I say that there is no political education like traveling, to get to know directly how people in other places live and think about their own problems. When I visited India a few years ago, on an exchange with academic and government institutions, I learned that, for them, the first constitution as an independent nation, stamped with Nehru’s imprint, was definitely socialist.

When I asked them about the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi, one commented to me: “It is repeated that he was a pacifist. But the truth is that he was a great strategist, who invented a way to wage war on the British empire. And win.”

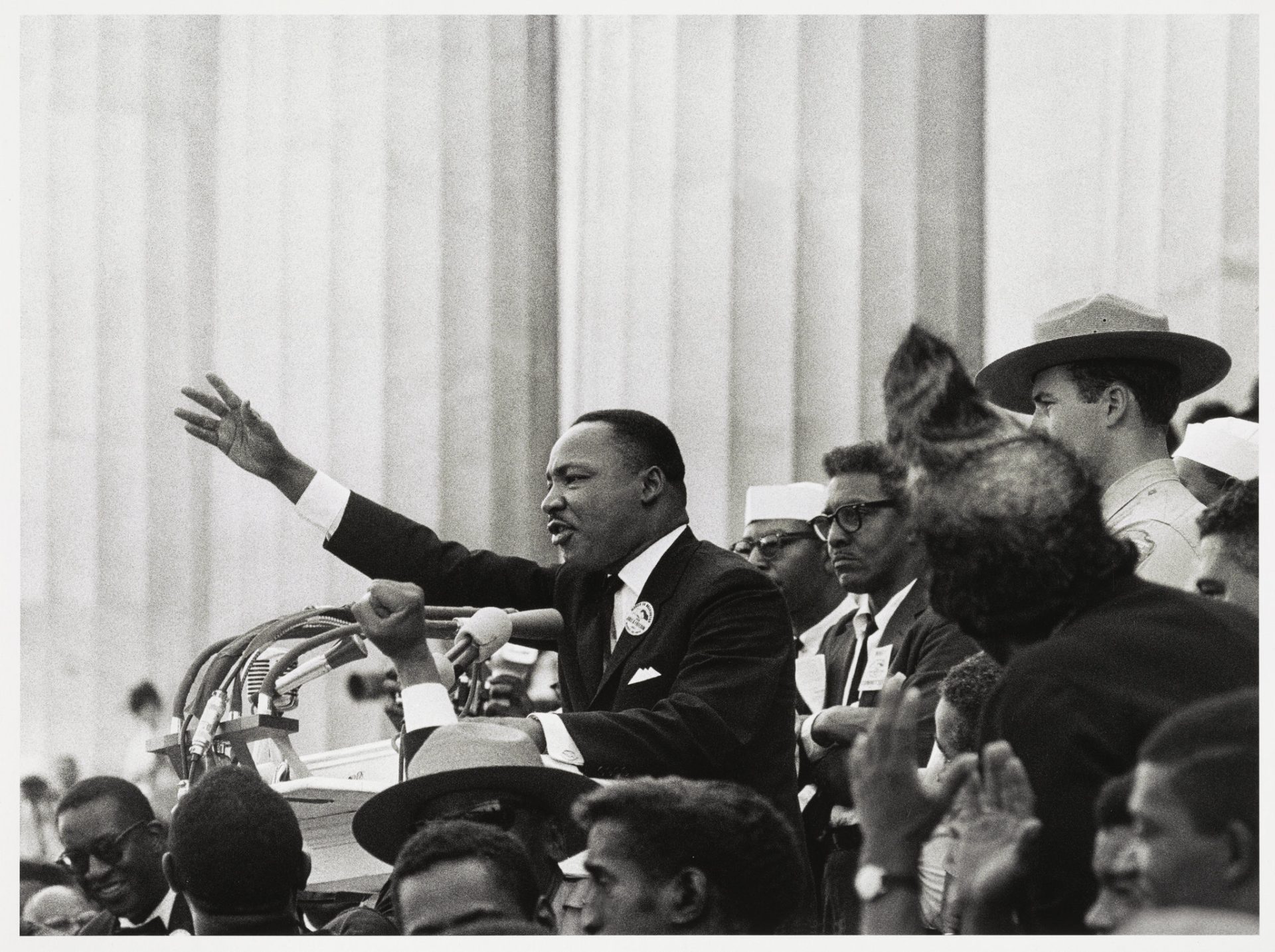

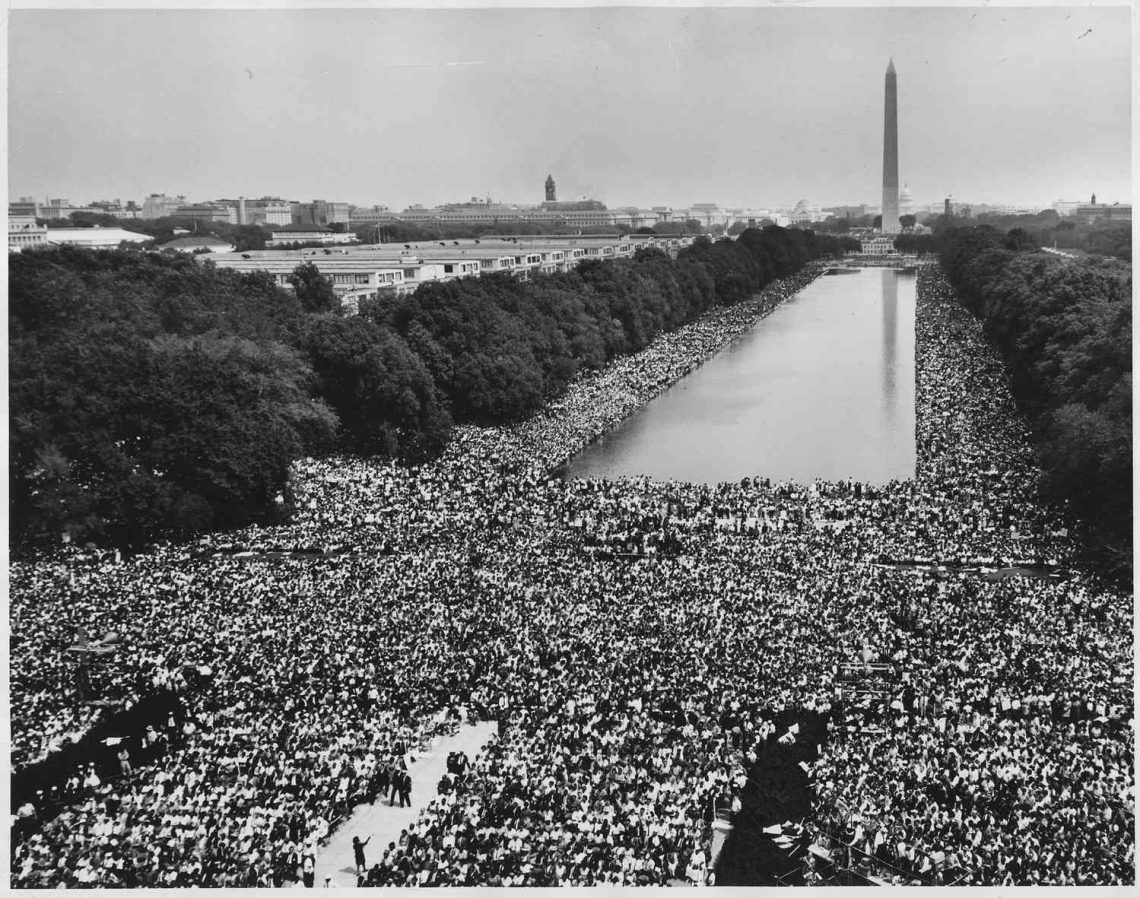

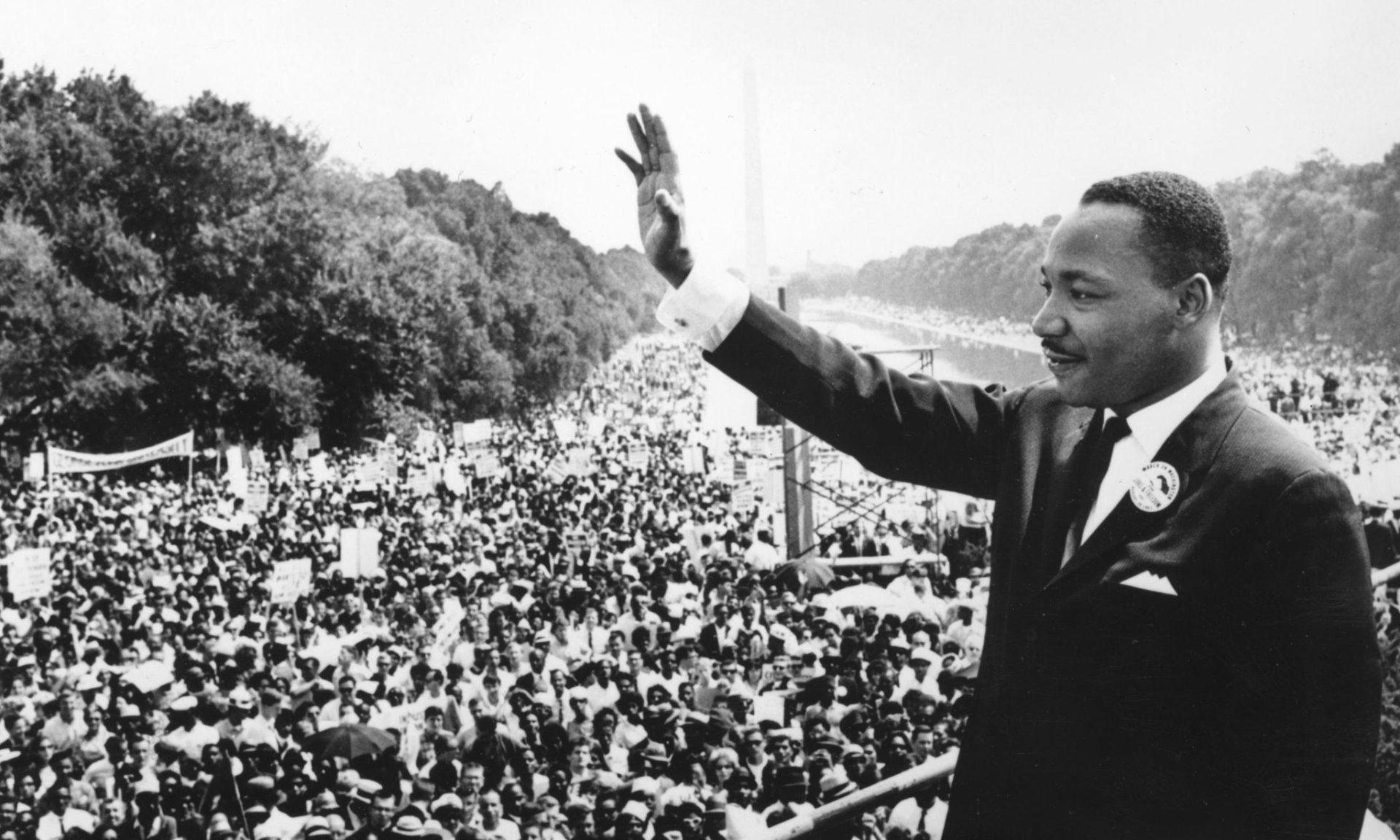

Rereading today the extraordinary political speech that, in the form of the Sermon on the Mount, Martin Luther King gave 60 years ago, at the end of the gigantic march for civil rights and in front of the Lincoln mausoleum, that singular characterization of Gandhi heard in India comes to my mind.

With the drama of evangelical prophecies, the Baptist pastor, turned into a civic and political leader, constantly addresses the established powers, warning them about the seriousness of the moment. A few steps from the monumental Roman Empire style buildings, designed by Pierre L’Enfant, to produce the same effect as the Caesars on subjects and barbarian nations, MLK alludes to these powers with names and surnames, and demands the payment of a promise pending for exactly one hundred years. The emancipation of the slaves has not been fulfilled, and that march of thousands is there to remember it.

He urges the marchers not to be swept away by the brutality with which many of them have been repressed; to the discriminated against in the deep South, who still cannot go to the same schools, the same hotels, parks, bathrooms and drinking fountains, seats in public transport, jobs as the “whites.” But he does not ask for patience from those discriminated against and repressed. His call is not to fire back at the police, nor take to the streets to assault or burn government offices, so as not to give the established powers the justification to escalate the repression.

King’s speech establishes an inescapable link between freedom and justice, as if one were not conceivable without the other. Here justice means equality, for he asserts that “the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality.” And he challenges from the outset any attempt to postpone solutions, through what he calls “the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.” In other words, there is no more time: “It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.” Because if the Americans are not aware of the accumulated pressure, and it occurs to them that negroes have a psychological problem of “blowing off steam” and that they are going to be content with crumbs, as they believe it has been so far, “will have a rude awakening.”

That apocalyptic accent, in the biblical sense, alludes to something that will inevitably happen, not due to a lack of good will or desire, but due to the force of social factors that cannot be manipulated by any political sleight of hand. So it does not contain a pacifying message, in the sense of appeasement, but a trumpet call like those that often appear in Old Testament biblical prophecies, and that are not at all peaceful.

I should have started by saying that this pastor of a church from the Deep South, rather conservative in his religious and moral values, has become a spokesman for a movement that transcends racial differences, has become a leader for many Americans who are not “negroes” “or “wretched of the earth,” but “whites” and middle-class people.

Because he is not an anarchist, a communist, a socialist, a genuine union representative of the workers, nor of any other current of the so-called radicals. Precisely for this reason, his call can be more alarming and dangerous than that of anti-war activists, counterculture activists, feminists, Black Panthers, and other opposition movements.

What is threatening for the establishment is, ultimately, that this call projects a vast alliance, closer to the concept of the people, than to a social class, a particular religious or ideological creed. And that it is not just because it does so within the law, but because it has become legitimate, which is something else, politically speaking. To the point that it does not constitute a separate discourse, separate from the nation and its symbols; a new utopia, a dream that is claimed as different, but rather embedded within the founding discourse of the United States.

Not for nothing when he says “I have a dream,” he is quick to add that it is “deeply rooted in the American dream.” And that it will make it possible for this nation to “rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed… truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” These are words from the U.S. Constitution.

These comments of mine are only an introduction to two texts that I attach. The first is a selection of excerpts from MLK’s speech on August 28, 1963, which I have made expressly for this anniversary. The second consists of my interview with two people linked to the subject, and subjected to similar interrogation: one, an American, lawyer and professor of civil rights in Alabama; the other, Cuban, Baptist leader, and social and political thinker.

I leave readers in that good company.

MLK’s speech on August 28, 1963

(Excerpts)

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice…

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free… the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity… the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land…

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men…would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness…. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt… And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism… Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice…

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges…

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice… We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny…

We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed…

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today…

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day…

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true… And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

The struggle for civil rights and MLK’s imprint

Visions from the United States and Cuba

I don’t know anyone who has such a deep, singular and intimate intellectual mastery and life experience on this topic as my two interviewees. I thank both of them for sharing their special testimony, inseparable from a personal commitment, but also a sign of our inveterate friendship.

Stanley Murphy is a civil rights attorney in Alabama, where he has taught at the state’s premier university. He descends from a family of white lawyers and judges, who got involved in the struggle against racism in its most recalcitrant expression, challenging the political class and the Ku Klux Klan, in circumstances of the greatest confrontation and violence.

Joel Suárez is the director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Center (CMMLK) in Havana, who also descends from religious figures committed to their faith and to social change, and who combines the qualities of a leader and a social, theological thinker and politician recognized in Cuba, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Stan, how do you rate the achievements of the civil rights movements in the 1960s?

Stanley Murphy (SM): As of the 1940s and for the next two decades, the United States began to use the power of federal law against the largely atrophied principles of racial equity that were first formalized after the Civil War (1861-1865). Except for slavery proper, virtually none of the institutionalized forms of racial inequality changed. Indeed, in practice, the combination of unbridled police power with economic and political forces acting in complicity or with deliberate indifference meant that slavery-like forms of forced labor existed even well into the 20th century.

Using both explicit legal prohibitions and entrenched norms, they were excluded from educational programs, public services, and opportunities for political expression and participation in public administration. Although the legacy of racial inequality was not limited to southern states, it was in the South where it was formalized as state law. It was only thanks to decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, statutes passed by Congress, and increasingly by the action of the Presidents, that legalized barriers to racial equality could begin to be removed.

That work to dismantle the legal and cultural structures of racial discrimination required lawyers and judges who were willing to risk their careers and personal safety to enforce America’s laws. Most of them remained on the sidelines or showed no interest. The few who did take the plunge are responsible for many of the achievements of the 1950s and 1960s, to invalidate the explicitly racist post-Civil War holdovers in the South.

Among the most significant developments was the growing awareness that the very laws and mechanisms that underpinned the mistreatment of Black citizens also prevented other vulnerable people from having full access to many of the same opportunities long denied for racial motives.

A great step forward in the legislation was the recognition of the abuse of power, be it governmental, economic, or as in the case of the KKK, private criminality, against which the government did not protect citizens, whose common motive was also applied against other vulnerable groups and could be countered by the same legal principles developed in the struggle for racial equity. Thus, to think of the civil rights movement as tied only to race was to limit it too much.

Joel, what did MLK represent for the civil rights struggles in the United States in the 1960s? What value did the speech at the Lincoln Memorial have in that context?

Joel Suárez (JS): As often happens with some songs like “Imagine,” by John Lennon, or “Blowing in the Wind,” by Bob Dylan, their musical and poetic beauty, their contents or utopian references hide or make invisible a radical work. With “I have a dream,” the biblical references, the ethnology of gospel, black spiritual, as well as the Constitution and other historical documents of the United States, that poetic part present in the best of the tradition of Davidic songs and from the psalms of the Bible, from the Old Testament prophetic tradition, hide a whole area of the speech where he gives a tremendous blow in the middle of that historic, imposing and important march, to American society and its founding values.

In that speech, as early as 1963, one can appreciate MLK’s theopolitical itinerary, which will have its peak on April 4, 1967, the year before his assassination, at Riverside Church, when he said he was against many of the religious leaders of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and the Southern Conference of Religious Leaders, which had a great weight in the leadership of the civil rights movement, who did not want their struggles for civil rights tainted with the antiwar movement.

There were very radical areas, like the Black Panthers, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Weathermen, the groups linked to the entire cultural mobilization, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Robbins, Allen Ginsberg, etc., a very radical area, just like those of clergy, religious leaders and other confessions, and who were also organized, and it is precisely them, like William Sloane Coffin, who many years later was pastor of Riverside Church. When I met him, they urged him to take the step, and his famous sermon Beyond Vietnam, a very radical and very anti-systemic speech, is a criticism not only of the war but also of poverty and inequality, which implied his death warrant.

And how was MLK’s legacy received in Cuba at that time? Why did the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Pogolotti choose the name MLK to found the Center in 1987?

JS: Although Cuba’s isolation in the 1960s did not allow access to all of MLK’s theopolitical production, his sermons, books, etc., after he was awarded the Nobel Prize and died, there is a group of churches from here in the city that started meeting to honor him and gather around his memory.

Among his texts I especially remember Quo vadis, Chaos and community, Why can’t we wait? and the famous Letter from Birmingham Prison (April 16, 1963), which reached us in letter envelopes, because those who sent them took a bundle of sheets from the books, put them in letters, and when they arrived, we recomposed them in books here.

Already in the late 1970s, through Mexico and its theological community, contact was maintained with all the work of Latin American liberation theology. The encounter between this and the black theology of liberation was crucial, despite their areas of conflict, due to the perspectives and analyses that were based in each case, the racial and socio-class perspectives.

In those years and in that theopolitical itinerary, in the particular case of the pastors of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Marianao, a complex process took place, which implied dismantling all the heavy armor of Saul, that is, the ideocultural scheme formatted by the Baptists from the United States through the Baptist Theological Seminary, to understand the revolutionary situation that the country was experiencing and take the subsequent steps, known to all.

In this sense, the figure of MLK had an extraordinary pedagogical value. First, because he was a pastor, and that gave him authority. Second, a pastor from the southern United States, that is, from the same area to which the tradition of our Western Cuban Baptists belonged. In other words, anchored in his faith and in his biblical-theological reflection, he opts for social justice.

This was a factor in the awareness processes towards the faith community, the members of the church who were involved in that process, and towards other Baptists, as it was a referent that broke with the traditions of the missionaries and Baptist leaders of the south, which MLK criticizes in a very prescient way in his Letter from Birmingham Prison.

Through the theological community in Mexico, Reverend Raúl Suárez studies Latin American liberation theology and attends those meetings of theologians and social scientists between that theology and black theology. There we made contact with Dr. Howard Dodson and his wife Jualynne, who at that time led and conducted the Black Theology Project.

This access to the philosophy of MLK, to the knowledge of his life, of his work, favors that, when the church decides to constitute a center at the service of sociotheological, pastoral, popular formation, social and community work, it decides to name it Martin Luther King.

In addition, the name came to challenge a reality that hit us directly: that of a Cuban church of southern tradition, Anglo-Saxon in its worldview, in its liturgy. Although ours was a neighborhood church, culturally it was a white church, but located in a neighborhood that you know, the first working-class neighborhood of Havana, the Pogolotti neighborhood, with strong cultural and religious traditions, a power in terms of religious traditions and cultural origins of Africa.

The insertion of the church in the community, and the life of the church in that community, could not ignore that fact. Over the years, as a result of all this process, it is a multiracial church with a liturgy more attached to traditions that make up Cuban culture today.

Stan, how far have those movements come since then?

SM: Without minimizing the immense value of the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. The Board of Education, or the passage by Congress of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, when we say that, by themselves, they hardly ever have any real practical influence on the quality of daily life for people who they were meant to protect. Every legal protection that the courts or Congress expected to derive from their decisions and statutes has given rise to thousands of disputes, lawsuits, and political struggles in the ensuing decades. The process of applying the legal principles of equitable treatment has been slow and sometimes bitter. And the thing continues. But, in my opinion, great strides have been made and, as difficult as things may be even decades after the events of the 1950s and 1960s, the prospects are better and the results more lasting than in previous years.

Stan, how would you describe the current state of civil rights in the United States?

SM: Although things are vastly better than when I was growing up, today there is much less consensus as to whether less overt discriminatory practices or remnants of past discrimination continue to exist, or whether corrective measures for past behaviors or exclusions for reasons of race are appropriate.

Widespread ignorance of American history, including contemporary history, and the momentous events of the civil rights movement, can be a fundamental problem. There seems to be even less intention to learn anything from or about history, or even to allow students in schools to learn much about it. I’m afraid that without that basic knowledge, the progression of the “arc of justice” will be slower.

And then on which institutions does the implementation of civil rights legislation depend today?

SM: From my point of view as a lawyer, the courts have had and continue to have an essential function. Congress is basically immobilized on the issue, and the Supreme Court is systematically limiting the power of the President to take executive measures directed at the observance of fundamental rights.

With its investigations and reports, the news media remain as indispensable as ever, but deep economic tensions are reducing the effectiveness of journalism, the value of which is also undermined by the reflexive impulse of many to isolate themselves entirely from any journalism that represents a challenge to their particular vision of the world, which is very often far from objective reality.

They are followed by schools, although they are increasingly constrained by their own timidity and by overt political efforts to exclude “uncomfortable” topics such as race and racism from the classroom. Because many aspects of America’s racial history are uncomfortable, to say the least, not much will be taught or learned about historical perspective.

And looking at the present and the future, how do you see the main problems in the fight for civil rights right now?

SM: I think one of the main difficulties has been the ingenuity of the courts in interpreting the practical reality of life in the workplace, voting booths, schools, or even in jury boxes. Too often, court decisions in cases involving racial or gender discrimination claims reveal their ignorance of the pragmatic realities that gave rise to the dispute, as well as a troubling reluctance to learn.

In the last twenty years or so, the courts have created a whole series of procedural hurdles that interfere with many civil rights claims and often prevent claims for substantive violations from ever reaching the courts of law.

Courts dismiss many serious claims before lawyers and their clients can present sufficient evidence so that established legal principles can be rationally applied and appropriate compensation can be awarded.

These obstacles can become fatal barriers to justice for many injured persons, often deterring attorneys and victims from even filing a lawsuit. I fear that all progress will be slow until the courts are fully open to trials of civil rights claims.

Joel, what aspects of MLK’s legacy does the Martin Luther King Memorial Center consider most relevant today? How do they contribute to understanding the problems of both societies and to facilitate their dialogue and coexistence?

JS: Martin Luther King’s radical anti-racism is one of his fundamental legacies; which he links to poverty and the economic situation, from that speech of 1963, and throughout his work.

Just as his prophecy reminds you that we do not have the right to wait, and that in the face of the challenges of the reality that the world is experiencing, including Cuba, we must take positions like those of the great prophets of the Old Testament.

In this legacy, criticism of religion, of the immobility of the churches, continues to be a key component; of a certain passivity, although it is no longer the mark on the religious scene, taking into account the new movements and the so-called evangelical religious fundamentalisms.

In this legacy also includes discovering how his thinking evolves, especially based on permanent dialogue and openness in the face of the challenges of reality.

In the midst of this radical prophetic speech, there is also the tradition of biblical teachings referring to compassion, mercy, love, with an extraordinary radicalness, which is not exhausted in some of those beautiful phrases that swarm on social media and sometimes reduce the projection of those great figures.

When I mentioned MLK’s prophecy linked to the tradition of Old Testament prophecy, I was referring to that classic attitude of the prophet, who is the man on the road, not the man on the balcony; involved in conflicts, and who opts in the conflict for the side of justice and the dignity of the human being. And who celebrates or denounces in human projects, depending on the facts that they produce, according to the path towards the greatest amount of happiness possible for each and everyone, and to which today we would also add the care of nature. When realities lacerate the dignity of human beings, the prophet, like MLK, denounces them, even if it is at the cost of his life.

He always reminds me of that phrase from the Apocalypse: “If you are not hot or cold, I will expel you from my mouth.” An expression of the prophetism of Saint John in the Apocalypse, that is, the man who takes sides for a cause, exercising that difficult and complex role of announcing and denouncing.

For the Cuban reality today, that appeal of “why can’t we wait?” is like a coal burning on our lips.