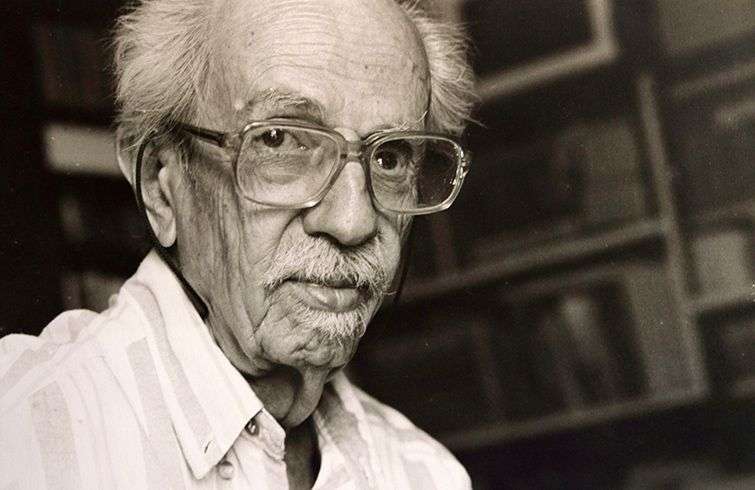

Leonel López-Nussa (Havana, 1916-2004): Draftsman, painter, engraver, illustrator, narrator, journalist and art critic. A maestro who knew how to wield in parallel the pen, the brush and the gouge, and create a family included among the most representative of the contemporary panorama of Cuban music.

Barely two years ago, in 2016, Cuba commemorated the centennial of Ele Nussa: that’s how Leonel López-Nussa signed – between the 1970s and 1980s – his witty criticisms, reviews and comments in the pages of the magazine Bohemia. His lucid, incisive and enjoyable writings are not only the testimony of what was happening on the island in terms of plastic arts – during those decades the term visual arts had just been coined -, but also in other parts of the world. His texts, of great depth, could be understood by the average reader without leaving aside the solid argument and, on occasions, a certain dose of irony and pungency. Having a high ethical sense, he always said what he thought, which is why many of his criticisms were not well-received. National Prize for Plastic Arts Pedro de Oraá has correctly said that López-Nussa’s criticisms “encouraged against all odds and for many years an almost deserted sphere of thinking in that specialty, to the point that his imprint, after he retired from journalism, is still remembered.”

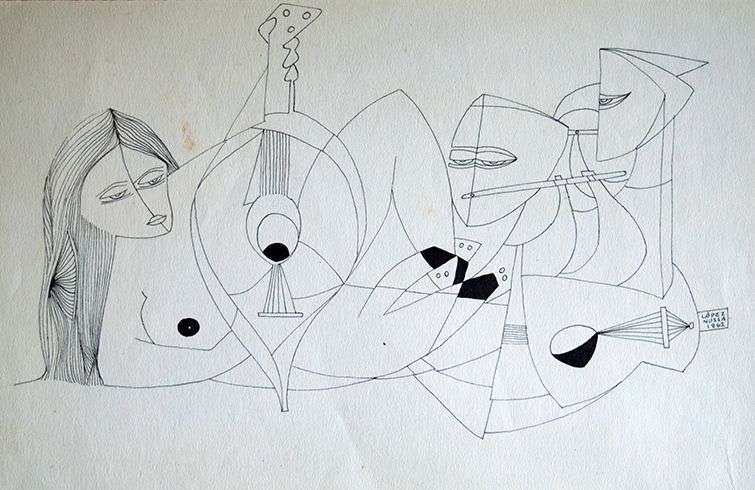

López-Nussa put drawing in a privileged place of honor. In 1964 he published El dibujo, a book in which he expressed his ideas regarding the line. That text, vital for the understanding of drawing in the development of a painter, was reprinted in 2010 by Letras Cubanas publishers.

It’s not by chance that in 1983 plastic artist and poet Fayad Jamís affirmed that “his painting, which has dealt with the most diverse subjects since those series of Mambí independence fights, passing through his innumerable musicians and his long series of homage to Picasso, is always original, fresh and beautiful. López-Nussa’s plastic work is an example of the rigor in drawing.”

In 1975 is made a very interesting series of lithographs which he titled Breve historia del magisterio en Cuba: beautiful, close and heartfelt homage to his mother – Laura Carrión -, a rural teacher who worked in the countryside in western Pinar del Río. In that series, the word climbs to the work and inserts itself comfortably – something that many other artists have done -, but López-Nussa uses the word with a marked overtone of denunciation.

Between 1974 and 1976 he increasingly focused on the world of sounds and, from this approach, two extensive series emerged: Músicas (72 pieces) and Guitarras (22 pieces), and he also conceived others – although less numerous – like Músicos cubanos, Orquestas, Orquestas de mujeres, and a great amount of drawings, notes and oil paintings of different formats, the largest was Orquesta típica, which appears in the book Memoria del siglo xx cubano.

In that decade he produced a series of lithographs called Poeta en actos, in which the word again is a perceptible protagonist. Neither did Martí’s ideas escape his eye, and from this came a series of engravings that have as support the simple verses and places Martí immersed in the Cuban countryside. The collection of Spanish proverbs is a zone also touched by the artist: stanzas and popular sayings full of grace appear accompanied by a clean line, and they are a display of the artful drawing that characterized him.

Leonel was in close contact with Mexican culture. An extensive series of works and vignettes was born from that relationship, and they assimilated popular sayings – Gato viejo, caza guayabitas -, and they incorporate the particular icons of death so well-known in that country.

Another of López-Nussa’s relations with the publishing sphere – precisely with illustration – was thanks to the magazine Signos, published by the then National Council of Culture in 1974 and headed by his great friend the writer and plastic artist Samuel Feijóo, with whom he shared the taste for the popular.

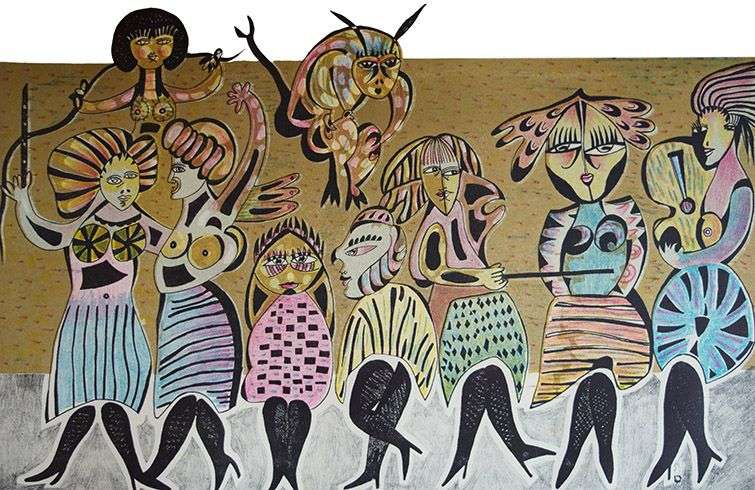

“I have always considered myself a farmer and perhaps that is why, when I met Samuel Feijóo in Havana, we became close friends,” López-Nussa said on one occasion. For many years he continued attached to the printed letter and to illustration: all that rich universe was shown in two expositions for his centennial: La pintura respetuosa, in which special emphasis was placed on the abstraction of the initial years, the new figuration, surrealism, pop art and his attraction to cubism and western art, borne out of his long periods living in Mexico, the United States and Europe. And, of course, eroticism, always present in his work (from 1950 to 2000).

The exposition La pintura respetuosa included some of his works published in diverse publications, photos, books, illustrations, personal objects, small-format drawings and works from the collection of engravings belonging to the Cuban Museum of Fine Arts.

Music, a theme exploited and explored in depth by this singular creator, for decades was the center of his work. He never abandoned the musicians or the instruments and that, I believe, is a gesture of absolute fidelity.

“He was a great music lover: he was educated in a musical context, his sister was a musician and he met my mother (Wanda Lekszycka), who played the piano, in a conservatory in the United States. He was an attentive listener, he had an excellent collection of records and in his studio, with the aid of an old record player, he enjoyed classical music and jazz. But, the Cuban popular sounds entered through the windows: that was the creative atmosphere that surrounded him. I believe that one of his merits is having interpreted the world of sound and taken it to plastic arts. Among other topics, music always had been present in his work since the early 1940s until 2000,” said Krysia López-Nussa, daughter of the creator who has been in charge of preserving, conserving and promoting her father’s works, in an interview with OnCuba.

Perhaps the iconography associated to music is among the most promoted of his pictorial work, but it must be recognized that, if something characterized this innately indispensable maestro, it was the wide-range of specialties and supports in which he moved and made incursions with true skill.