Photos: Courtesy of the artist

It may be said that certain focal points of everyday life — the ones that some refer to as prosaic — are a constant in the work of painter Rubén Alpízar (Santiago de Cuba, 1965), an artist who has successfully invigorated a particular esthetic, in which humor, almost bordering on irony, invites us to reflection.

Self-representation, too, is a way he has found to communicate with the viewer: his work is loaded with messages, suggestions and even light-hearted spaces that harmoniously blend together into a relationship of dialogue with the beholder.

In each of his designs, we can perceive a wink at the profession, thanks to his polished technique, achieved through academic training: four years’ basic and four years’ mid-level studies at the José Joaquin Tejada provincial school of visual arts in Santiago de Cuba; subsequently, from 1984 to 1989, he was enrolled at Havana’s ISA, the Instituto Superior de Arte.

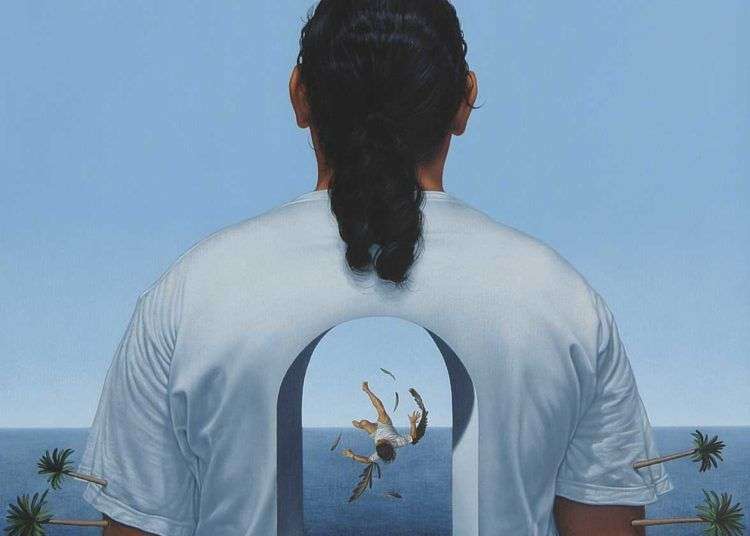

That formal training at different levels has allowed him to maintain, support and bear out an extremely personal pictorial discourse that, with the passage of time, has become drawn together in series. The most recent are: Callabos de Troya (Trojan Horses), El sabor de las lágrimas (The Taste of Tears) and Ícaro (Icarus). And as he delights in what is known as the “painter’s trade,” over and over again Alpízar takes on “life itself” as his greatest theme: “to run into a story, a joke, an anecdote, something that people read to you, a reality, every day: that is basic. Love, too, is essential, and of course, so are the problems that we have to face every day,” he commented to OnCuba.

His paintings seem to be supported by religious iconography — which he included from early on — but his work is not. Religion is just a pretext for addressing earthly, universal and human themes, while his arguments are transmitted through a fine prism with nuances of the absurd and even sarcasm.

The media he uses are totally interwoven with his designs, to the extent that the painting almost becomes a sculpture; a marked interest in breaking with planimetrics can be seen, including when he uses lavish textures. Perhaps that play with volume contains an incitation to observe the painting with something of a lucid, interactive approach: “it is not a question of touching the painting, but of making people inclined to touch it, to look at it from behind, from ahead or from one side,” he emphasizes.

Alpízar is a painter who uses almost all colors, but at the same time, his tones are filtered using the “velatura” technique, which give a sensation of aging: the most prominent colors on his palette are opaque greens, grays, siennas and pastel blues.

When experiencing his work, you are overcome by a feeling of looking at a stage production, because his work is full of theatricality: each painting narrates a story from beginning to end with climactic moments, all of it part of a painstaking process of creation: “I am very meticulous, very fussy. First I organize my ideas — I put together a type of story — and describe how each element how will be placed and what I want to say, and I even draw up the composition: this goes here, that element goes in that corner, and that one goes on the other side. I also make note of the reference: this character is taken from such-and-such a painting. That is how I shape the general idea of the piece.

Alpízar highlights the relationship between the person and time, because he knows that every human beings inhabits a certain period of time — the one that he strives to capture on every canvas. He is also a real architect of parody, which no doubt is useful to him for reflecting on specific themes of Cuba today with a perspective that is sharp and questioning, but above all transparent and authentically sincere.

-60-x-50-cm-Impresión-lightjet-sobre-KODAK-Endura-papel-fotográfico_0-120x86.jpg)

_0-75x75.jpg)