You cannot understand Cuba without the African heritage. Its beliefs and legacy permeate Cuban society at all levels.” This is what the renowned Spanish photographer Nuria López expressed at the recent inauguration of her exhibition La larga travesía (The Long Journey), at the headquarters of the Spanish Embassy in Havana. The presence and relevance of the African in the island identity have been addressed by the artist, who provides a visual reflection on that blood, cultural and historical legacy, about which fundamental authors of the country’s social sciences have written, beginning with Fernando Ortiz and then by more recent scholars.

Miguel Barnet, ethnologist, follower of Ortiz’s footprint and author of that classic on the subject, Biography of a Runaway Slave, considers that, on a religious and cultural level, the different African religions have contributed a determining mythical wealth to the culture of Cubans: “In Cuba the patterns of African mythology, especially that of Yoruba or Lucumí origin, as we popularly call it, have served to interpret and determine political events of great importance. The common man, not just the religious man, but the profane man, has absorbed these mythical elements and made them his own.” Another highly recognized specialist, Jesús Guanche, in several of his books also highlights the weight of Africanness in Cuban identity. Let’s say that it is something out of the question in scientific and sociological terms.

Myths, music, dances, costumes, deities, customs, rituals and other constituent elements of Cuban identity were hybridized over five centuries in Cuba, since the first blacks arrived in 1510, brought by Diego Velázquez, followed by an unstoppable arrival motivated by the huge profits from the slave trade from Africa to the Caribbean. Disappeared almost to the point of extinction (but not extinct), the Cuban Amerindians gave way to the Africans, who quickly began to interbreed with the Spanish, the Tainos and the Chinese (also brought as domestic staff), resulting in what is today Cuban society from the point of view of its culture and skin color.

In La larga travesía, Nuria López approaches the topic from the iconic perspective, to make us understand that this visual perspective is as relevant as the theoretical one. She is right, especially in today’s world, where the visual has become a determining factor in understanding postmodern or current culture. In island photography, the racial theme has had important cultivators, such as René Peña, María Eugenia Haya (Marucha), Ramón Pacheco, Juan Carlos Alom, Jorge Luis Pupo and others.

No less important at the time were the photographic essays that Alberto Díaz made in the 1960s, with Korda and Roberto Salas, with Bembé and El último cabildo de Yemayá, respectively, on aspects of Afro-Cuban religiosity in the first years of the Revolution.

The truth is that blacks were never a foreground element in island photography; the change occurred in the 1980s. Previously, they were confined to a grotesque image of low-level folklore, at best. Obviously, this reduction or displacement, today we would say cancellation, is linked to the features of racial discrimination that always existed in Cuba and that, after years of Revolution, persist.

Cuban photography has been dealing with the issue since the aforementioned rupture. It is striking that, in 2004, two art exhibitions that addressed racial issues both in the United States (Only Skin Deep, in New York) and in Cuba (Labores domésticas, in Havana) converged in time. An attempt was made to demonstrate with these samples, separately, and in which photography had an important weight, that manifestations of racism continued to persist in both societies and continued to affect visual culture and the correct understanding of identity.

In other words, instead of recording the vicissitudes of racial groups, an attempt was made to prove that photography contributes, in a very important way, to producing race as a visual fact. The present exhibition by Nuria López, La larga travesía, comes to insist on the issue, but from an identity and cultural angle.

The exhibition that Nuria López brought to Havana had a splendid opening accompanied by Afro-Cuban dances and music displayed on the wide and airy terrace of the Spanish diplomatic headquarters in Havana. There the artist explained that since 1997 she has been coming intermittently to Cuba, that she irremediably fell in love with its people and culture and that the theme of our identity absorbed her to the point of dedicating around six years to constructing La larga travesía.

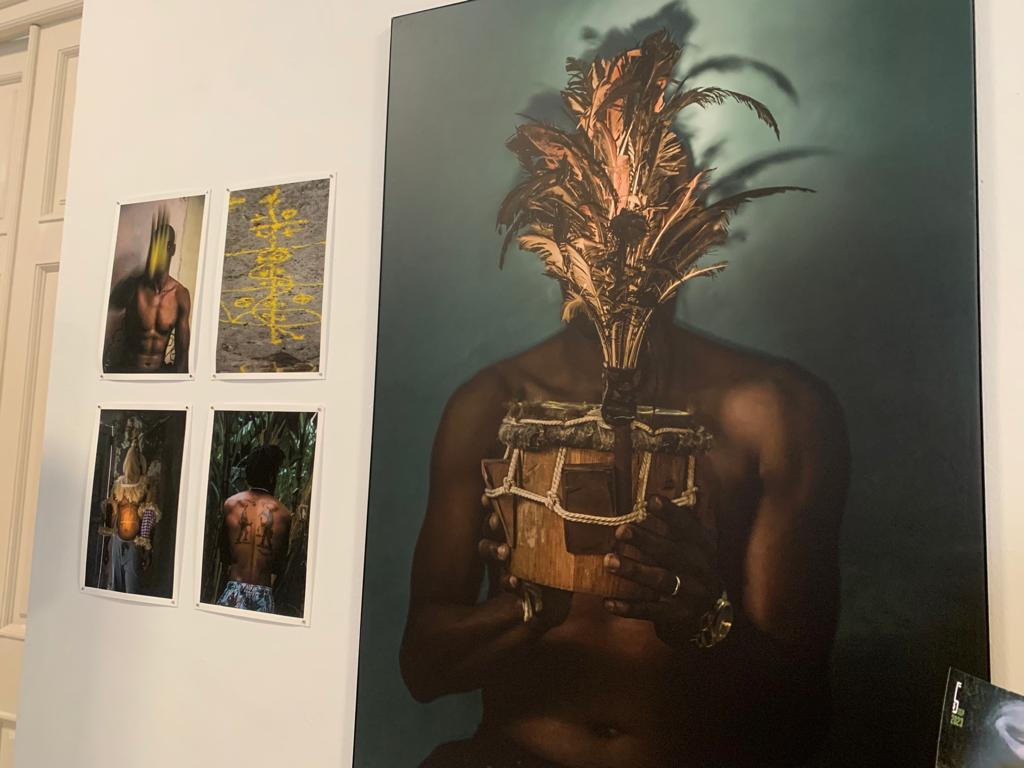

The photographs in this exhibition are divided into sections but have an evident uniqueness. “The dream of the orishas / Odù,” “The Abakuá Secret Society” and “Black Pride,” are some of the subdivisions in which the images were presented, with a high-quality print, displayed throughout the space of the third floor of the diplomatic headquarters.

“The Dream of the Orishas” is a photographic work that documents religious beliefs and practices of African origin: Regla de Ocha-Ifá and Regla de Palo Monte. “Odù” is the force of origins, the great mother of àjé (feminine force). It is the primary jar or womb of creation and is a photographic work that explores the magical universe of ancestral beliefs that connect with the land and the natural elements that African slaves brought to Cuba. “The Abakuá Secret Society” tells about this religious association in Cuba, the only one of its kind on the American continent, almost two hundred years old.

As is known, it is a brotherhood exclusively for men where its members are instructed in a model of traditional hegemonic masculinity. “Black Pride,” for its part, is a photographic work that emphasizes the manifestations of affirmation by African descendants that are currently taking place in Cuba from different social and artistic sectors. Regarding this topical topic, the artist says in her author’s note: “In this work I have been interested in giving visibility to female rappers who have a discourse of feminist and anti-racist empowerment, as well as people who show their afro hair to vindicate their identity and the entrepreneurship movement linked to Afro aesthetics.”

I want to draw attention to the staging of many of the images taken by Nuria López, as it is one of the most interesting characteristics of the photographic essay. In their composition, she tries to isolate the central object of her discourse and thus strip it of secondary issues or that may cause some distraction, which seems to me to be a very effective visual strategy. A video with a greater amount of iconographic information was projected on a medium format screen and a local actress recited a text alluding to the theme of the exhibition.

I met Nuria López on one of her many trips to Cuba, about ten years ago, she came that time with the purpose of photographing artists and intellectuals of the country and we began a friendship facilitated by a common friend, from Valencia. In our conversations, we discussed the topic of Cuban photography and others that interested her. It is very significant to me that she has created this exhibition so focused on folklore and anthropology, avoiding the tourist and commercial approaches that have been so widespread in recent years.

La larga travesía is a serious artistic immersion in a cardinal theme of Cuban nationality. It will be open at the Spanish Embassy in Havana until November 5 and, to visit it, those interested must make a reservation in advance with the institution.

The quality of the images, the author’s knowledge of the subject and her indisputable talent have been legitimized with this excellent proposal. The exhibition was complemented by a discussion on the photographic essay and its cultural connotations, which was attended, along with the artist, by two specialists on the subject: Dr. Ramón Torres, deputy director of the Cuban Institute of Anthropology, and the master Inaury Portuondo, main specialist of the Casa de África Museum, belonging to the Office of the City of Havana Historian.

When: Until November 5.

Where: Embassy of Spain in Cuba, Calle Cárcel Nº 51 corner of Zulueta, Old Havana City of Havana.

How much: Free, with prior coordination with the Embassy.