Manuel R. Moreno Fraginals is a fascinating historian, and it would be very difficult to be so without also having a substantial life. Moreno always believed in collaboration to carry out his work. When I asked myself what type of text could be contributed as a novelty to what has been appearing this year, in which the centenary of the intellectual’s birth is celebrated, I conceived a collaboration that, written by various hands, would account for my fascination for his work and the interest in his life.

What follows is the result of that purpose. First, an interview with his daughter, Beatriz Moreno Masó, which explains the interest that his personal life arouses. (It should not be repeated here that the personal is political.) Then, a comment by renowned historian Joan Casanovas, professor of American history at the Rovira i Virgili University, in Tarragona, Catalonia (Spain), which delves into the reasons for the fascination that his work exercises. In the midst of work, we had several conversations among ourselves, with other colleagues, and with Moreno’s family.

Serve as an invitation to read the historian, an always lush shadow to understand Cuba, also in the 21st century.

(Julio César Guanche)

A very unique humanist

Interview with Beatriz Moreno Masó

The family

My father mentioned that one of his ancestors had been a smuggler in the central area of the country, near Trinidad. I don’t pay much attention to such stories. It was probably true, but many were, as they are, or are in some way, now. Having a smuggler in the family seemed to give Dad a certain romantic halo.

On the other hand, I do have evidence, in papers that I keep, of several Mambí fighters among our ancestors. Manuel Lico Moreno, my father’s grandfather, was a Mambí. He lived and fought in the area of Sancti Spíritus. After falling ill, he ended up committing suicide. Perhaps it was one of those old men who, seeing themselves useless, put an end to their life.

Since then, suicide has been a taboo subject in my family. My father always told us to shut up when the subject came up.

My mother, Beatriz Masó, also had a Mambí father, Carlos Massó—he was a relative of Bartolomé, with the same surname. Massó was a Catalan surname, from Sitges, but it seems he later preferred to write it as Masó, with a single s. Carlos fought with Calixto García. They called him captain “Candela,” because of his fierceness and speed to carry out orders. [Carlos Masó Hecheverría would become, according to Carlos Roloff, lieutenant colonel at the Headquarters of the Eastern Department.]

When my grandfather learned of the discharge from the Mambí Army, he said he would not accept any pension because he could work, which he did until he died. And he died, as happened to people at that time, of just anything, I don’t know from what.

My uncle Calixto Masó wrote a short biography of my grandfather Carlos. Calixto was a jurist, historian, and teacher. He was among those who staged the Protest of the 13 [1923]. Among other things, he taught in Evanston (Chicago). They are the turns of life: my grandson lives there today.

Calixto wrote “El carácter cubano” [published in 1941, but with texts dated from 1922] where he says that “witchcraft and ñañiguismo are also survivals in Cuba of the immoral and fetishistic customs of African blacks,” that the colonial regime was the main cause of “Cuban demoralization” or that indolence was not an original trait of the Cubans.

We are five siblings by mother and father and one born out of wedlock. Not all were born in Cuba. Of them, only I live in Cuba. The rest went to the United States and elsewhere. Now they are all in the United States. My brother Pepe [José J.] was the only one of us who studied History and collaborated with my father in the book Guerra, migración y muerte. El ejército español en Cuba como vía migratoria.

My husband, Tito Díaz Bravo, is a chemical engineer, but he almost always works as a calculus teacher. Now you see him arriving on his bike, in search of survival. My son Rogelio, a physicist by training like myself, works his butt off in a medical clinic in Córdoba, Argentina. My daughter, Beatriz, also studied Physics and works in Canada in her profession.

The house where we live now is not my parents’ original one. We swapped that one to get here. In these bookshelves are his books and his things. I am asymptomatic in terms of order, I have my disorder, but I find everything in the middle of it all.

The character

My father always bet on what was fantastic. To the fullest. That led him to make his mistakes. He believed, for example, that in the sugar mills, the slaves could not create and support a family. He was convinced it was impossible. However, María del Carmen Barcia, Aisnara Perera and María de los Ángeles Meriño have shown the opposite, with much documentation, with data on marriages found, for example, in church archives.

Dad was the owner of the absolute truth. As a physicist, I know that knowing what came next with Einstein and Schrodinger does not detract from Newton, although they contradict him in part, but my father was very passionate about his ideas. I’m not offended if he is challenged.

He knew how to handle himself socially very well. With the ladies, he knew how to do it very well. He loved being, living, feeling modern. When nobody wore sandals, he wore them, without socks, with shorts. He was very careful about showing himself. Many women considered him a handsome man. He spoke with tremendous elegance.

He was a believer. He believed in the God of the Catholics. Not in the sense that God has about who knows how many virgins near him, but I’m convinced he believed in God.

He used to say he was a good runner. I laugh with his things. Yes, he ran long distances. He certainly liked it a lot and did it all the time. In pelota he was incredibly bad. He also liked soccer (I don’t quite remember whether American or Spanish, but he liked and talked about that sport). He also appreciated chess.

He studied some painting, but it was only because my grandmother wanted to get him and his brother Elpidio off the street during Machado’s time. He was born in 1920 and was a teenage boy in the midst of the crisis of that tyranny. They were enrolled in San Alejandro. It helped my father to get to know the artistic environment and to make friends, but not to paint, in which he was rather bad.

[Oscar] Zanetti has said that he was a member of Triple A for a time―the anti-Batista organization created by Aureliano Sánchez Arango―but I don’t remember that. I was very little then. My sister Eugenia, older than me, does remember Aureliano Sánchez Arango. She says that, physically, in her memory he resembles the mayor of San Nicolás del Peladero (Enrique Santiesteban).

Dad always read a lot of poetry and made us read it. And to learn it by heart. Once he wanted me to learn Platero y yo by heart.

Friends

He was also passionate about his friends. Mario Arancibia, the Chilean singer, one of the best-remembered bolero musicians of the genre’s golden age, was one of his closest friends. They worked together on Radio Continente, in Caracas. They made radio soap operas, the kind in which people cry a lot. Mario’s wife was an actress in them.

In Cuba, Pepe Guedes was close to him. We called him uncle, because of the familiarity with which he treated us. Their friendship also came from the time in Venezuela.

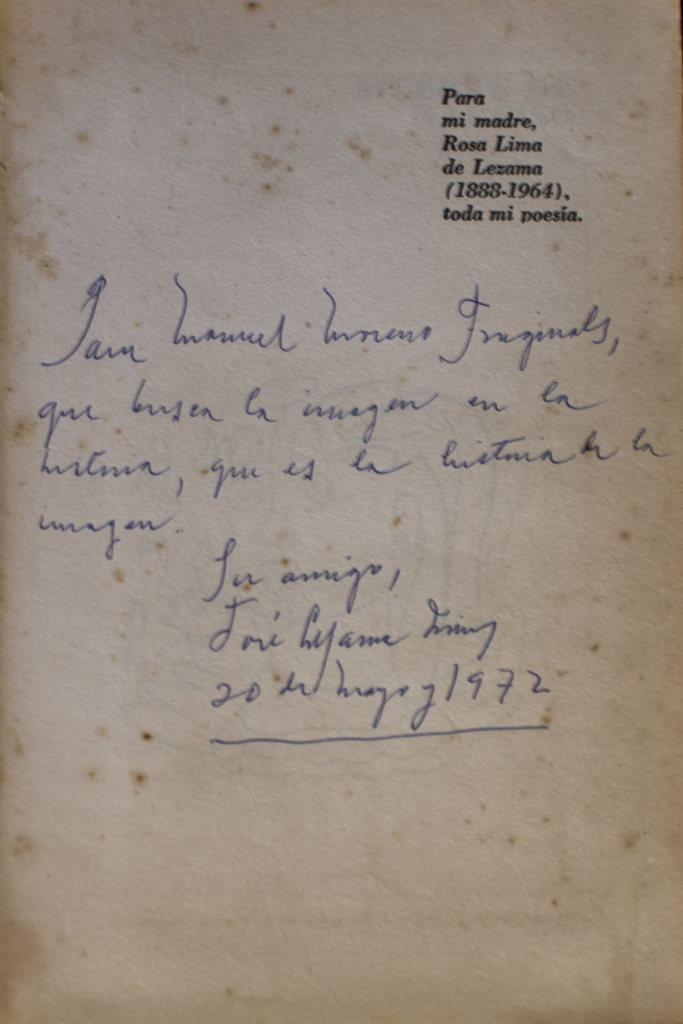

Dad was also a good friend of Cintio [Vitier], [José] Lezama [Lima], Eliseo [Diego], Fina [García Marruz], of the entire group at the José Martí National Library, who, of course, came from Origen. They were his strong partners, as young people say now. So were Odilio Urfé and Argeliers León.

Likewise, his friends were Father [Ángel] Gaztelu, Bishop Carlos Manuel [de Céspedes y García Menocal] and Jaime [Ortega], who was cardinal. And among the people who were younger than him, Reynaldo González. I’m sure there are more, but these are the ones I remember right now.

Specifically, my father and Lezama were great friends. The prologue to Oppiano Licario emerged from that friendship. In that text, father says that Lezama had a six-hour-a-day job, which the poet used to organize and study files of common prisoners who were serving time for theft, scandal or prohibited gambling.

As you can see in this prologue, my father was infinitely astonished at how in the midst of all this Lezama wrote “the source of the most exquisite poetry: Cautivo enredo ronda tu costado/nevada pluma hiriendo la garganta….” That’s why he says here that the power of isolation between the surrounding reality and the inner world was very characteristic of Lezama.

When my father had cataract surgery, I don’t remember if it was the UNEAC or some other institution, he booked a reservation at Los Jazmines Motel, in Viñales, for 15 days. It was known that if they left my father in Havana, he would immediately take to the streets and the operation would have been a disaster. My mother was working. So we went to Los Jazmines, Lezama and María Luisa [Bautista de Lezama], Dad and me. At that time, there was a university activity, from the Physics faculty, to go to work in the fields. The trip was my justification for not attending, but it was the only time I missed one of those things back then.

In Viñales, Lezama and dad spent the whole day doing what I like to call “gossiping,” that art of speaking ill of everyone, specifically of other intellectuals. Don’t think that Lezama talked about it like he wrote poetry. Nothing of the sort. Gossip is always understood. His was very understandable. I would leave them to it and go to the pool.

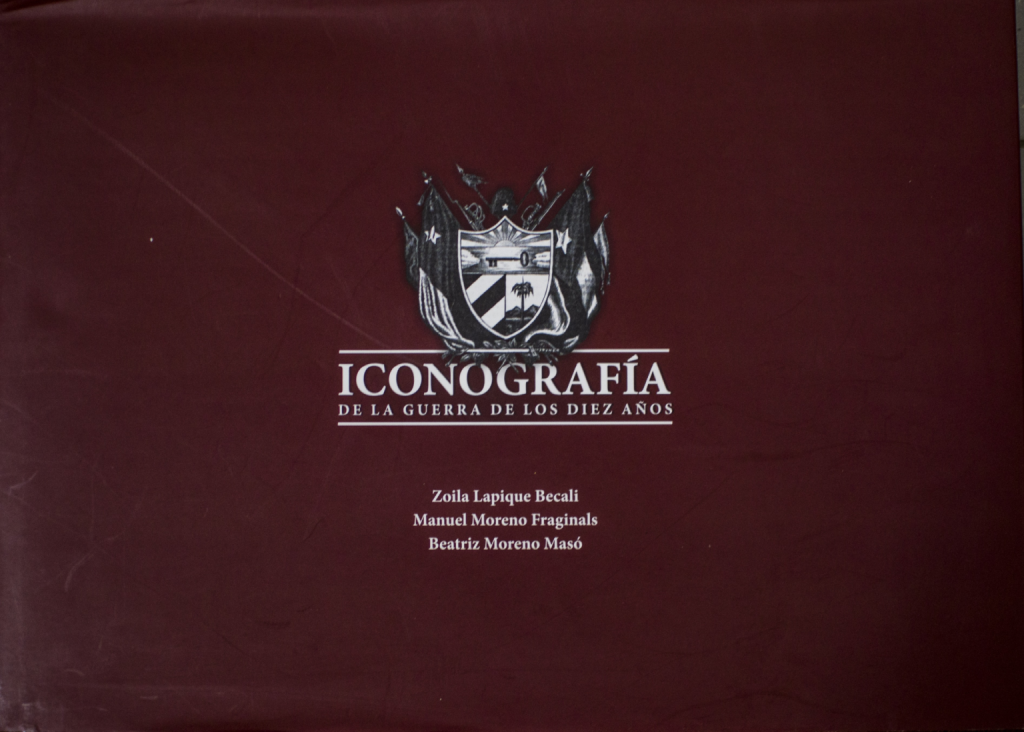

Dad was a good friend of [Tomás Gutiérrez] Alea. My father was the one who discovers the anecdote from La última cena. Alea recreates it narratively. Zoila Lapique was a great friend and was always his right hand. Zoila’s memory is the greatest thing in life. She is one of those historians that if she tells you that there is an engraving on the commerce of Havana, in such a year of the 19th century, in such a magazine, go there and it will be there.

My father left unfinished a book that thanks to Zoila’s work, and mine, we were able to publish. It is entitled Iconografía de la Guerra de los Diez Años.

Odilio Urfé, the musicologist, whom I already mentioned, was another of his best friends. Urfé gave a real “nuisance” at home. He had lunch, supper, they talked. They didn’t know when to end their talking. We had an electric piano at home. Urfé used to play music from memory. Between one piece and the other, they spoke a lot, critically, about the National Council of Culture. In the case of Urfé and my father, the gossip covered mainly the music sector, but the ICRT was not unscathed.

Dad had a formal position in the National Council of Culture, but it was like an advisor, without a real presence or decision-making power.

Adversaries

About his critics and enemies, I don’t know what to say. My father liked to “play the victim” a bit. He said that he could not enter the University of Havana. It was true, he had many conflicts with that group. Sergio Aguirre and he could disliked each other. I have heard that Aguirre boasted of never having entered a file. I can’t be sure of that, but I do know that my father was a file man morning, noon, and night.

However, here among us, he also said that he was not allowed to enter the Institute of History. As part of my job, while I was at the Higher Institute of Art (ISA), I had to go several times to the Institute of History. An administrator called me one day and showed me a letter that was yellow because of the years, which consigned the express invitation to my father to work with their collections.

Maybe what my dad said had ulterior motives. I don’t know. In any case, my father was a man with a conscience and knowledge about the role of drama, and perhaps he also dramatized his adversaries.

With Julio Le Riverend he had a certain reluctance. It’s true. Le Riverend obtained the scholarship from the Colegio de México. My father and Carlos Fontanellas also requested it. Dad, not knowing the outcome of the scholarship decision, caught a plane and left for Mexico. Like a “barbarian” he took off. The Colegio authorities decided to divide the small amount of the scholarship between Fontanellas and my father. The rest of what was necessary to live off of they would have get on their own. Dad and Le Riverend, sometimes, hated each other’s guts, but then on Sunday we went to the birthday of Adita, or Lochy, or Julito, Le Riverend’s children.

My father spent some time at the Universidad de las Villas, another at the Universidad de Oriente, but his greatest teaching work was at the ISA, which he eventually left because he was already old, he traveled a lot and his commitments there were an impediment for him. However, he left many students at ISA and had a good space to work.

Business, and statistics

Dad was delved into many types of work. The Caracas brewery, in the 1950s, “caused” him to become obese, since the cases of beer and malt came home by the ton. As I said, he worked on radio soap operas, but also on the organization of shows. When Benny [Moré] went to Caracas he was involved in the organization of his show.

Moreno, as they call him, became the owner of Radio Junín. It seems that on one occasion they swindled him, and to compensate him they gave him that radio station. When we all arrived in Venezuela, we went to that small town, called San Cristóbal. Today it is a much larger city, and, by the way, very conflictive due to the traffic with Colombia. Smuggling was very common at the time―and still is.

There I also found out that the horoscopes were made by two people (my dad and a collaborator), at a table, inventing them from beginning to end.

We lived in San Cristóbal for a year, more or less, until the revolution triumphed in 1959 and we came to Havana. Dad sold Radio Junín and sent his already born children here. When he sold the station, he sent the furniture from the house by ship to Cuba and met with us.

In all his work wanderings, he learned a lot about finances. Unlike many humanists, my dad understood math. Here I have econometrics books with which he worked. He handled a lot of data and information and was capable of processing them. That is why he was able to process so much statistics on the global and Cuban sugar markets later.

A new book by Moreno Fraginals

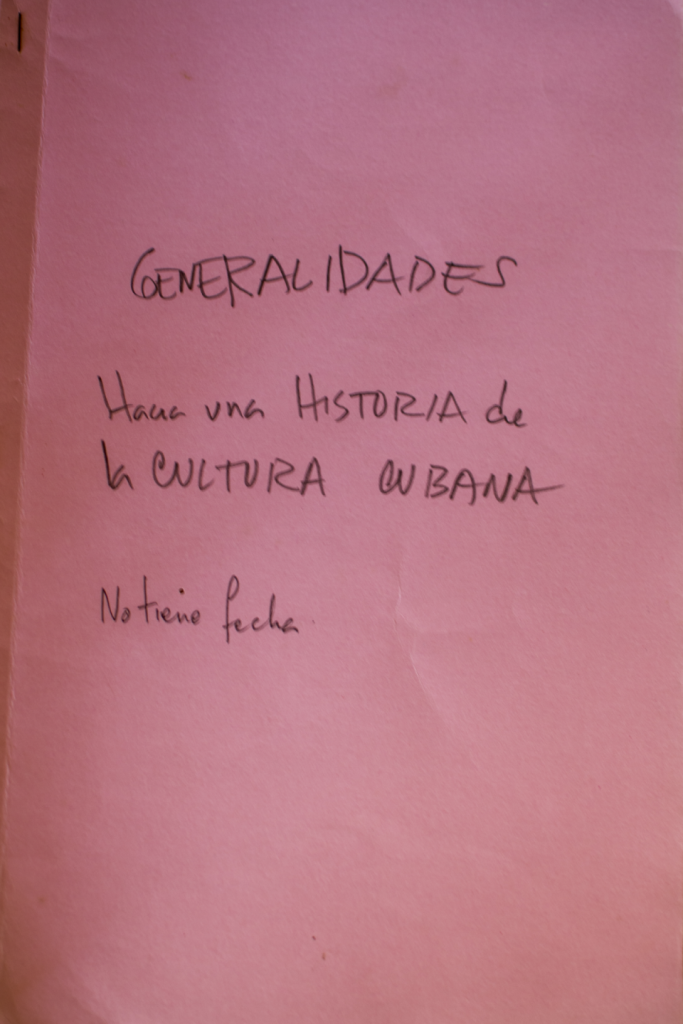

Of the work at ISA, his project on the origin and development of Cuban culture was crucial. In those materials, by the way, you can find quotes from poems by Eliseo.

Hilda Vila, then very young and who had recently graduated from History, collected his postgraduate speeches and in other spaces at ISA. She recorded them on cassettes. Hilda was a devotee, I have no other word to describe her, of my father’s work. They are non-professional recordings, with jumps and indecipherable phrases, but the bulk is preserved, thanks to her.

Those typewritten materials, the old ones, were digitized by me, and corrected to the best of my ability. In addition, I incorporated some materials, mostly unpublished, that rounded out some aspects that were, let’s say, a little in the air.

It will be a forthcoming volume by Ciencias Sociales publishers. It begins with three writings where the conceptual part is developed and then twenty-two chapters, ranging from the Indo-Cubans to the beginning of the revolution.

Exile

My father left Cuba at the age of 75. My brothers had already left. This is part of the thorny topics, which I prefer not to talk about much. Everyone in the intellectual world knows this and there’s nothing new here.

When my parents leave, they say to me: “Tici,” that’s me, “we will come back, but…then what will we do for the daily stuff?” I told my brothers to send me some money monthly and that I would take care of them both when they were here again. That was in the very tough 1994. But my parents didn’t come back.

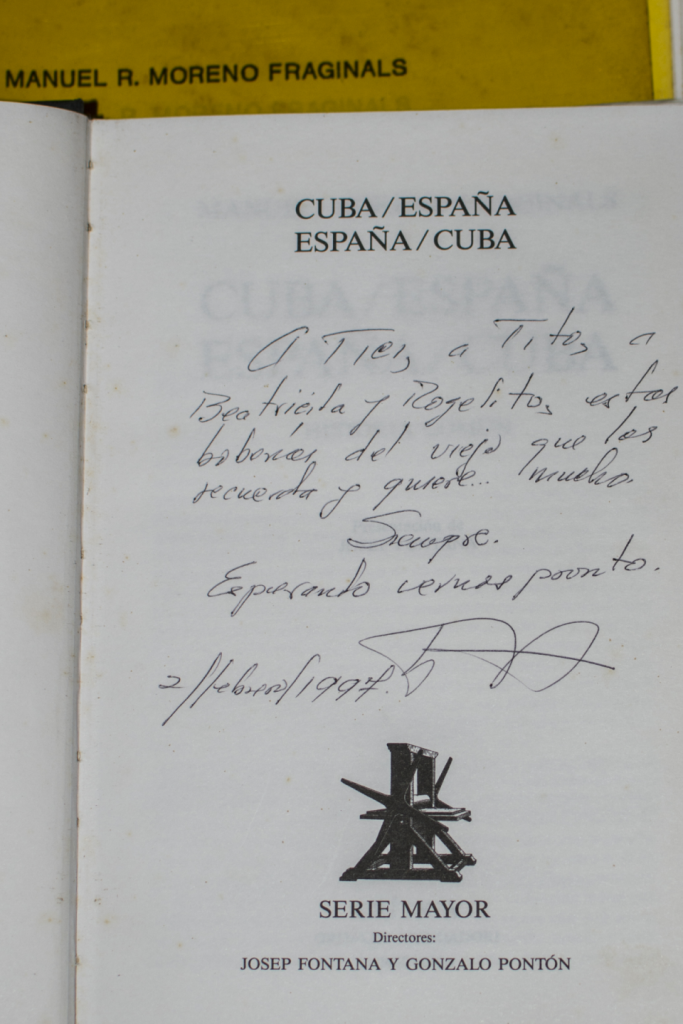

While there my dad was infatuated. His new wife demanded that he divorce my mom. In Cuba España/España Cuba he mentioned his new wife as a collaborator.

Now, when they tell my father that they are going to publish that book, he asks me (over the phone) for the 3 ½ diskettes―that technology back then―and I sent them to him. The edition soon came out. Surely they made changes to it, as part of the editorial process, but I know that the book already existed before he left Cuba.

Since before he left, over the years, my dad had started losing his vision. That prevented him from driving in Cuba, so in Miami that couldn’t even cross his mind. He lived in Coral Gables and gave some classes or talks at Florida International University. The accident that ultimately causes his death is related to loss of vision.

He goes out (already living in the new wife’s house) to pick up the mail, falls and breaks his hip. After the operation, his blood pressure rose and the thrombus formed that would be the beginning of the end. He was 81 years old when he died (2001). He could have done so much more. José Luciano Franco and Ángel Augier at that age, and more, kept doing things.

The then United States Interests Section in Havana and the Cuban authorities in a week arranged for my visa and all the necessary paperwork to travel. I was able to see him in bed. His remains are in Miami, but I don’t know where. I’m an emotional hypertensive. I’ve been to that city a lot, but I haven’t even wanted to find out where it is, much less go to his grave. What I do is remember him in my own way, working and publishing his stuff.

The memory of her father

My father and I never argued about politics. Absolutely not. He cared a lot about us. He told us to have a lot of confidence in ourselves. About his moral formation of us, I always remember him saying:

“It’s necessary to work a lot.”

You haven’t asked me about this, but I’m going to tell you: He was a loving father.

Moreno Fraginals, a Cuban-Caribbean vision of the world

A comment by Joan Casanovas Codina

1.

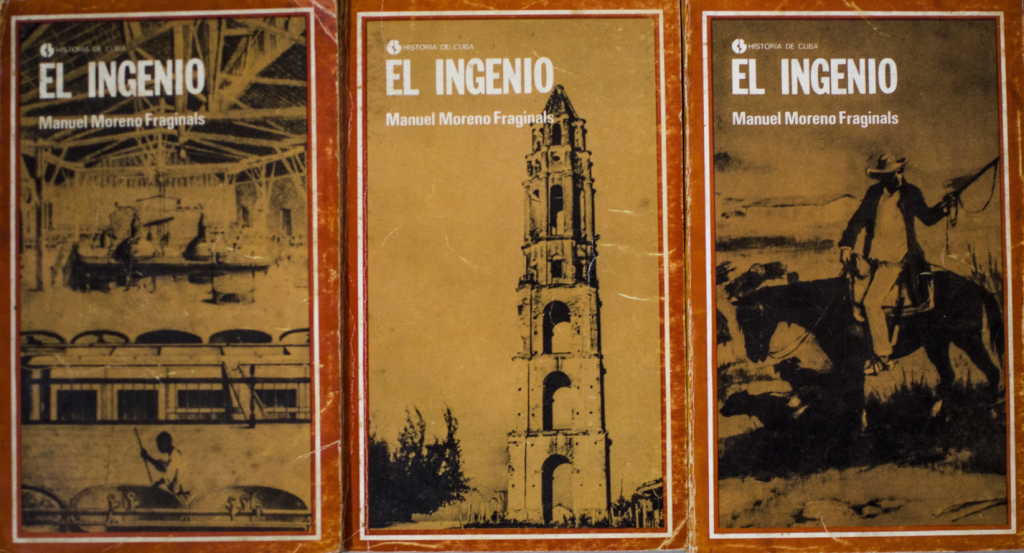

When reading the first paragraph of Moreno Fraginals’ best-known work, El Ingenio, the reader perceives that it is a great history book.

When I first read it I was studying at Stony Brook University, a public university in the state of New York. Post-graduate students in Latin American history read the works of many U.S. authors. Fortunately, Professor Barbara Weinstein, who would later direct my thesis on Cuban history, assigned us to read several Latin American authors. This is how we read El Ingenio (edited by Monthly Review, in 1976), in an excellent translation that Cedric Belfrage made of the Spanish edition (UNESCO, 1964).

I remember that I liked reading a work written in a style that, due to my European origin, was very familiar to me. However, at the same time El Ingenio was a work in which I found very novel points of view and forms of expression. It was this second aspect that captivated me the most.

After reading a few pages, Moreno Fraginals had already immersed me in his Cuban-Caribbean vision of the world. Since then, I have periodically re-read this work, whether in the 1964 edition, or the three volumes of the 1978 edition. I like it because it makes the reader feel the social universe that surrounded the sugar boxes that moved the Cuban economy.

Moreno Fraginals makes us feel the breath of the people who lived in this world of the past. At the same time, he writes inside a very flexible and innovative historical materialism that allows us to understand how the material environment and technology accompany a process that people promote.

As explained by his professor and friend Josep Fontana, this led Moreno to experience some setbacks in Cuba. There were those who defined him as a “not very Marxist” historian, with what this meant in Cuba at that time.1 Fortunately, time puts everything in its place. To this day, the most important work in Cuban historiography in recent decades continues to be El Ingenio.

By the way, I find it useful to recall a detail of interest in Moreno’s friendship with Fontana. Moreno, familiar with his colleague, knew that his name was pronounced Josep, which is how it is written in modern Catalan spelling. However, in the second volume of El Ingenio, Moreno quotes Fontana writing his Christian name as “Joseph,” that is, with the Catalan spelling before the 20th century. Without a doubt, he did so due to the fact that, during Francoism, the State did not allow writing proper names in Catalan.

But where does Moreno’s ability to observe and reflect in such an agile way, as well as erudite and interesting, come from? It is well known that science (whether in the physical or social world) is a constant interpretation of ever-changing reality, using evidence and arguments as strong as possible. However, if we remember Plato’s example of students who are locked in a cavern (The Republic, Book 7), we understand reality as an object of which we only see the shadow, the silhouette, either in an atomic microscope or in the text of a historical document.

Therefore, if we only see shadows, the main problem of science is not how to delimit them as much as possible, but to decide which are the shadows that we must observe, analyze and explain.

In this sense, the initial step of historians, or of scientists in general, rather than being a purely scientific act, is the result above all of their social, artistic and ultimately literate, scientific culture. In all these aspects, the domestic and family environment, his affective world, his world as a person who truly lives in this world, are important.

By understanding what is known as the historian’s “private life,” we can better understand why Moreno is a great historian, why instead of writing a merely economic, or economistic, account of the history of Cuba, he constructed a socio-economic, cultural, and also technological, interpretation of great depth, historiographic precision and linguistic style. A work that, in addition to impacting the field of research, even inspired films of the artistic quality of La última cena, by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea.

Thanks to the vision offered by the interview of Professor Julio César Guanche with the historian’s daughter, we can better understand how Moreno’s effort and ability managed to make Cuban, Caribbean and Latin American historiography take such an important leap forward that it is still in force.

2.

A second point to underline in Moreno’s work is that he understood the colonial context as a network of economic interests and political loyalties, which moved within the framework that delimited the very old former metropolis.

The historian never accepted to give a stereotyped and superficial vision of the history of Spain. Using the language of the English historian Herbert Butterfield, we can affirm that Moreno flatly rejected any “Whig” (that is, “teleological”) interpretation of Cuban history.

Moreno won the game, because these types of historical interpretations have now almost totally disappeared, either in relation to the colonial past, or to the post-1898/1902 republican stage.

In this last stage, the Spanish colonial presence formally disappeared, but, contrary to what some may think, it maintained a certain presence in an indirect way, due to the limitation to Cuban sovereignty that the United States imposed for decades, whose government managed the change of sovereignty and dominated fundamental aspects of republican life.

Therefore, to understand 20th century Cuban history, the vision that Moreno contributed in relation to the former metropolis is also necessary.

3.

Finally, I sense that if Moreno were to witness how digital technology currently revolutionizes our social, intellectual world, etc., instead of falling into a very materialistic reduction, he would side with those who affirm that technology only satisfies social demands in general, but also those of the political and economic elites. Moreno would observe the material environment based on the social and cultural context in which we live.

Welcome, then, the work of Manuel Moreno Fraginals to the 21st century.

***

Note:

1 See Josep Fontana, “La historia de los hombres,” Editorial Crítica, 2001, p. 236.

Muchas gracias por tan bello articulo y gran apreciación de la vida y obra de mi padre. Me gustaría poderlo incluir en la pagina web que he creado en su honor. Saludos