Peter Turnley, a photographer who worked for important publications such as The New Yorker, LIFE, National Geographic and Newsweek, is the first American artist to exhibit in the Museum of Fine Arts in Havana in over 50 years.

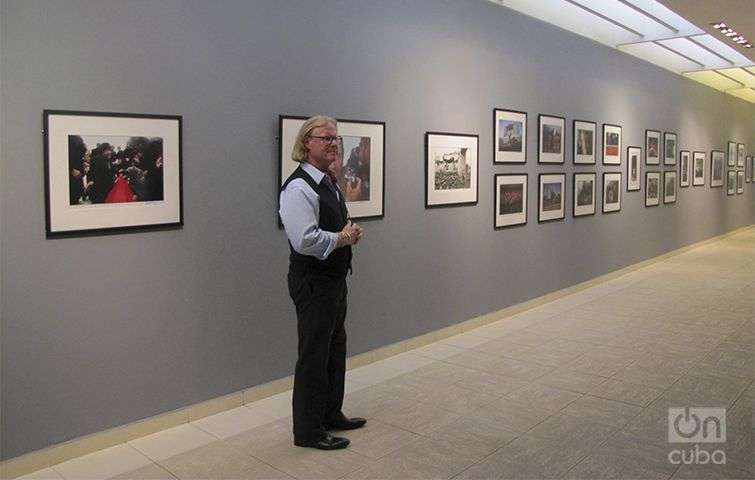

The show “Moments of the human condition” is a retrospective of his work, which, in 130 photographs, covers his experiences in his travels around 90 countries.

Moreover, this is the first time that an American photographer has put on a personal exhibition since the museum was founded in 1913.

His work includes images of the fall of the Berlin wall and the revolutions in Eastern Europe, the famine in Somalia, catastrophes and the majority of the military conflicts of recent years.

However, when trying to define himself, Turnley sees himself as a street photographer, of everyday people and their daily life. He is interested in exploring the universal element of the human condition, in places where it suffers due to injustices, but also in sweet and poetic moments where it inspires.

Turnley arrived to the island for the first time in 1989, in a trip with Mikhail Gorbachev. Since then he has continually returned, and in the last four years alone, over 20 times.

“The photographs that I have taken in Cuba during the last 30 years are a reflexion of what I have seen and felt when I walk around Havana and Cuba. The thing that impressed me the most is the power of the Cuban spirit, which seems in essence elegant, happy, vibrant, persevering, full of hope and determination, always with an idea of the future,” says Peter Turnley in an exclusive interview for OnCuba.

There is nothing more exciting for a photographer than having the impression that they’re learning something from watching people. Every day that I’ve been in Havana I’ve had the impression of learning from people, because I see them showing love not only to themselves but also to life in general, the sensation of not living individually but with everyone else, as part of a collective.

“This feeling of brotherhood that I feel is my inspiration, and it makes me feel at home.”

How would you describe the essence of Cuban identity in one photograph?

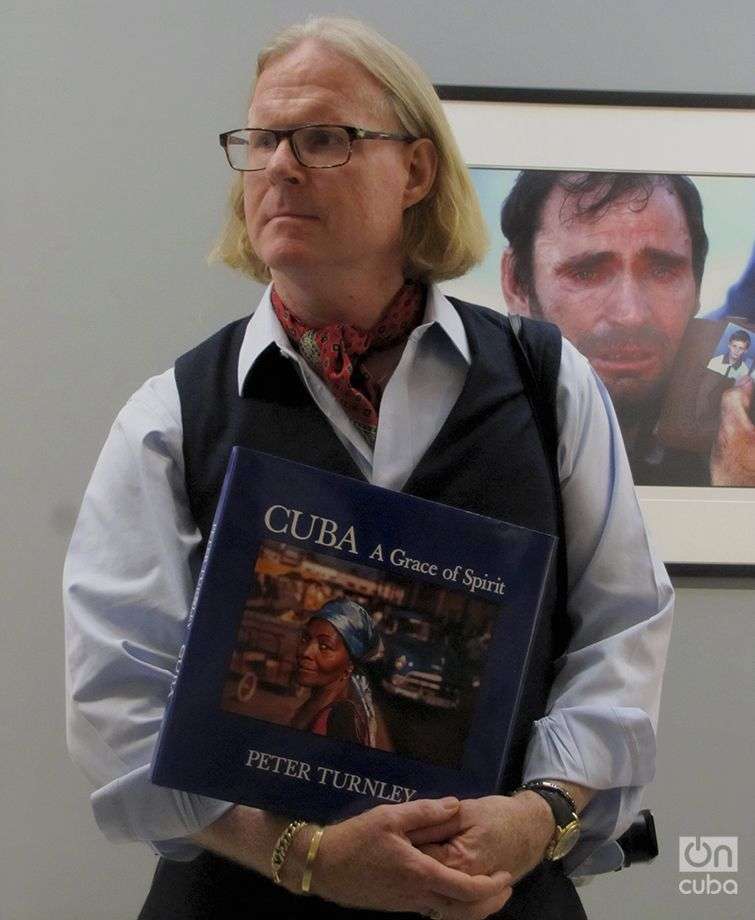

My book Cuba: a grace of sprit which has 130 photographs. I don’t believe that it is essential to express everything in just one shot, but rather I like the idea of using a collection of photos to create a great story.

I often think that there is this really powerful and inspiring moment when you make eye contact with another person. And when I make eye contact with a Cuban I have the sensation of being welcomed, I feel like they want to share their life and their joie-de-vie with me. When they see that I like and appreciate what they are offering me then there is a sort of celebration.

What characters and topics have captivated you the most over the last 30 years?

In many ways, more removed from this moment of change in which Cuba is living today, what has always interested me is the day to day, life in the streets. I think that the Cuban spirit transcends politics, and change. However, there is a constant in the dynamic of this spirit that is marked by elegance and happiness.

From a lot of them, the photograph of the mother breast-feeding her child is one of my favourites. One day I went into La Merced Church in Old Havana, and there was a young woman sat with her child in her arms. In that moment she looked at me and we didn’t need to say a word. Without talking I was able to ask her permission to take the photo. And that has been one of the most beautiful moments of my life. The baby was only 10 days old. There was something really spiritual in that experience. The mother and her child came to the opening of my exhibition in the Fine Arts Museum on November 13th.

You have witnessed conflicts and difficult moments all around the world over the last 40 years. What photo would you prefer to forget, or to not have taken?

There are many realities that I would like to forget. I have seen the most beautiful and the most terrible of life. Some of these moments that will always be with me are seeing people starve to death in the famine during the civil war in Somalia in 1992, the result of the genocide in Ruanda or the moment of conflict in Iraq, Chechnya, and also Bosnia and Afghanistan. I would prefer to forget many of the hardest moments in the wars which I have seen. But I can’t. And I also think we should not forget them. I think that photography is very important because I can give a voice to people who do not have one.

Is that why you take photographs?

Yes. For me photography is an opportunity for me to speak and to allow other people to express themselves.

You haver also photographed leaders such as Nelson Mandela, Fidel Castro and Barack Obama. How would you describe the experience of taking these people’s photographs?

Over the fourty years I have photographed everyday people and also many global leaders. I had the opportunity to photograph those you mention and also others like Clinton, Mohamed Alí, Pope John Paul the Second, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, many people who have made important contributions to defend the realities of our world.

But when I photograph famous people with a lot of power, the thing that interests me the most is not showing what makes them famous but what makes them human. I always look for the human being, the thing that reflects what they really are.

I was there at the swearing in of Nelson Mandela, in South Africa in 1994. And at the end of the ceremony there was a line of international leaders, who were waiting for their cars to pick them up. Then I saw Fidel, I walked up to him, introduced myself, we shook hands, and I asked him if I could take a photograph. He was generous and friendly. I feel very proud of having photographed him.

What advice do you have for young people who are starting out in photography?

That they should try to learn as much about life as about good photography technique.