiration, respect, although, there were not only writers, but Cuban writers, so you can presume that behind such praise there is also a shadow of envy, suspicion.

Vidal’s pious sympathy by madmen, ill persons, perverts and murderers, who abound in his stories and novels, is unquestionable. At times he allowed himself the occasional praise of the disease, specifically epilepsy- a condition he related, half serious, half joking-with genius, which, strictly speaking, is far from being new and yet must be understood, here, as a way to honor the author of Crime and Punishment, one of his teachers.

A madman indeed is the protagonist and narrator of Matarile, the first novel by Guillermo Vidal, published in 1993, twenty years ago. The character is called Toño and belongs, in a certain sense, to the lineage of Don Quixote. Toño´s madness, like the one of the Manchego Knight, is a rare form of lucidity.

Between the lucidity of both, however, a mountain stands. The madness of Don Quixote, incarnation of utopias, drives him, we would say today, wanting to make the world a better place. Toño´s madness, however, makes him lashing out at almost everything and especially against utopias, against the slightest glimmer of hope, against any doctrine of redemption. Matarile is a pessimistic, devastating, unforgiving novel, which runs through a fast-paced and fragmented monologue, not just the story of Toño, a young from out of town, but the convulsive and contradictory history of a nation convinced that future belongs to it.

But, according to Toño, future belongs exclusively to death.Everything gets disintegrated. Everything gets sick. Everything rots. Everything, sooner or later, gets corrupted.

There are writers who would not want to be remembered for his first novel such as Leonardo Padura, for example. After Matarile, however, Guillermo Vidal could have kept quiet. Luckily for us, the readers, he did not stop writing, largely, I suppose, because that was what not a few idiots would have preferred , although Vidal never cared too much what the rest of us opine, neither the going trends, nor topics in fashion. While Cuban literature pointed in one direction, he was staring elsewhere. In the middle of the special period, when a considerable number of writers were devoted to talk about the challenge posed to live in Cuba, the author of Matarile was most interested in addressing the challenge of just living.

If there had been an army comprised solely by our narrators, let’s say by narrators born after 1954, an army that would have been forcibly deprived of generals and colonels, an army that at most would have one or two captains, four or five lieutenants and a thousand soldiers, Guillermo Vidal would have not deigned to join any platoon, any squad, but would have sought a way to defect as soon as possible and walk alone out there in the open field, without responding to anyone’s orders, he would have been, probably, the most terrible of the snipers.

The copy of Matarile I own was given to me by a “friend.” For quite a while, two or three times a month, I usually go through the bookstores in Havana or, I should say, through the ones I know, in order to thicken my library or simply when I have not money, just by curiosity or masochism. I’ve never found in the library of Reina Street, or in the one of 25 and O Streets, nor in that which can also be reached by 25 Street, which is located near the Faculty of Biology, a copy of Matarile, novel of worship which, inexplicably, to my knowledge, has not yet seen its first reissue. Other works, which first editions were post Matarile-such is the case of El pájaro: pincel y tinta china, by Ena Lucía Portela- have been already reissued. Unfortunately, this novel of Vidal has been overtaken by oblivion, the relentless oblivion that Toño, the protagonist, points to all and each one of us.