“Cubana de Aviación announces its flight from Buenos Aires to… Havana!”

For a couple of years now, I have imagined those words, with an Argentine accent, coming from the loudspeakers of the Ministro Pistarini International Airport in Argentina.

It is not necessary to consult Freud to know that my desire to feel again the sensation of traveling (not to any destination but to Cuba) is rooted in the forced immobility that COVID-19 brought us.

A few days ago I finally boarded a Cubana de Aviación plane and landed on the island. Contrary to my fantasy, when I arrived at the airport there was no high-sounding voice announcing my destination. Neither information screens indicating the counter where my flight was being checked.

![]()

None of that was needed. There it was, well in sight, the line for Cubana de Aviación flight 361, bound for Havana. The unequivocal proof was that the line of passengers looked like a giant snake, zigzagging through the immense hall, with packages of all shapes and sizes as if that scene were an artificial mountain system inside the airport.

None of that was needed. There it was, well in sight, the line for Cubana de Aviación flight 361, bound for Havana. The unequivocal proof was that the line of passengers looked like a giant snake, zigzagging through the immense hall, with packages of all shapes and sizes as if that scene were an artificial mountain system inside the airport.

I made it almost to the far end of the line. Shortly before, my friend Leandro was patiently waiting for me and had marked for four people on the line. In other words, there were still two more friends to arrive, Yuri and Amado.

None of them would travel. The passenger was just me but Leo was carrying a wheelchair for his grandmother in order to dispatch it with my luggage. The other two friends, who were not traveling either, brought a couple of suitcases loaded with food, toiletries and medicine, which would also be part of my luggage.

At that point, I was loaded with four large and one small suitcases, a wheelchair, and a backpack with my photography equipment. As established by Cubana de Aviación, on this flight from Buenos Aires to Havana, Cubans are allowed to carry two suitcases free of charge of 30 kg each and another paid as excess baggage.

Applause for the national airline, which is often the target of criticism and memes. But it should be noted that in these unfortunate times, it has implemented measures to facilitate access to tickets for Cubans residing in Argentina with discounts and, also, with the transportation of food, medicine and toiletries for the Cuban family.

“There are four of us,” I told the man who was behind us on the line, so that there would be no misunderstandings, because in every “respectful” line of Cubans, from one moment to the next others appear to cut in. My interlocutor raised his eyebrows and resignedly accentuated with his head that everything was fine.

And then, a lost lady asked me if I was “the last one” for Havana. “No, you have to go round that column and you will see that the row is still there,” I replied. I look at the horizon without finding an end and only heard her say “candela!” as she walked away.

In that scenario, I doubted for a second if I was waiting for the P1, at 23 and K, or the Cubana plane, in Buenos Aires.

Another issue is that, while waiting for the line to advance, this is used to organize and reorganize the packages. When Cubans travel abroad, they are constantly concerned about their excess baggage.

Traveling everywhere loaded is one of the karmas of Cubans. Our trips are not calculated in the time that a flight can take from any city in the world to Havana. That journey has been counted for months before, in which dissimilar things are being obtained to take to the island. From food, medicine and toiletries to the slapdash articles or the most unusual request from a family member.

In that spending hours in an airport line for a flight to the island, another distinctive feature of the fact that the vast majority of those protagonists are Cuban passengers is that the Cuban accent is heard in the middle of the murmur. That Cuban talking is like a soundtrack, the “cubaneo,” an encompassing popular term and not yet recognized by the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), that describes when a group of Cubans abroad is exacerbated by means of gesticulations, greetings, smiles and grammatical constructions in the style “que bolá” … “en la lucha” … “let’s see if I can send a small package to the pura.”

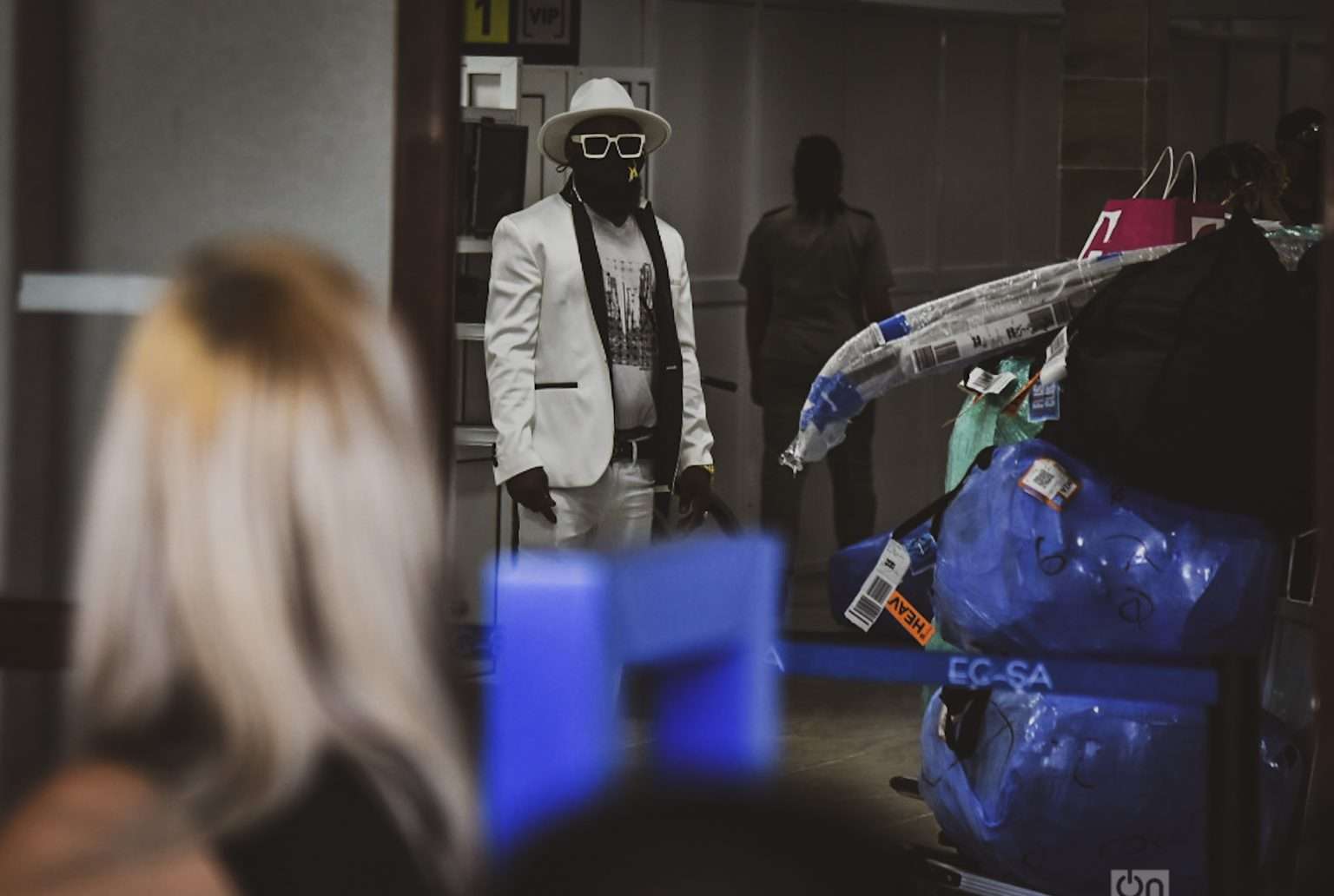

And then that charismatic character always appears, who greets everyone at the top of his lungs even if he doesn’t know anyone. That Cuban has been living “a bunch of years” outside of Cuba but he gets to a lines and feels in his environment and “at his own pace.” The main thing for him is that everyone in that place knows that he is Cuban. In this way, he displays his talents as a conversationalist and spends a while with this one and a while with the other. He makes jokes and talks about all the issues concerning national events. He will talk about how the Cuban economy is, as well as the latest showbiz gossip.

As time passes on that line, which does not advance, Cubans, patient and accustomed, remain serene. The one who is not Cuban, the one who goes as a tourist to Cuba, is immediately noticeable because, simply, he despairs and does not understand that that line, which remains almost static, where they shout “the last oneeeee,” is already part of the experience to be on the island.

The line, with all the attributes that distinguish it as an authentic Cuban line — even to check a flight —, whatever the airport, is a Cuban territory.

Kaloian Santos Cabrera

With a Soviet Zenit camera, some money and a bag holding more illusions than clothes or food, I started traveling with my backpack through Cuba when I was 18 years old. Photography and journalism then appeared as a need and would become for always a form of militancy.