Alden González accumulated enough merits as a producer during his work with the Septeto Santiaguero. He won two Grammy Awards with the group and contributed to giving some shape to records that bear witness to the international drive and high credits of traditional Cuban music.

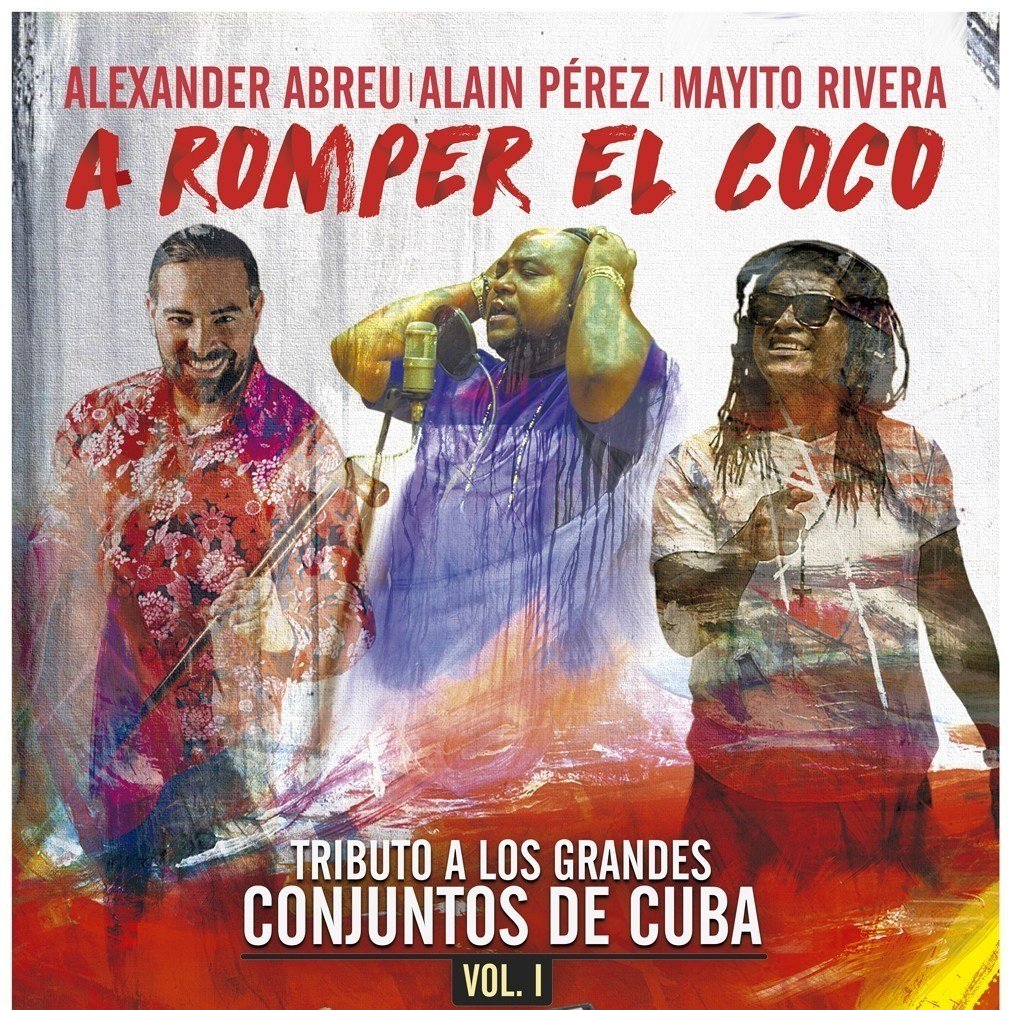

After his departure from the group he put together an ambitious album project with experienced arranger and producer Geovanis Alcántara, which will soon come out to keep root music on a steady footing in Cuba. For this they summoned three heavyweights from the island’s music scene: Mayito Rivera, Alain Pérez and Alexander Abreu.

The album A romper el coco was recorded in the Havana and Santiago de Cuba EGREM studios, and treasures 10 anthological themes of Cuban music given by the island’s sound contemporaneity and the proven experience of its producers.

“Working with those three greats of music was a big challenge. They have great knowledge about what they are doing. With the Septeto I was part of the group, but now it’s different. I have to make sure that everything I present is convincing,” says Alden in an interview with OnCuba.

“I have been friends with Alain Pérez for years, also based on the understanding of music with similar views. It was a process that I enjoyed very much. We made a good design together with the artists. It wasn’t easy but as we enjoyed it so much we didn’t see the difficulties pass. This way of working easily has a lot to do with the work of Geovanis, who is amazing as a professional.”

What is the purpose of an album like A romper el coco that rummages in the roots of traditional Cuban music, when what prevails in the market are the most commercial sounds?

In A romper el coco we are in favor of the rescue of Cuban music. There are interesting fusions like “Negro de Sociedad.” The theme was popularized by the Rumbavana group and in this version La conga de los hoyos also participates. We are talking about the participation of three notable figures as singers but who in principle are musicians, artists with superior knowledge.

On that record there is a tribute to Arsenio Rodríguez, the Matamoros group, where Benny Moré sang; to the Casino group. At that time there were different ways of doing in the format. As if there were black and white groups. In the white ones the casino was the leader and Roberto Faz and the Nelo Sosa Colonial Ensemble came from there. We also pay tribute to La Sonora Matancera, with the recording of its song “Ave María Lola,” which Carlos Argentino recorded and was very popular in its time. In Havana, people really had a great time with the Sonora Matancera.

“Me la llevo” is a tribute to Benny Moré sung by Mayito Rivera. We used the clarinets because the Matamoros group indistinctly incorporated one or two clarinets. One of the clarinetists was our Compay Segundo.

We haven’t made this album in a mimetic way, but we have thought about the consumers of this music today. Believing that we are going to win a new audience would be a bit pretentious, but we do aim to reach those who like dance music. The ways of interpreting have been spectacular, we are talking about singers with a very strong musical personality who defended different concepts.

I feel very happy with the result. It’s a record we wanted to sound as if we had remastered an acetate. That people identify with those sounds according to the frequencies they handle. It also helped that it was recorded in the emblematic Siboney Studios, in Santiago.

What do you think were the main requirements of the recording process?

We experimented a lot with sounds and instruments like the tres. Before, the unit that the tres had, the pickup, was from the electric guitar. That marked the sound of the time when Niño Rivera was in full swing. Arsenio also recorded things like that. There is a pilón rhythm by Enrique Bonne called “Que rico está esto.” At that time Pacho Alonso composed a lot for Bonne.

What Pacho Alonso con Los Bocucos had was an electric guitar and now on this record we achieved a very rich sound. The same happened with “El jamaiquino,” Niño Rivera’s master work. In 2019 we celebrated the centenary of his birth as well as that of Benny Moré.

We also wanted to play with those dates because this year also marks the 125th anniversary of Matamoros and the 105th anniversary of Roberto Faz. Sometimes those dates go unnoticed, which does not mean that someone does not remember. For example, last year it was the 90th anniversary of Pacho Alonso’s birth and I don’t think much happened. Nor did much happen with the 40 years of Son 14, one of Cuba’s major groups.

I listen to many types of music because it’s necessary to understand how today’s sounds work. If I work on an aspect of the son, I also like to hear a lot about what is happening in the salsa and jazz environment. It’s not only about the musical performance, but also the ways of communicating it.

When you talk about defending tradition, people only relate it to the old Santiago trova and the son. It’s about all Cuban music, from timba to the most recent expressions of our popular music. The new generations don’t understand that it’s impossible to exist today without yesterday; little is looked at the past. That’s why we formed a team to highlight the Cuban tradition based on groups, the format that has contributed the most to the development of dance music today.

The musical base was recorded in Santiago because this city is a kind of reservoir of tradition. The DNA of musicians is always in favor of preserving the sound accent and the more traditional Cuban music. In the east, from Camaguey to Santiago, there is a different way of thinking the son. That has to do with ways of accentuating the low frequencies. The bass player thinks the son differently.

In Santiago there are many groups playing repertoire that we can call traditional, but it isn’t originally from the east. The way of playing the bass, the tumbaos, have much preponderance in the definition of those genres. In Santiago an effort was always made for the bass to be more in favor of stability and a little less in favor of virtuosity, which later developed in the timba.

Did your passage through the Septeto Santiaguero have any influence on the recording of this album?

When I was in the Septeto Santiaguero we toured with “Tiburón” Morales, with whom we reaffirmed the potential of Cuban music. Exchanging with “Tiburón,” who was a fundamental part of Son 14, is normal for people in Santiago de Cuba. But what struck me the most was when we were staying at a hotel in Havana and there was the Camagüey soccer team and the 20 year olds or younger approached him to take photos or greet him.

That happened despite the fact that “Tiburón” doesn’t appear on television or radio. That young people feel admiration for his music means that not everything is lost despite the fact that our promotion of Cuban music in the media is very bad. When we shared a concert with him in Venezuela, it was also great, because people came with anthological records of Son 14 for him to autograph.

Sometimes we think that whoever defends the son is not defending Cimafunk. And that posture is not correct. Everything must be defended to make Cuba a heterogeneous country in terms of music, where the public can choose. The United States, for example, is a country where people can listen to all kinds of music, as in Spain or Colombia.

But the first thing that has to be defended is the roots, the origins. That is precisely why we made this album, which is a tribute to Cuba’s major groups.

How have you perceived so far the path traveled by the album?

We have managed to have a high level of sales in the digital field, but I think this album should focus mainly on a national impact. It isn’t as complex to have resonance in the nearest markets as it is in ours.

Now we are in the process of consolidating the project. I am convinced that based on the official launch many things can happen with the disc. That people get to know it in Cuba would be glorious for me. What we achieved internationally with the Septeto Santiaguero was because we first managed to have recognition in our country. Those who thought that we did our job thinking about the Grammy are wrong, because our intention was always to have an impact on Cuba.

When I finished with the Septeto I immediately started looking for what I was going to do. Research work fascinates me as well as listening to a lot of music for that purpose. Also, working with unpublished material is very comforting to me. I enjoy it very much. That is why the idea of this album also arises, which was born exactly after the rupture with the Septeto Santiaguero.

You recently posted a series of opinions about Santiago’s carnivals on Facebook. Could you explain those arguments?

I find what happened with Santiago’s carnivals was shameful. I am not a detractor of urban music, I have even produced records of its exponents in Santiago. I did a job I feel very proud of when I merged Santiago and Jamaican urban artists. I have nothing against any genre, but I don’t support the national soundtrack being polarized.

Then it cannot be that only the toughest reggaeton is promoted at the carnival. Cuban and international urban music have good exponents, but the carnival has been disastrous. Polarization is killing us, as well as the lack of sensitivity of many who should channel that. You have to have more sense of belonging with all the Cuban music.

It might be thought that from the worldwide impact of the Buena Vista Social Club, more traditional Cuban music is promoted in the field of national tourism…

I think it hasn’t been that way. Tourism should be the justification for Cuban music to be more reflected especially in the hotel sector. But when you go to a hotel you realize that they put “Negrito,” “Cokito” and “Manu Manu” or Harrison and other exponents of urban music.

The relationship between Cuban music and tourism could really be healthier. I still feel that there is a lack of sensitivity and knowledge when it comes to channeling musical contents. In the hotels only the music that DJs like is played and generally they prefer anything except for Adalberto Álvarez, Issac Delgado or Paulo F.G. And let’s not talk about Son 14 or the Old Santiago Trova. The Buena Vista… may continue to operate outside of Cuba, but in Cuban hotels, what is put on is something else.