1

The Alien and Sedition Acts were passed by the United States Congress in 1798 during the administration of President John Adams, amid a possible war and fears of a French invasion.

Now that the topic has returned to the fore, it is useful to recall certain tangencies with the present. The Federalist Party, which championed a strong executive, was then the dominant force in U.S. politics when Adams won the election. He was the second president of the United States, after George Washington (1789-1797).

Grouped in the Democratic-Republican Party, also known as the Jeffersonians — a precursor to today’s Democratic Party — their opponents advocated giving more power to state governments, accusing the others of preferring a monarchical style of government.

The former accused the latter of conspiring with France against the United States government. One of the nation’s Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton, deeply anti-Jeffersonian, wrote that they were “more Frenchmen than American” and were prepared, literally, “ to immolate the independence and welfare of their country at the shrine of France.”

Because of these laws, the government could then arrest and deport any citizen of an enemy nation in the event of war. And do the same to any non-citizen suspected of conspiring against the government.

Most of those laws have expired or have been repealed over the years. The Alien Enemies Act has now been rescued and recycled from the couch by MAGA ideologues after more than eighty years of inaction.

2

The president can invoke the Alien Enemies Act in the event of a “declared war” or when a foreign government threatens or carries out an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” against U.S. territory.

Legal experts and historians point out that in the Constitution and other documents from the late 18th century, the term “invasion” was used literally and typically to refer to military attacks. And that “predatory incursion” was used literally to refer to smaller-scale attacks, always within the military sphere.

The Constitution grants Congress, not the president, the power to declare war. Therefore, the president must wait for a debate and a vote in Congress to invoke the Alien Enemies Act in the event of a declared war.

However, the president does not need to wait for Congress to invoke the law in the event of an “invasion” or “predatory incursion.” He has the authority to repel sudden attacks, which implies discretion to decide when an invasion is underway.

This latter is the spin that Stephen Miller, White House deputy chief of staff, and the Trumpists have given the term; that is, the country is being invaded by foreigners: immigrants. They have repeated this over and over again, before and after Trump’s executive order, paving the way for the landing.

But critics of that decision maintain that it can only be used in the event of “a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion.” The United States is not at war with Venezuela. And there has been no “invasion” in the military sense of the term.

Since then, the Act has been invoked only three times: during the War of 1812 against the British, World War I, and World War II. In the second case, the Woodrow Wilson administration (1913-1921) defended its application by saying that non-citizens with connections to a “belligerent alien” could be “treated as prisoners of war.” This was a defining element in the detentions, expulsions, and restrictions against German, Austro-Hungarian, Japanese, and Italian immigrants.

The third case is perhaps the most famous: the forced internment of Japanese in isolation camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor (1942), dubbed “relocation centers” by the Roosevelt administration; an episode in U.S. history for which even Congress, several presidents, and the courts have apologized.

3

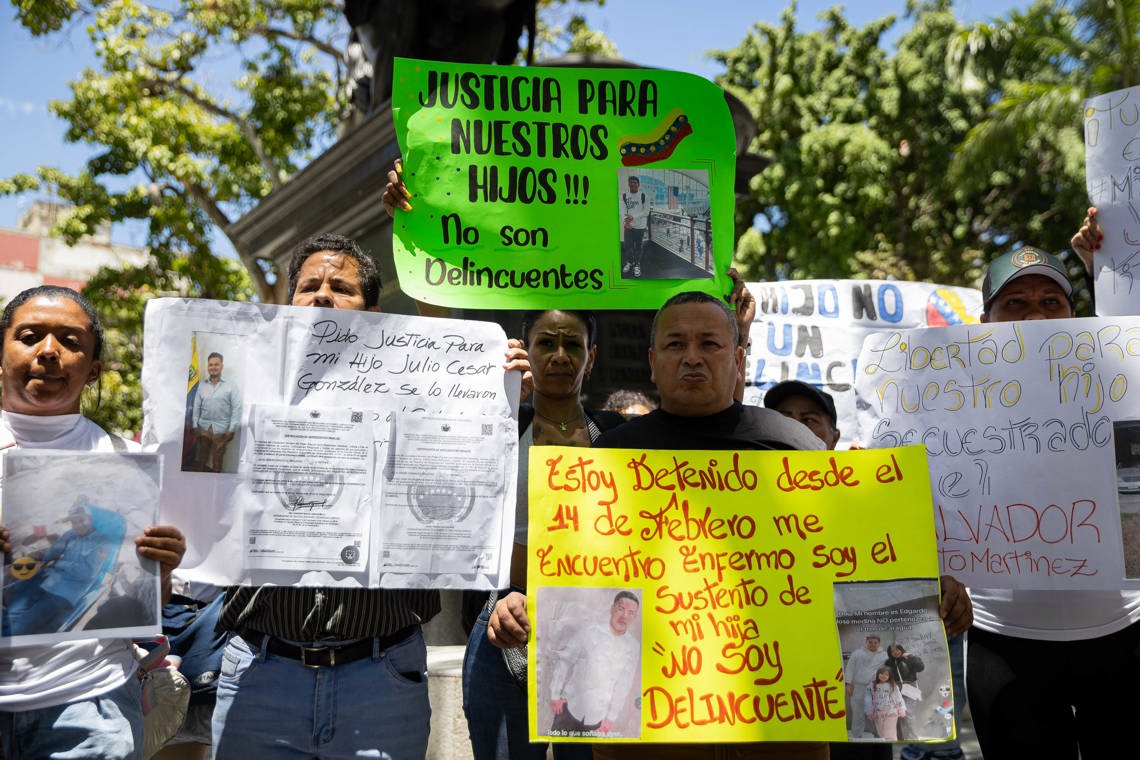

In the early hours of March 15, Donald Trump issued a proclamation ordering the immediate apprehension, detention, and expulsion of Venezuelan citizens over the age of 14 who were members of the Tren de Aragua.

That same day, 240 alleged members of that criminal organization were deported by air to a mega-prison in El Salvador, one of the results of an agreement with Nayib Nukele during Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s tour of several Central American and Caribbean countries.

Reacting to a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), federal judge James Boasberg issued a verbal order to the government to turn around the flights carrying the deportees. “This is something you must ensure is carried out immediately,” he told the Department of Justice.

But the White House did not comply. It said it was too late because the planes were already in international airspace, near Yucatán. “We believe the order is not enforceable,” stated a senior administration official. Trump’s advisers argued that Judge Boasberg had exceeded his authority by issuing an order preventing the president from deporting these alleged Tren de Aragua gang members under the Alien Enemies Act of 1789.

According to reports, Miller orchestrated the process in the West Wing with Homeland Security Secretary Kristy Noem.

Following the traditional rhyme, they moved to politicize everything. “If the Democrats want to argue for returning a plane full of rapists, murderers, and gang members to the United States, that’s a fight we’ll gladly take,” said White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt.

It is unclear how many of those deported under the Alien Enemies Act were actually from the Tren de Aragua gang. In other words, it is unknown whether all of them were gang members and terrorists, as the administration has defined them.

4

Boasberg rebuked government lawyers by questioning their invocation of rarely used powers to deport people, in this case Venezuelans. He confronted the Justice Department lawyer at a hearing in Washington, D.C., saying he was not accustomed to such “disrespectful” language in government documents.

He also said he agreed that the president had “wide latitude” to enforce immigration law. But he expressed reservations about whether the deportees had legal recourse to challenge their membership in the gang. Boasberg asserted that the political ramifications of this are incredibly troubling and disturbing.

Finally, he dismissed the government’s arguments, calling them woefully insufficient.

Then the expected happened. Trump called for the judge’s impeachment. Without mentioning him by name, he said that this judge, like many of the corrupt judges before whom he is forced to appear, should be DISMISSED! He also called him a “radical left lunatic,” a troublemaker and agitator who, unfortunately, was appointed by Barack Hussein Obama.

But that broadside led to an unusual development. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts issued a written statement that, in effect, functioned as a corrective: “For more than two centuries, it has been established that impeachment is not an appropriate response to disagreement concerning a judicial decision,” Roberts said. “The normal appellate review process exists for that purpose.”

A miscalculation by the president. This is a highly respected judge and former prosecutor. Prior to this incident, he was appointed by Roberts himself to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a top-secret body that reviews federal government requests to monitor foreign intelligence activities in the United States.

On the other hand, the judge maintains longstanding ties with both conservative and liberal colleagues, having lived in the same residence as Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh while they were studying at Yale Law School.

With this, politicization has, in fact, been dealt a blow to the forehead. However, not in the narratives used to further enforce this law: White House National Security Advisor Mike Waltz declared on CBS’s “Face the Nation” that the Tren de Aragua group was an agent of Nicolás Maduro’s government. “The Foreign Sedition Act fully applies because we have also determined that this group acts as an agent of the Maduro regime,” he declared. “Maduro is deliberately emptying his prisons in a proxy manner to- to influence and attack the United States.”

5

This case is just the latest in a series of clashes between the administration and federal judges seeking to block actions that range from controversial to illegal.

The dead stops are motivated by a wide range of issues, from the president’s national security powers to the dismissal of tens of thousands of federal employees at the Pentagon, the Department of Justice, and other agencies created by Congress that are supposed to be independent.

Officials like Tom Homan, the “border czar,” are poised to further strain that tension with open challenges to the judiciary. “As far as this case is concerned,” he said, “I don’t care what the judges think. We won’t stop arresting those who threaten public safety and national security. We won’t stop deporting them from the United States.”

And he added that regardless of what he [Judge Boasberg] thinks, they will continue to target the worst of the worst, as it has been done from the beginning, and deport them from the United States through the various laws that are in place; we are not making this up, the Alien Enemies Act was, in fact, a federal law enacted by Congress and signed by a president. That’s our legal dispute.