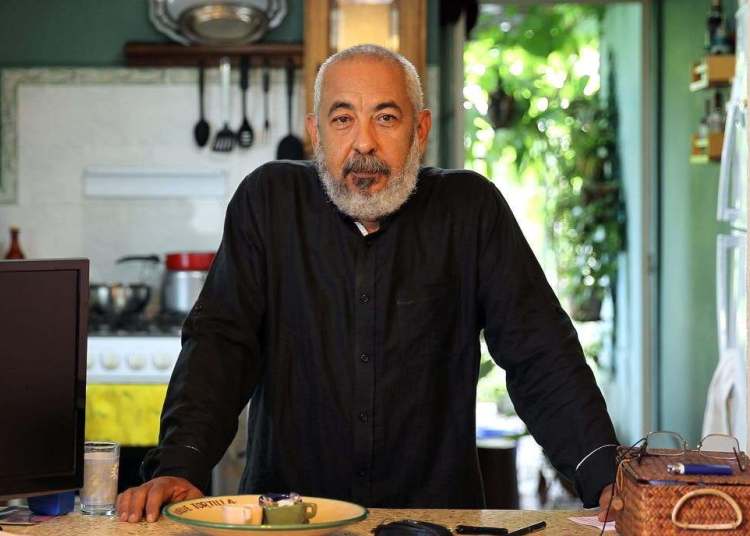

Leonardo Padura (Havana, 1955) has said that he is not the most talented of his generation, but he is the one who works the most. “And fast!” I said to myself when, a few hours after sending the questionnaire by email, I received his answers, which have the tone by which anyone intuits the typical Cuban confined to a generation that began to mark territory in the years 1980s.

Until now, his last work in bookstores was Agua por todas partes (2019), a narration that explains the secrets of his stories; but, a week ago, thanks to an interview by his wife Lucia López Coll, we learned about his new book. The genre?: novel.

Como polvo en el viento is its title and it will also be published by Tusquets, the publishing house that has allowed him to raise his voice in the world with the character of Mario Conde as a banner, and reaching summits with exciting books such as The Man Who Loved Dogs (2009).

A journalist who was punished in his beginnings, an essayist with a typewriter in the background, a daily novelist, Leonardo Padura received the Princess of Asturias award in 2015. In his acceptance speech, he indicated that he was a “stubborn man” and that “with Cuba and with my language in tow I have walked a path that is becoming long.” In the middle of that path, a stop for these eleven questions that have as their background the context of the COVID-19.

Now, when what we all have the most is time to ponder, what is the most persistent thought in Padura, not counting things like “let the quarantine and the pandemic be over,” logically?

Right now…well, I’m thinking about how to get into the novel that I want to start writing in the coming months. It will be the return of Mario Conde, whom I left behind in La transparencia del tiempo on December 17, 2014, hoping something great would happen…and it happened. Cuba and the United States were beginning to talk to reestablish diplomatic relations and…they were reestablished in 2015, President Obama visited Cuba in 2016―the Rollings Stones, Chanel, the Tampa Bay, Rihanna, the Kardashians, The Fate of the Furious were also around, everything, god―and there was a moment of joy, celebration, expectations…until January 2017, when we returned to more of the same. A frustration. Another one…and that’s what the novel would be about, in the present time, because it will have an argument in the past. About that, of the frustrations, and not only this most recent one, but others in Cuba’s historical time. And I wonder how to take that to a novel with the eyes of Mario Conde, who is never overly optimistic.

Is Como polvo en el viento a novel with more questions than answers, more answers than questions, or perhaps it is a narration that only aspires to relive essential events for your generation?

Life has more questions than answers. We spend years living on earth asking ourselves questions, some very important (does God exist?), others very carnal (can I handle that woman?) and others, pedestrian although very worrying (will the chicken come to the shopping on the corner?). And sometimes we have answers, even for the most metaphysical, and many times not…. Is exile the solution? Is it satisfactory? Why do I have to go into exile and have Spanish, French, American children? What is it to be Cuban in Cuba and what outside of Cuba? Many people have answers to those questions that run through the novel. Others don’t. In the novel there are answers and there are open questions, as in life. And by the way, there’s a line on the corner. Surely the chicken is getting in.

Due to the associations, this question is even more Dylan’s than mine: What does a Cuban writer need for his work to be understood first as an intellectual gamble and not as a political allegation, even if that proposal, as in his case, has a gravitational center in politics?

Dylan says that the answer is in the wind and Kansas replied that everything is dust in the wind. My work can be read as a political plea, without a doubt, since everything is related to politics, and more in the case of Cuba. Even in the most ethereal ivory tower, in Cuba you have politics, as you know. My intention is to look at a reality, put characters and conflicts in it, and have as a result a possible reflection of that reality, always respectful of a truth―that is not The Truth, because that, the great one, I don’t think anyone has. It’s my truth. But I always avoid turning my literature into a political plea, since I’m not a politician by trade and I’m not interested that those in the trade use my works for their use. They can do it, they do it, but that’s not my intention. I believe and want to be a chronicler of my time and experience, in that position I try to make the political substrate more evident. The other is inevitable and I don’t shy away from it.

Do you consider yourself a writer for whom reality is heavy enough to subjugate your characters?

I am a writer of reality. And that reality feeds me with stories in which I place fictional characters that closely resemble those of reality, because they are the emanation of that reality, of their learning and coexistence. Sometimes they are even real characters: Trotsky, Mercader, Heredia, Rembrandt…. The thing is that the Cuban reality is very heavy, dramatically speaking. So much so that we go over and fall into the territory of the peculiar. An example. What does it take in the world to have a car? Answer: money. In Cuba: having a lot of money. And I can continue along that line to infinity. And that excessive peculiarity is literarily dangerous, because you can fall into the temptation to explain, and literature is not for that. You must then look for balances and sometimes it is difficult. The danger of local customs is always there, lurking, and you should try to avoid it with the awareness that literature is (or should be) connotative and, moreover, have universal projections, but in realities, at least in the human consequences of those realities: fear, courage, hatred….

How did you conceive this novel, how decisive was the framework, the carpentry or whatever you call that which determines it? What moment of those years through which history passes was the most moving to relive?

This is a novel with stories that are circulating throughout 25 years. They advance in time and return to the past in search of possible reasons and truths. It is like this for each of its characters. This implies a break in linearity, a more cyclical or spiral structure, although everything begins in 1989 and ends in 2016, and things happen that have no regress, such as deaths, abandonments, deceits…although they do have reasons in the past and consequences in fate. And that was a structure that I discovered in the writing process itself. When I wrote the first chapter I had an idea of what the second would be like, and then the third…until I reached ten big chapters. They advance and go back, information is discovered and ratified. This has involved, of course, tremendous work, because after a first version I had to rewrite everything so it would fit and from there rewrite the novel many times so it would fit it well and was expressed in the best way that I’m capable of doing it. Unhurried, with passion and with a cold head. And I think that the moment that stirred me the most is just the final block of the tenth chapter: for what it implies as a perception of abandonment and loneliness, for what it can be to belong to a homeland and to see how those tremendous injustices of fate occur that take a good one and leave us here with so many bastards.

Carpentier, one of your teachers, said that whoever wants to have effective political action in America as a writer should start by having an important work. You have a work and for it important awards, what political impact have you achieved, not just in America and the world, but in your country, your city, and in Mantilla?

I think Carpentier was wrong, at least in my case and others. With others who don’t have an important work and live in a political scream, even oozing hatred, resentment, revenge (and envy at heart, or not so much). I have no political incidence, I think. If anything I have made some people think about some things. For example, when The Man Who Loved Dogs was published, I received messages from many people, mostly Cubans, most of my generation, who told me something very encouraging: the novel had helped them understand things in their lives they didn’t know or had never known. And that was the best compliment I got. If that can be called political impact, well, I’m not very clear about that.

For a narrator who writes and lives in the same point of the island, what are the challenges of feeling exiled or emigrated to then develop a story?

Exile, I have said it, many people have said it, is always dramatic, heartbreaking, and can have different consequences, as I have been able to observe. Before, there is something important I must say: if you are a bad writer, you are in insile and in exile. The same goes if you are envious, a son of a bitch, as we know there are some. Or a good person, like others. This drama of exile can be motivating or paralyzing. The second more than the first. And this is so because the writer belongs to a culture, to a linguistic norm, to a way of perceiving and living reality that are not replicable. And that affects everyone, not just writers or thinkers or artists. Giving up or being away from natural belonging is unnatural, even when so many people in the world choose mobility (which should not always be read as exile).

In Clarín you mentioned the lines there are also in your neighborhood these days. Do lines have the shape of disappointment? What disappoints you at this point in time?

Lines have the shape of need and anxiety. Every time I see that there are ten tomatoes left in the house, I say to Lucia…and the tomatoes? And so on with everything. I’m already suffering because I only have yogurt for two weeks. And then? Pure need, tremendous anxiety. And disappointment is a more elaborate, more intellectual feeling that not everyone processes or they process it the same. I am disappointed, to continue with the topic, that so many years later, tomatoes and yogurt and many other things are still a greater anxiety than the existence of a deadly virus. That’s why people line up in stores. We haven’t managed to have an economic system capable of functioning, no matter how many plans, laws, and tried projects. In a country that should be able to feed itself to the obscenest obesity. I am disappointed to see, in times of global crisis, so much human stupidity, pettiness, selfishness. Although at the same time it comforts me to see so much intelligence, solidarity, dedication. You have to be very brave to get into an infected site of death to save the infected. And there are many people capable of doing it even without being paid, or even if they pay very little, like thousands of Cuban doctors who deserve all my respect…and I think that of many people.

What lessons do you think Cubans can give the rest of the world now that each country has been, through confinement, an island threatened by economic precariousness?

World teachings? Well, I think only a Cuban would dare to ask that question to another Cuban. That’s why we are Cubans…! Well, the truth is, I don’t know. Perhaps that it is possible to live with much less than one believed one needed to live on, and then continue singing and doing what Cubans do a lot…ñakañaka! Look, I don’t think we’re going through something like another special period, even though it might be similar in some ways. And in those years the inventiveness of the people shot up and, to be closer to my territory, their artistic creation as well. Remember that it’s the time of movies like Strawberry and Chocolate or Madagascar. The moment when the Cuban novel returned to be of interest in the editorial markets. In which Cuban music produced timba and even the Buena Vista Social Club and Cuba won many Olympic medals. Necessity is the mother of invention, it is said.

The Cuban president has called for or suggested liberating the forces of production, do you think that the more conservative Cuba will change after this situation or do you think that when everything is over we’ll be the same or perhaps worse?

When speaking of liberation, by simple semantic association the word “imprisoned” comes to mind. I hope that this difficult situation that we are already in and that is only beginning, will help those who run the country to be more daring. The usual problems can’t be solved with the same solutions as always because we’ll have the usual results. Yes, it is necessary to free the country’s productive forces without fear that wealth will be generated, on the contrary, it is necessary to generate wealth. This bump may be the time of the jump. And not in a vacuum, precisely.

What makes you happy, Padura, right now and in the midst of so much bad news?

Still having yogurt! And to think that perhaps we’re coming out of the worst tunnel (there are others, of course, but this one from the pandemic seems exorcised as everything indicates that things have been done well, those who know have been listened to). And that, when I go out, I will regain the possibility of sitting down with my friends, in Cuba and in the world, and in Conde’s best style, with rum, wine and food, spending a few hours talking, even if it’s talking shit, because man cannot only live by talking serious things. At least I don’t. It also makes me happy to know that in a few months I will be presenting a new novel. That I have another in mind. That every week I receive job offers. That my mother turned 92 in the midst of this pandemic and is still there, still alive and kicking. That Lucía accompanies me and scolds me when I cross the line. That my mango trees have even allowed me to give friends bags. In short, there are many reasons to feel pessimistic, but there are also other reasons to feel satisfied, and those are the ones that you should enjoy with the people you love and with the people who deserve it. While others suffer over happiness and others’ effort, I write, I publish, I answer interviews and that makes me very, very happy.