Theater is about rooting out life, taking life miseries and representing them with strong voices and made-up faces. From the hardest life experiences emerge texts about pain, resignation, ridicule and fear.

Juan Carlos Cremata is aware of that. He knows people enjoy listening to themselves in the voices of actors because that makes them feel not so lonely. After El Malentendido and Sleep and NuestroPueblito, Cremata staged La hijastra, by Cuban playwright Rogelio Orizondo, so that people would actually listen to themselves; but we all know what happens when life starts complaining at the top of its voice: people got offended by the unpolished reality represented, so La hijastra didn’t run for long over the stage.

Today, El Ingenio brings Todo x uno to the Adolfo LLauradó Theater. This piece is made up of four monologues by Elio Fidel LópezVeláz, in a version by Cremata, where once again life is the main character in the play. «El mundo sin ellos», «El tiempo lo puede todo», «Ha muerto un héroe» and «Homenaje» are little stories, which, individually, “display an endless universo claiming for love, understanding, mostly with those people usually underestimated”. The four plots eventually mix: Pupi is Cristina’s retarded grandson; Cristina is neighbor with El Rata, who is La China’s brother in law.

Cristina (Maridelmis Marín), all of the sudden feels an urge for living life, alcohol, ice, men and life. Mainly after her husband left her and went away with Helena, la Troyana, and then returned to live the rest of his life with her. Not together but in the same house. Cristina has to take him in for her children, so she carries this burden on her shoulders, enduring her children’s conditions and the stupid theory of now is her children’s time to live their life, not hers. However, this is not the reason why Cristina decided to take care of Pupi. She did it because she was tired of seeing him on a corner of his cradle, all dirty and alone, even though he could say his name already.

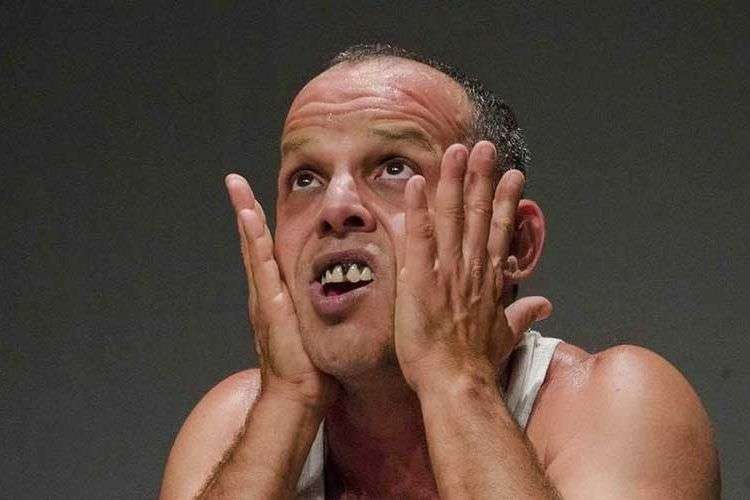

The first two monologues prepare the scene. The performances are convincing but they don’t fascinate the audience. They represent two characters who cry out loud their unhappiness, from the stench of a room comprising Pupi’s whole innocence and his vision of the world, or from their anxiety while watching the ice in their drinks melt. The third monologue, «Ha muerto un héroe», interpreted by Carlos Estévez (El Rata), is neither fascinating nor convincing and it doesn’t transcend. It is a transition between Cristina and, perhaps, the most interesting story, of the play.

La China watches her underwear in the roof of the building as her grandmother had taught her, and tells her story while rubbing hard her bra straps. La China hates her mother and hates showing off her breasts at the road for making a living. She sleeps with anyone, but mostly with el Tata, at the water tank in the boarding school, that’s the only thing she recalls, prior to Alberto, of course. Alberto is the nicest and cleanest man she is ever met. Even so, she doesn’t want to have a family with him. It is enough for her with the child she abandoned for not being able to feed him, so she got on a train which led her to Alberto and his brother el Tata, who is constantly spying on them, something that she enjoys, or at list she doesn’t dislike, which is more or less the same. It is necessary to highlight that Sheila Roche, in La China, is more than a few lines where her voice involuntarily fails. She is the living image of degradation, even with the beauty still breathing between so much pain and the past who is threatening with eating her alive.

The stories, which are no longer four but an indissoluble mix of the characters’ unhappiness, fulfill the audience expectations. Cremata, in off-voice, invites the public to reflect or to make free interpretations of the play with moderation, in order to avoid “another media campaign against the theater group”. His voice is shut down just in time for giving way to life, which once again settles on the stage.