Spanish Radio and Television (RTVE) reported at the end of January that they had just rescued from the archives an episode of the legendary program A Fondo, directed and hosted by Spanish journalist Joaquín Soler Serrano. It is about the barely known conversation that he had with Cuban writer, painter and ethnologist Lydia Cabrera. To achieve this he had to travel from Madrid to Miami.

The program was aired on May 17, 1981. It had been recorded somewhere in Coral Gables. Soler Serrano himself said that they had had to go to “Florida, the Sunshine State” to be able to carry out what he had been planning for a long time; and underlines in his elegant and informed style: “Our long, tenacious search for years was not successful, and since she did not come to Spain, we came to look for her.”

The woman in front of him, sitting a short distance away, has a slow, confident manner. Throughout the talk, her expression will show a subtle sense of humor, a strong will and the knowledge that sustains the nobility of her blood. Between the two of them are the books that the interviewee has written during long and intense years of research.

Cuentos Negros de Cuba, El Monte, Anagó. Vocabulario Lucumí, La sociedad secreta Abakuá, La laguna sagrada de San Joaquín, Ayapá: cuentos de Jicotea, Refranes de negros Viejos…. Although she spoke of others that she kept unpublished and did not expect to print, because “printing is very expensive.”

Atentos a la chara 'A fondo' de Joaquín Soler Serrano con la escritora Lydia Cabrera. La recuperamos de mayo de 1981 –> https://t.co/BPlcxZvRvU pic.twitter.com/06jOtX4pqY

— Archivo RTVE (@ArchivoRTVE) January 30, 2024

Lydia Cabrera is 80 years old, but a burst of freshness prevails over her. “I am a very young octogenarian,” she warns sarcastically, aware that that conversation will not be enough to tell her story, that no matter how much she digs into her past, the interviewer will not have all the answers to explain a life also marked by legend.

She has silver hair and wears tortoiseshell glasses. She is wearing a dress with a leopard skin print and black shoes. Crossed legs. “I’m a very shy person,” she warns, smiling, slightly leaning on the couch, thoughtful. She adds: “I’ve always been a lonely person.”

At that time she had already been in exile for 20 years, nurturing what the journalist will call the “other Cuba,” the one that was beginning to move away from “Fidel’s Cuba,” or from “Castro’s Cuba”; and about which the interviewee makes few references, although she remembers the destruction of a project that she had been lovingly putting together with María Teresa de Rojas, Titina, in Marianao.

Both would have wanted to transform the Quinta de San José, the shared residence for years, into a Museum in which the “Cuban people” could see the evolution of “the Cuban house.” But, with her departure from the island after the Revolution, the property ended up demolished and nothing was known about the hundreds of objects it treasured. It was the year 1960. “I knew everything that was going to happen,” she says: “what worried me was the hysteria….”

What she does abound in is an idea that had fascinated her since her youth: the deeply rooted magical African world in that Cuba of stone and water that no human being will be able to alter or displace from the point where it emerged, interposing promisingly between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Unsuspected, almost virgin vestiges of an ancestry deeply established in the blood of the nation were visible before her eyes: the African.

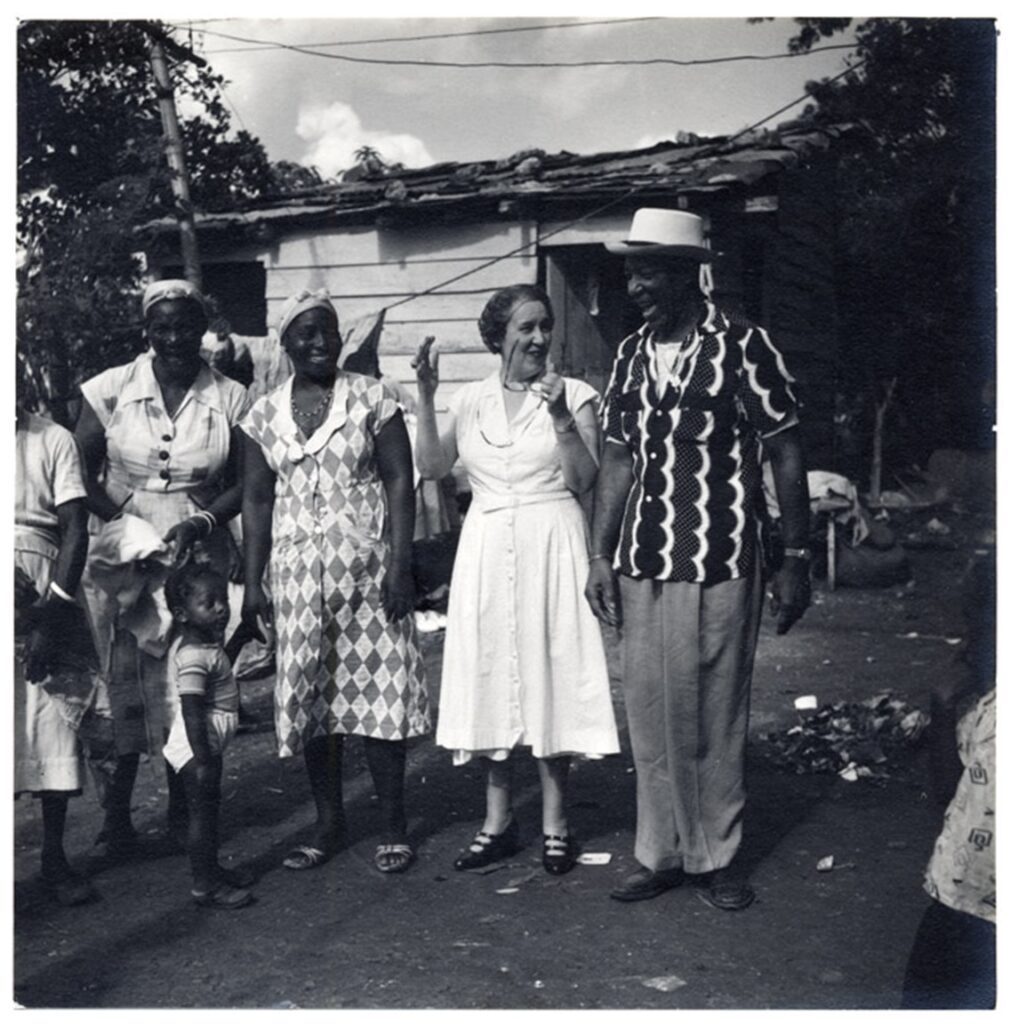

It was like a stubborn preservation of a memory, so strongly emphasized that, for example, “many things that were lost in Nigeria were preserved very pure in Cuba.” Seeking testimonies for works and books that she decided to write inspired by her studies of Eastern traditions, she interviewed hundreds of black people, survivors of plantations or servants in cities such as Trinidad, Havana and Matanzas.

In those places she discovered that even past languages such as Yoruba were preserved, and traditions remained intact, the preservation of which she attributed to the fact that the laws during slavery were “more humane” in Spain, and consequently, on the island, thanks to the “temperament of the Spanish.” There is a phrase referred to by a former slave to the researcher that says much more than what she expresses: “No, child, no way, in those times we were very well off.”

The connection with the magical world of black Africans had been so powerful on the island that Cabrera was convinced that that African heritage, “the gods,” had also moved into exile and that cities like Miami or New York had been filled with Lucumí and Nzo Ngangas temples, of conga magic. She claimed even more: that many compatriots returned to the place they had left solely for the idea of “getting initiated” into that fascinating world of spirituality.

As Serrano pointed out, based on a quote taken from the researcher’s books, for a type of people, life is something that must be protected by magical means and many people also need these powers to survive in a strange land.

The investigation of that cosmos determined the future of Lydia Cabrera, it consolidated her fame and gave her a special place in literature itself. Not by chance, when establishing a kind of exemplification of the canon of the insular voice, Guillermo Cabrera Infante places her since the late sixties alongside José Martí, José Lezama Lima, Virgilio Piñera, Lino Novás Calvo, Alejo Carpentier and Nicolás Guillén.

Lydia Cabrera was born on May 20, two years before history marked the date for the island. For this reason, she considered her birth “a joy of independence,” since she “was not programmed.” She was the youngest of eight siblings. Among them, Emma was her favorite and perhaps Esther, who was married until her death to Fernando Ortiz and unintentionally strengthened the relationship with the person who would be her initiator “in the taste for Afro-Cuban folklore.” 1

Her childhood was spent in a house on Galiano Street that is impossible to trace today (they tell me), in whose library, her father’s, she learned to read, an exercise forged in her constant visits to the printing presses of Cuba y America, the magazine founded in New York by her father, Raimundo Cabrera, who was a lawyer, writer, journalist, founder of the Autonomist Party and president of the Friends of the Country Economic Society. “Interesting guy my old man,” she says.

She accompanied her sister Emma to classes in San Alejandro and consolidated an artistic vocation with family friends, such as painter Leopoldo Romañach, who used to work in the Cabrera home itself. She then went to France, where she had a painting studio that she abandoned when she understood that she should dedicate herself to research and literature. She had understood that her country hid an unexplored world to which she wanted to bear witness. “I always say and repeat that you never see what is close to you.”

El Monte was what “dazzled” her, the encyclopedia where she showed us that “the saints” are not in heaven, but “on the mountain.” But, in addition, she wrote dozens of stories and fables linked to the mystical and animal world. “Animal folklore in Cuba is very rich,” she tells her interviewer, who has drawn attention to stories in which she notices an abundance of animal stories, and briefly establishes an analogy with Rudyard Kipling, the famous English author whom the author met at a Czech spa in 1937.

For Fernando Ortiz, texts like Cuentos Negros en Cuba open “a new folklore chapter in Cuban literature.” The assertion was made in the prologue of the Cuban edition, in 1940, where he explains that “these stories-fables imagined in an African language (Yoruba, Ewe or Bantu), have been translated into a mixed and dialectal language of Cuban blacks” on which Cabrera worked, in what he calls “a second translation.”

It is, Ortiz points out, a “difficult, but loyal” task, which gave rise to “a new addition to folklore literature in Cuba” thanks to the “spontaneity of her poetry and her art” and the fact that they were narratives “full of fantasy” that arrived on the island preceded by great success thanks to its edition, in French, in 1936, thanks to Gallimard.

Already in the magazine Estudios afrocubanos, the voice of the Society of Afro-Cuban Studies whose president was Ortiz himself, one of those stories by Lydia Cabrera (“Susundamba,” dedicated to Alejo Carpentier) had been published in 1938, although this is not included in the book. Those stories were written by chance, she said, “to amuse Teresa de la Parra, the Venezuelan who was a very good friend of mine.”

“Los Cuentos Negros by Lydia Cabrera constitute a unique work in our literature. They provide a new accent. They are of dazzling originality. They place Antillean mythology in the category of universal values. And if they make me evoke the names of Kipling, Lord Dunsany and Selma Lagerlöf, it is because, with remote and involuntary analogies of purpose, they withstand comparison with certain stories by these authors,” Carpentier assured, shortly after the French edition came out.

Lydia Cabrera died in Miami ten years after the interview with Soler Serrano. In testimony collected by researcher Madeline Cámara, her friend and executor Isabel Castellanos says that she gradually faded away after weeks suffering from serious macular degeneration of the retina that had deteriorated her activity, her work “and the great entertainment that painting, writing, reading were for her.” 2

On the night of her death, in the midst of her serenity, Lydia Cabrera murmured a timid word: “Havana!” Her friend wanted to know what she had said, and she repeated the name of the city that had seen her born at the beginning of the 20th century. “That you are in Havana?” Castellanos says she asked, to which the writer responded with a nostalgic and definitive statement.

“Where did you get all that history?” Lydia Cabrera asked during the interview. “Well, from the archives,” she responded along with Soler Serrano.

________________________________________

Sources:

“Susundamba,” Lydia Cabrera: in Estudios Afrocubanos, N.1 Vol. II, 1938, p. 58.

Cuentos Negros de Cuba, Lydia Cabrera, Havana, La Verónica, 1940, digital edition.

“La muerte de Trotsky referida por varios escritores cubanos, años después- o antes,” in: Tres Tristes Tigres, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Biblioteca Ayacucho, 1990.

Alejo Carpentier, “Cuentos Negros de Lydia Cabrera,” in: Carteles, Havana, 28 (41), p. 40, October 11, 1936.

Notes:

1 Fernando Ortiz, in “Prejuicio” a Cuentos Negros de Cuba. Havana, 1940.

2 Testimony read in: “Diosas de ébano para Cuentos negros de Cuba de Lydia Cabrera,” doctoral thesis by María Goretti Sánchez, digital edition.