Finding Esperanza Spalding walking along the Prado Promenade close to the Capitol Building; bumping into Marcus Miller taking pictures on a small street of Centro Habana; being in front of Quincy Jones sharing the details of the sound track of The Color Purple; witnessing how Cameroon bassist Richard Bona built his personal and tremendous version of “Caravan” with Marcus Miller on the bass and the wonderful Cubans Osmany Paredes on the piano and Denis Hernández on the trumpet before the frenzied and crowded Guanabacoa Amphitheater; attending the incredible meeting of Yissy García’s drums with Spalding’s bass and voice; finding out that violinist Regina Carter was giving an interpretation workshop in the Higher Institute of Art; or running into Chucho Valdés walking through Old Havana with Gonzalo Rubalcaba. All this and probably much more could have happened to you during the last week of April in a Havana overflowing with jazz and jazz musicians.

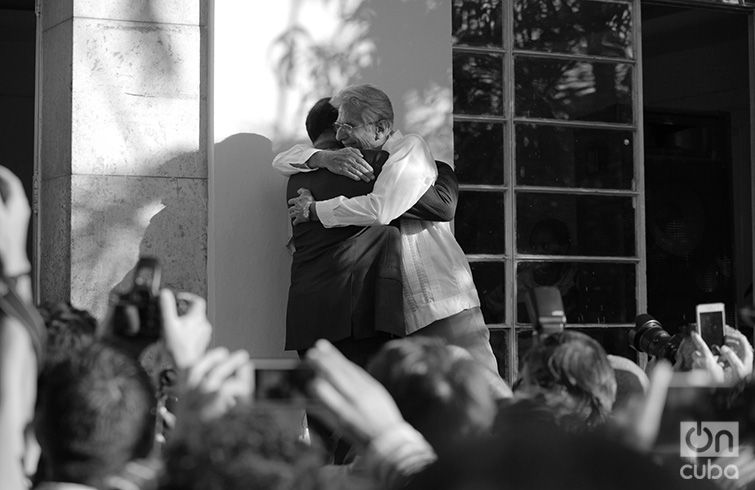

Marcus Miller, Quincy Jones and Richard Bona after Esperanza Spalding’s concert in the Guanabacoa Amphitheater. April 28, 2017. Photo: Gabriel Guerra Bianchini.

Wanting to be everywhere at once it was difficult to decide on which option I would choose, faced by the variety of jams, concerts and meetings, with the handicap that the general program did not have the deserved publicity. Even so, all the sites filled up, since the Cuban “voice mail” was working: if the jazz fans were able to mobilize, attend, enjoy and even interact with their idols, music students and Cuban musicians in general were, luckily, the most favored in that direct contact with artists who, in many cases, are their icons and paradigms. A real lucky streak that these times have brought, unknown to those who came before them.

Several days will have to go by to be able to take in the perceptions and emotions that this week brought us on the occasion of International Jazz Day, established by UNESCO, and the selection of Havana to celebrate the global concert, and above all, the evening of Sunday April 30, to which we who love jazz got to with a mixture of incredulous excitement and explicit joy.

A sober design of lights over the stage announced a concert was about to begin, a concert that could present itself as difficult for the real International all-stars that had to make it come true. But the certainty that that would be something very big immediately filled the auditorium when Oscar Valdés, the legendary percussionist and singer of Irakere, sang to Changó with his batá drums in an opening that immediately took us, it could be no other way, to the mythical “Manteca,” by Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie, backed by a band directed by Cuban Emilio Vega.

That’s how the concert for International Jazz Day began in Havana, bringing together on the stage of the Alicia Alonso Grand Theater of Havana more than 50 musicians from Cuba, the United States, Brazil, Japan, Mexico, Korea, Lebanon, France, Cameroon, Germany, China, Russia, Italy and Tunisia.

The program coordinated with very good sense diverse styles and aspects in Jazz and the contributions of different parts of the world to the genre, as a way of reaffirming the universal sense that its intrinsic freedom endorses. It was demonstrated that jazz is the language of music with which we can all understand each other, beyond languages, dialects, customs and ways of thinking and acting.

That Sunday our bodies and our senses were open to receive all the excellent music that from the freedom of jazz those musicians – ours and those who came – and the organizers of this meeting of so many nations in jazz had been promised to us and had come true.

Among so much excellence, what especially stayed with me are the intimist and masterful piano of Harold López-Nussa when accompanying the not less grandiose Cassandra Wilson; the tremendous solos of Julito Padrón in a string of metals where everybody was a super star; the incredible voice of Esperanza Spalding subjugating the double bass to the rigor of her extraordinary sensitivity and talent; the performance of Youn Sun Nah in his personal style of dealing with “Bésame mucho”; Marcus Miller’s bass, like that, with no adjectives; the extraordinary version on two pianos of the classical “Blue Monk,” where Chucho Valdés and Gonzalo Rubalcaba merge in a well-known mastery and speak to the great Thelonius of new readings and silences in his famous theme, presenting him and us with an execution that is already memorable.

It was evident how much the musicians enjoyed themselves on the stage and how much this was influenced by the magical atmosphere and the good vibe of the preceding days. I ask myself what would have happened if all the average Cuban jazz fans, who looked for a way to enter the theater, to find an invitation, to buy a hypothetical ticket to celebrate International Jazz Day, would have been able to have access to the Alicia Alonso Grand Theater. They would have undoubtedly filled several of the seats that were left empty – very visible in the general planes of the TV broadcast – because those lucky ones who got an invitation did not attend, and an option to cover them was not coordinated.

The warmth, the enthusiasm, the knowledge and the unbiased intuition of those who usually enjoy and listen to jazz would have shaken the theater with a much more organic and emotive musician-public interaction, and they would have contributed the final touch to the excellence of that Havana evening. Fans – and much less of jazz – cannot be imitated or replaced.

I couldn’t stop myself from thinking all the time: Leonardo Acosta would have really enjoyed all this!