I owe to the visit of Yoan Rivero, a young Cuban bibliophile, that these memories have been stirred up. Rummaging through my bookshelves, we found some interesting books, both because of the quality of the texts and the generous autographs of the authors. One of them is the first edition of Los días de tu vida, by Eliseo Diego, Unión publishers, 1977.

The “finding” led my sharing anecdotes in which my modest path crossed with that of the author of En la calzada de Jesús del Monte, one of the classics of Cuban poetry. Eliseo, at the same time as authority, gave off a human warmth that many times materialized in the painstaking attention when listening and in certain jaunty little lights that sparkled in his eyes. His goatee, his eternal pipe, his fine humor, made him a hybrid of an English lord and a Cuban prankster.

Being a poet must be demonstrated

I had approached him in the halls of the Union of Writers in the early 1970s, when I was joining the Hermanos Saíz Brigade. I quickly showed him some perfectly forgettable poems. He looked at my manuscript and told me: “If you let me have it for a few days, I can read it with the concentration that the case warrants. Come see me in my office next week, and we can talk there.” He treated everyone as “usted,” which in Spanish is a polite form of address.

I of course entrusted him with my complete works…until then. And I began to count the days. When I thought it was time, I dropped by one morning where he worked. He received me with a cordiality that disarmed me from the outset.

He spoke. I don’t remember how much he said, because I was in a state of ecstasy that I haven’t experienced since. When he finished giving me encouragement and suggesting readings, he let me know that what interested him most in my poems was what I had not written in them, the potentiality that made him augur (I remember that he used this verb) that I could write truly remarkable poems. What a fancy way of telling me that this was bullshit, and that what I should do was read and work more, to see if I ever managed to come up with something that wasn’t bullshit!

Anyway, I was so comradely and happy with the maestro, that I ventured to blurt out, out loud, a stream of poems I had written since our last meeting. He listened to me with the resignation of a bull grazing in the rain, and from time to time he checked his wristwatch. But I didn’t even notice. Around 11:30 in the morning he asked me: “Would you like to meet Guillén?” How could I not like it, if I had practically learned to read with the “Elegía a Jesús Menéndez,” which was one of my father’s favorite poems?

What I didn’t know is that Nicolás and Eliseo had a daily ritual. Half an hour before noon, they met in the office of the Presidency to joke and have an ice-cold vodka, as an aperitif before each one went home for lunch. In those meetings, I found out later, they joked like schoolchildren. The expansive character of Nicolás fit perfectly with the serene forms of Eliseo, who smiled while his jokester fellow laughed heartily.

Eliseo gave a few discreet taps on the door of Nicolás’s office, and from the other side he received a thunderous “come in.” We had overcome the stumbling block of Sarah, the iron secretary, and if someone got there at that time, it couldn’t be other than my guide for that day. Seeing that Eliseo was accompanied by a stranger, Guillén was not very pleasantly surprised.

“Nicolas,” Eliseo said, “I present to you a young poet.” To which the man from Camagüey responded with his proverbial grace and mental agility: “I can see that he’s young.”

I stammered two or three words of greeting and left the office terrified. Behind me were the laughter and the humorous comments.

Fray Luis de Leon

In 1975 he had entered the then Faculty of Philology. Very soon I alternated my duties as a student with work in the culture team of Juventud Rebelde. With what I didn’t know at the time, five volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica could be made (now there would be a few less). But I didn’t think so. Ignorance is bold.

In 1978 the collection of poems Los días de tu vida fell into my hands, which, to put it quickly and badly, blew my mind. Alejandro Alonso, my boss, asked me to review that book for a Sunday edition, to which I more than gladly agreed.

My very enthusiastic review, among other dalliances, advanced the risky theory that Eliseo owed a lot to Fray Luis de León. Now that I think about it, perhaps it is not entirely nonsense to say that. But at that time, I knew about Fray Luis through his poems “Al salir de la cárcel,” “Agora con la aurora se levanta” and little else.

Mid-morning on Sunday my comment appeared, Eliseo called me to thank me for having noticed his book. Bella, his wife, and Rapi, Lichi and Fefé, his children, he told me, were very happy with the review; also Cintio and Fina.… At the end, at the farewell, he blurted out: “Listen, Alex, we have to meet sometime so that you can point out the points of contact that you find between me and the Salamancan.” Needless to say, that possibility terrified me. What could I tell him if, honestly, I didn’t know how I had come to write that?

After that, every time we saw each other he reminded me that we had a pending conversation. I would get away as best I could and change the subject. I never asked him if he was really interested in my “theory” or if it was a fraternal joke on his part.

The party

It must have been in the late 1980s. A cycle dedicated to the work of Jorge Sanjinés was organized at the Cinemateca de Cuba. Now I don’t remember at the screening of which film I met Eliseo, who was sitting two or three rows behind me. It may have been Ukamau (1966), Yawar Malku (1969) or El coraje del pueblo (1971). The fact is that in the film there was a sequence of some men celebrating something around a bonfire. They were drinking chicha and they sang and danced to the melancholic sound of the quena. I think what they were playing were huaynos.

At the exit of the Charles Chaplin theater, Eliseo was waiting for me. Without further words, he told me: “What a sad way these Bolivians have fun!” And then he was lost, down 23rd street, in the night.

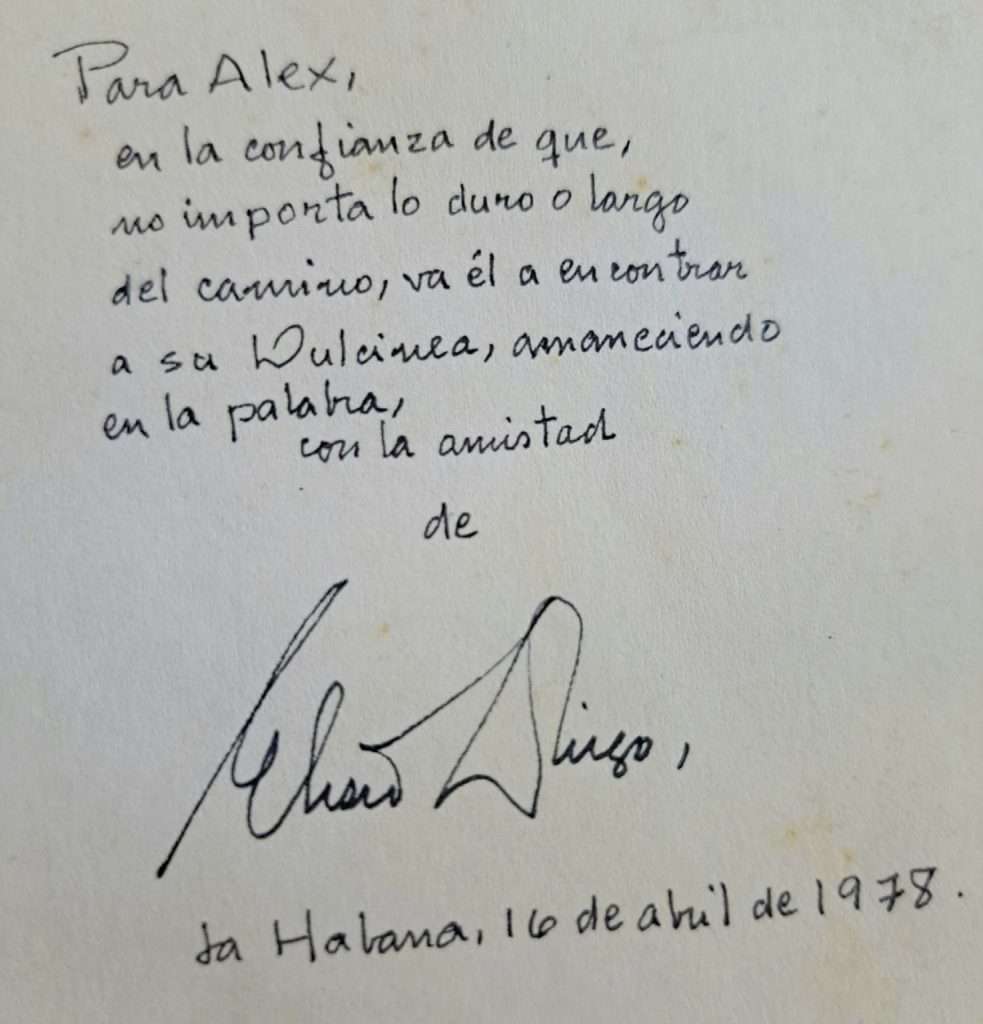

The dedication of the book that has triggered these memories says: “For Alex, trusting that, no matter how hard or long the road is, he will find his Dulcinea, dawning on the word.” Now it occurs to me to respond with a quote that, I’m sure, he would have liked. It is also from Don Quixote:

Evil signum! Evil signum! Hare runs away; greyhounds chase her: Dulcinea does not appear!