In a treatise of his with the disturbing title of Política de Dios, Francisco de Quevedo affirms: “All the princes, kings and monarchs of the world have suffered servitude and slavery: only Jesus Christ was king in all freedom.” Did he know what the great writer, and man of his time, was talking about? Is it that the freedom of the spirit, that of the people, politics, can be touched with the hands? And what does faith have to do with all that? These notes try to land these questions and others.

Note 1

Almost a decade ago, Father Espeja invited me to speak in the Aula Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, in the San Juan de Letrán Church of the Dominican friars, located in the heart of El Vedado. His invitation contained a bait question: What do you believe?

“I believe,” I told him, “in the power of creative thought.”

Of all my talking that night, which I cautiously spared the reader, I remember having invoked the Dominican motto, “veritas, amor veritatis”, which amounts to something like “truth conceived from the love of truth.” My argument was that the truth is not just about contemplating it, but about exercising and communicating it; that is, of interacting with others. “It also has to be defended from its enemies”, I finally added, “because it has enemies.”

My friend Jesús Espeja, then parish priest of the El Fanguito neighborhood, on the banks of the Almendares River, never asked for the sake of asking. So he asked me the second: And what does that have to do with your life?

I will remember a couple of tenuous ideas, rather brushstrokes, with which I defended myself from that soft thrust of his.

We tend to think of the Revolution as a radical break in the life of the nation, in the existence and experience of all of us, in the flow of events — and there is no doubt that it meant all of that. However, it also resulted in a process that is inseparably linked to our previous life, and that becomes inextricable from that past that we carried — and continue to carry — inside. In my case, that life had to do with the different faiths (like that, in the plural) acquired until then.

The Revolution renewed among Cubans — not only religious believers — the idea of a kind of promised land contained in the postponed patriotic utopia. Boys and young people like me tended to live it not as a doctrine, a philosophy, an ideology, but as a vital vibration, a belief.

The revolutionary ideology as a link with a previous faith was in my eyes very compatible with everything I had read and learned in the sayings of the Gospel. “Blessed are the poor, for theirs will be the kingdom of heaven”; “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven,” “Leave everything you have and follow me,” were consistent with “The homeland is an altar, not a pedestal,” “I wish to cast my luck with the poor of the earth,” and with the calls to make homeland and defend it. Because it was clear that the Homeland was not “a piece of cloth,” as Emiliano Zapata is said to have said; that is to say, it was not an invocation, a symbol, a constitutional concept, a great tree that shelters us all like birds in the rain, etc.; but something very visible and touchable, especially when it has to be defended with actions.

Faith in the Revolution also brought with it adventure and freedom. Leaving the games behind and going to teach people how to read and write was not only fulfilling an idea of social justice, but rather running away from home “with permission.” It was a very palpable adventure to go away to teach reading and writing for more than half a year at the top of a hill, far from the family’s control, and also an infallible temptation. Of course, for those of us who got hooked on the Revolution with the literacy campaign, it was an ethical demand: a man had to do something like teach those who don’t know and the poor.

To a large extent, the Revolution was that, an intoxicating sensation of freedom. Naturally, we learned much more from the farmers in the countryside than we taught them. As Saint Paul said to the Romans: “You then, who teaches another, don’t you teach yourself?”

To a large extent, the ideology of the Revolution came to be a new secular faith, which worked on values acquired in previous religious education. Going to teach with a rosary around the neck and a Marxist pamphlet in hand was as coherent as dozens of friends were doing it. Perched on those hills we were happy, we participated at the same time in an adventure and in the transmutation of our faith. When we came down, we were others.

Then something unforeseen happened: the forced choice between religious faith and that of the Revolution. The obligation to choose between one or the other posed a dilemma for religious believers in Cuba. Although, if you think of adolescents or young people like those, choosing between life in the Church and the revolutionary adventure was a decision that didn’t take long to make. Especially since the acquisition of the new faith incorporated and subsumed values acquired in civic education and in the commitment professed in the basic faith.

The last point of my confession to Father Espeja was that of heterodoxy. In the history of the Church, heterodoxy almost always leads to heresy, assumed as a breach or refutation, in a negative sense. My position was to emphasize the positive side of heterodoxy and heresy, as they are sources of renewal of the doctrine and its advance.

If we look back at any religious current, we appreciate that, after the heretics and the heterodox, comes a renewal that enriched the doctrine and made it advance. Then, even though they have been burned at the stake, those heretics made crucial contributions. Without heretics we would not have updated the tradition, nor would we be able to use it in a creative way. So it is that heterodoxy, both in religion and in any other manifestation of culture and thought, is decisive for creative thought.

When heresy raises the criticism of dogma, the thing is not reduced to someone else’s dogma, but ours, to the one in which we grew up and of which we are unaware, unless we put our creative eye on ourselves. “Why do you look at the speck that is in your brother’s eye and do not see the beam that is in your eye?” says the evangelist Matthew. We have to look at the dogmas that survive in us, and that do not constitute transcendental ideas or values, but only dogmas, sterile by definition.

But in the end, if some truths became dogmas, it is not for that reason that they must be repudiated; but rather, let’s say, recreate them. Jesus says: “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” The same as Gramsci: “The truth is always revolutionary.”

A faith or a church without heretics is like a system without antibodies. I don’t know if Cuban religious people can agree, or perhaps it seems to them that spiritual health lies in thinking alike, and celebrating it. In any case, if heresy is not simple antagonism with what others believe, but something deeper and more transformative about one’s own faith, today it seems conspicuous by its absence in the Cuban landscape. At least among believers.

Note 2

In his second letter to the Corinthians, Saint Paul affirms “that God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself, not counting men’s sins against them, and entrusted to us the word of reconciliation.”

“Us” in this quote referred to the Christians, whose mission 2,000 years ago was to transmit the Word. This would have the power to illuminate the hearts and minds of people of goodwill and even of those who did not have a very good will, and who would also be touched by his Grace. The message was so strong that it did not require repeated ideas, material stimuli, threats to burn in hell forever, or compulsion of any kind. The Kingdom of God was open to all who lived in love for their neighbor, even if they were sinners, or even dogmatic and sectarian Pharisees.

The Christian evangelizers of that time did not operate from apparatuses structured from top to bottom, networks extended between nations and borders, hierarchies that made decisions without giving account to their followers, or authority other than that which emanated from their mission. No one was above the other believers or had a seniority in the interpretation of the ideas of Jesus the Messiah. The word “church” barely meant a gathering of citizens or of the faithful.

As is fame, Saint Paul did not always preach love of Christ and reconciliation. Before he had been a Pharisee jealous of everything that was not his faith, dedicated to persecuting, imprisoning, and rushing to death those who proclaimed the arrival of the Messiah, a subject of the dominant Roman empire in almost the entire known world. Hunting Christians, with his first name, Saul of Tarsus, he was on the road to Damascus, when the Lord Jesus Christ appeared to him in the form of lightning, and right there his conversion to the chosen group of the apostles began, the only one among them who had previously been their inquisitor.

So, of all, Saul or Paul seemed the least equipped to preach reconciliation, and to represent the new man of Christianity. Naturally, this preaching could not be impregnated with the same viciousness with which he had persecuted the Christians. According to him, this new faith “tore down the intermediate wall of separation between the peoples, abolishing enmity in their flesh, the law of commandments expressed in ordinances, to create in themselves from the two a new man, thus establishing peace, and to reconcile the two in one body.”

That new man was a preferred addressee of his epistles, the most powerful doctrinal group in the New Testament: “No one despises your youth, but be an example to the believers in word, conduct, love, spirit, faith and purity.” In short, not because you are young do you lack the ability to think and achieve great things; and above all, the magnitude of these conquests is measured by achieving the respect of others. It is not a precisely canonical or dogmatic message, but very earthly and full of human affection.

I wonder how much of the letter and the spirit of that Paul — who knew what he was talking about, because he had suffered it himself — is incorporated into the current religious calls, dedicated to a “true national reconciliation, which [supposedly] is achieved in the conflict.”

Let’s just say, to what extent the discourse of certain clergy and laity in today’s Cuba execrates the very idea of the new man in the name of a “loving Cubanness” lost in the fog of yesterday. Or he it dedicated to delving into “wounds and unresolved conflicts,” which must be healed with unique remedies. Or it declares “to lack hatred in the heart,” but with the same belligerent tone with which it disqualifies the cause of all evils: “a philosophy that ignores the truth about what gives full meaning to the human being,” a [socialist] system that has given rise to “the mutilation of critical thinking.” To end by scolding “this people, which many years ago turned its back on God, and when a people turns its back on God, it cannot walk.”

Combining all this with the words of Pope Francis in favor of “transparent, sincere and patient dialogue and negotiation” requires more than effort. The same as to connect it with the style and teachings of Saint Paul and the evangelists. Not in vain, Monsignor Carlos Manuel de Céspedes said that “the hierarchy [the bishops] has not historically distinguished itself by its talent to direct — “shepherd” — the political dimension of the life of the Church, located within the framework of its essential evangelizing mission.”

How and to what extent does this political vocation of the churches impregnate the faith of ordinary believers? Is it that everyone follows the voice that comes from above? And how does it color politics, in its most circumstantial sense, and intersects with other factors interested in bringing the embers to their sardine, as Saint Paul would say? For example, the speech on “the lack of religious freedom in Cuba.”

When some affirm that “the Cuban authorities increase the restrictions on religious freedom through new legislation and violence against those who express religious beliefs that the Cuban government perceives as opposed to its authority,” what legislative changes are they referring to? Is it, let’s say, that the Family Code “encourages systematic tolerance of current and scandalous violations of religious freedom”? To put it in a certain vernacular language, does this law deepen “the wound in the soul of Cuba which is the crisis of families”?

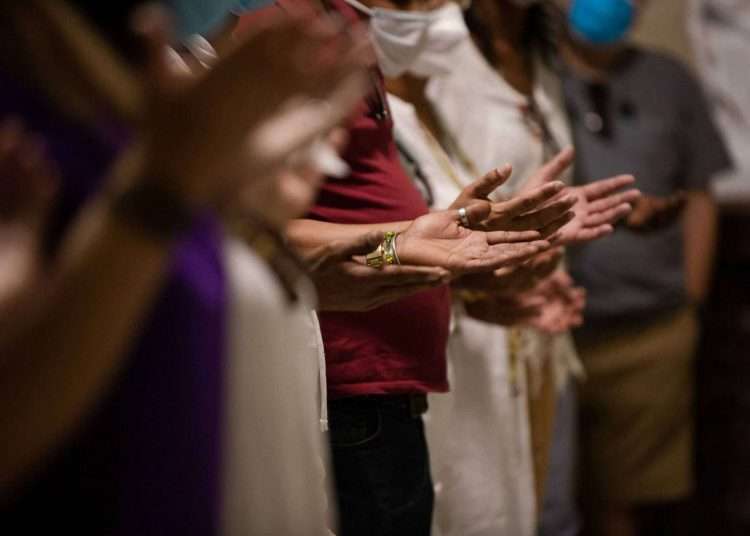

If it is about freedoms, it would be necessary to approach the society that lives and believes beyond that discourse.

To be continued…