As the anniversary of President Obama’s Dec. 17 historic breakthrough on relations with Cuba approaches, Joe Biden’s incoming administration has the opportunity to revive the successful détente that, as vice president, Biden endorsed and supported. As president, however, Biden will face fierce political pressure to demand quid pro quos from Cuba’s leaders in return for lifting the punitive sanctions that Trump imposed over the last four years in his obsessive quest to sabotage his predecessor’s signature foreign policy achievement.

But the reciprocity approach is a recipe for failure — as the opponents of normalizing relations with Cuba know perfectly well. As Biden and his foreign policy team confront the political crosswinds that any positive change in U.S. policy toward Cuba inevitably brings, it is important to recall how President Obama successfully opened what he called “a new chapter” in U.S.-Cuba relations that advanced U.S. interests as well as those of the Cuban people.

Obama’s policy of “positive engagement” was in place just two years before the Trump administration began to dismantle it. “I am canceling the last administration’s completely one-sided deal with Cuba,” Trump announced in June 2017, claiming, falsely, that the U.S. had gotten nothing in return for normalizing relations.

Over the last several years, his administration has indeed cancelled or reversed virtually every major component of Obama’s policy. Obama used executive authority to expand freedom of travel to Cuba; Trump has made travel almost impossible by canceling people-to-people licenses, cultural exchanges, and commercial air service, and by prohibiting U.S. residents from staying in Cuban hotels. Obama uncapped family remittances; Trump has re-capped them and made it almost impossible for Cuban-Americans to transfer funds to their relatives on the island. Obama gave U.S. companies licenses to operate in Cuba; Trump rescinded them. Obama restored full diplomatic relations and fully staffed the embassy and consulate in Havana; Trump reduced the embassy to a skeletal staff and closed the consulate.

Moreover, the diplomatic civility Obama adopted in dealing with the Cuban government has been replaced by the same imperial-minded bullying that defined six decades of futile U.S. efforts to overthrow the Cuban revolution. Trump has repeatedly demanded that Cuba change its system of governance and abandon its support for the embattled Maduro regime in Venezuela, or face escalating economic sanctions designed to starve it into submission. Cuba’s leaders have rejected this attempt at diplomatic extortion just like they rejected Jimmy Carter’s demand that they get out of Africa, Ronald Reagan’s demand that they get out of Central America, and George W. Bush’s demand that they remake Cuba in the image of the United States.

Yet opponents of better relations with Cuba, such as Sen. Marco Rubio, are already urging Biden to “follow in the footsteps of President Trump” rather than “return to the failed Obama administration policy of rewarding Raúl Castro and Miguel Díaz-Canel … for decades of repressive behavior.” Republicans will undoubtedly demand that Biden make ending Cuba’s ties to Venezuela a pre-condition for any shift away from Trump’s punitive policies. Biden may be tempted to give himself some political cover by adopting an incremental approach to engagement, calling for Cuba to release political prisoners and liberalize its regime in return for restoring a full policy of engagement. That would be a mistake.

As we document in our book, “Back Channel to Cuba,” the history of negotiations between Washington and Havana demonstrates that Cuba’s leaders resolutely oppose preconditions for negotiating better relations and summarily reject demands for concessions involving their internal affairs or foreign policy — even when U.S. officials put ending the onerous economic embargo on the negotiating table. Biden’s predecessors tried the quid pro quo approach with Cuba — repeatedly — and failed every time.

In secret talks with the Cubans in 1975, Henry Kissinger proposed a “package deal” of discrete, reciprocal steps that would lead to full normalization of relations. But when Fidel Castro sent Cuban troops to aid the anti-colonial struggle in Angola and Ronald Reagan blasted Kissinger and President Gerald Ford for being soft on Cuba, Kissinger broke off the talks.

Jimmy Carter also tried an incremental approach. Soon after his inauguration, he issued a secret presidential directive to negotiate the normalization of relations “through reciprocal and sequential steps.” But a series of secret negotiating sessions between U.S. and Cuban officials, including Castro himself, stalled on Carter’s demand that Cuba withdraw its troops from Africa before the Washington would lift the embargo. “Perhaps it is idealistic of me,” Castro told U.S. negotiators, “but I never accepted the universal prerogatives of the United States” to dictate how smaller countries conduct their foreign policy.

Bill Clinton defined his quid pro quo strategy as “calibrated response.” Washington would respond proportionally to incremental positive gestures by Cuba. But congressional enemies of better relations mobilized to undercut Clinton’s ability to act, and the administration’s gradualism was overtaken by destabilizing events such as the balsero immigration crisis in 1994 and the shoot-down of the Brothers to the Rescue planes in early 1996.

President Obama understood the lessons of this history. But he also believed that by making a long-term investment in engagement rather than demanding immediate returns, his administration could advance a multitude of U.S. interests and create an environment that would encourage positive change in Cuba. His decision to take unilateral, sweeping steps to normalize diplomatic relations and open the door to economic and cultural interaction proved critical to the success of his Cuba policy initiative, short-lived as it was.

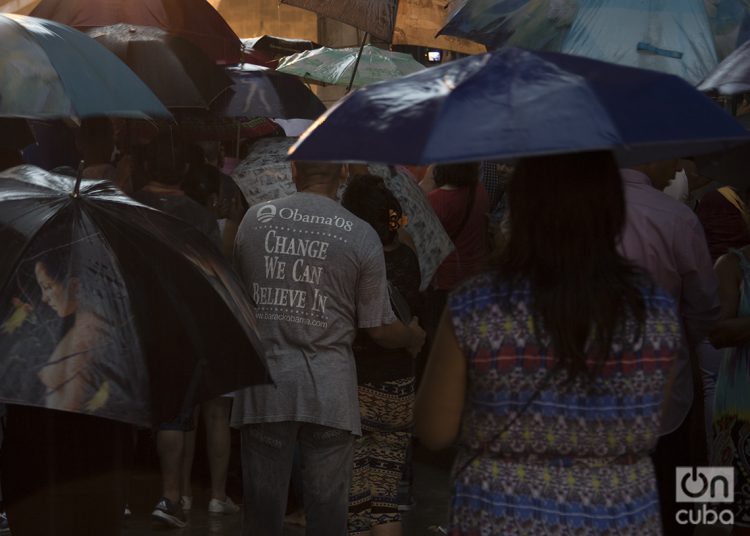

Despite Trump’s repeated falsehoods about Obama’s “one-sided deal” with Cuba, during its short duration, the policy of positive engagement achieved remarkable results. Obama’s opening allowed hundreds of thousands of U.S. citizens to exercise their constitutional right to travel to the island and see Cuba’s realities for themselves, among them Jill Biden, who spent four days there in October 2016 engaging “with a diverse range of Cubans on topics related to culture, education and health,” according to a White House press release.

The influx of U.S. travelers supported the rapid expansion of Cuba’s private sector, providing tens of thousands of Cubans with employment and incomes independent of the state sector. Obama’s authorization of tech companies such as Google to help Cuba modernize its internet connectivity directly contributed to giving the Cuban people greater access to information and opportunities for free expression in the digital public sphere. The full restoration of diplomatic relations, and the civil tone of diplomacy that accompanied it, produced 22 bilateral agreements on issues of mutual interest, creating a framework for ongoing collaboration on counter-narcotics, counter-terrorism, environmental preservation, disaster management and immigration.

During the campaign, Biden pledged to move quickly to change “the failed Trump policies that inflicted harm on Cubans and their families,” and to remove travel restrictions on Americans, whom he calls “the best ambassadors for freedom.” He and his top national security aides know from experience that a policy of positive engagement is not a concession to the Cuban government, but rather an effective advancement of U.S. interests in Cuba and the region.

“America chooses to cut loose the shackles of the past so as to reach for a better future — for the Cuban people, for the American people, for our entire hemisphere and for the world,” Obama announced on Dec. 17, 2014. Trump reimposed those shackles. If Biden has the determination to avoid the morass of quid pro quo incrementalism, his administration has the opportunity to cut those shackles loose once again.

Note:

*This text was originally published by The Sun Sentinel.