In 1967, at the age of 21, Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio Rodríguez composed “La canción de la trova,” which goes like this:

Although things change color, /it doesn’t matter as time goes by, /things tend to change /always while walking. /But behind the guitar there’ll always be a voice /more seen or more lost /due to the lack of understanding of being one who feels, /as it also was in another time it.

There are also hearts that today feel stopped. /Although there are other times today, /and tomorrow it will also be: /we continue talking with the sea.

Although things change color, /it doesn’t matter as time goes by, /the word doesn’t matter / when loving words are said, /because as long as it’s sung from the heart /there’ll always be an attentive sense for the emotion of seeing /that the guitar is the guitar /without aging.

This theme is almost 55 years old, included in Silvio’s sixteenth album.

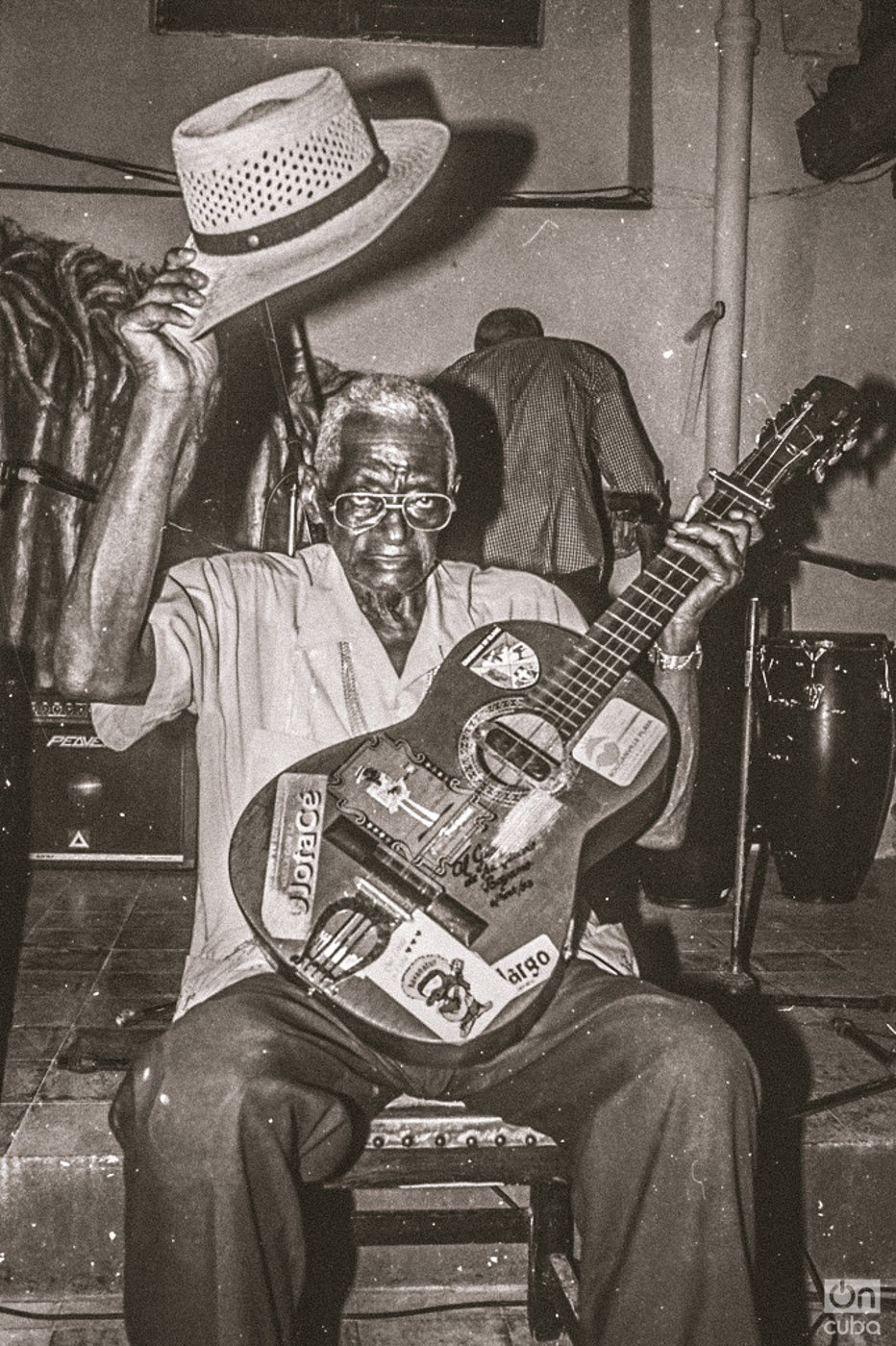

These days, while going through old photographs, those I took almost a couple of decades ago when I was walking around Cuba with an old Zenit film camera, I found in some snapshots those troubadours that Silvio mentions in the previous verses.

Perhaps my incurable fondness for music made me focus on those wandering bards that I once came across in a house, a street, or a park in Cuba, heirs of those who centuries ago created the trova and the bolero, like Pepe Sánchez, Sindo Garay, or María Teresa Vera.

Perhaps my incurable fondness for music made me focus on those wandering bards that I once came across in a house, a street, or a park in Cuba, heirs of those who centuries ago created the trova and the bolero, like Pepe Sánchez, Sindo Garay, or María Teresa Vera.

Like those inescapable references to Cuban music, the minstrels in these photos, scattered over time, walk carrying their songs on their backs. They sing to the joy of love at its fullest, but they also sing to the pain when feelings are on fire.

The themes on which they are inspired are almost the same throughout the ages and never run out because precisely the most wonderful compositions are always born from a life explored in all its nuances.

Thus a personal experience can be transformed into a song. This sublime act is, in turn, a collective feeling that transcends time.

Although the companion of the six strings is always the protagonist and the eternal lover of the troubadours, some, in addition, are accompanied by the traditional double bass, the guayo, the keys and even violins.

Usually, these feverish characters are self-taught. Many cannot read the eighth and semi-fuzzy notes of a ruled paper. But, yes, their repertoire is vast and they interpret it from memory. Many dominate, above all, the guitar chords like most musicians, they have impeccable prime and second voices and make of improvisation their own style.

Usually, these feverish characters are self-taught. Many cannot read the eighth and semi-fuzzy notes of a ruled paper. But, yes, their repertoire is vast and they interpret it from memory. Many dominate, above all, the guitar chords like most musicians, they have impeccable prime and second voices and make of improvisation their own style.

The troubadours in these images that I share are those who won’t go to sleep as long as there is someone to sing to. They are unique beings who cultivate and keep latent a primordial part of our Cuban popular culture.

The troubadours in these images that I share are those who won’t go to sleep as long as there is someone to sing to. They are unique beings who cultivate and keep latent a primordial part of our Cuban popular culture.

| Kaloian Santos Cabrera

With a Soviet Zenit camera, some coins, and a bag full of more illusions than clothes or food, I began traveling through Cuba with my knapsack at the age of 18. Photography and journalism then made their appearance as a need and became his form of militancy forever. |