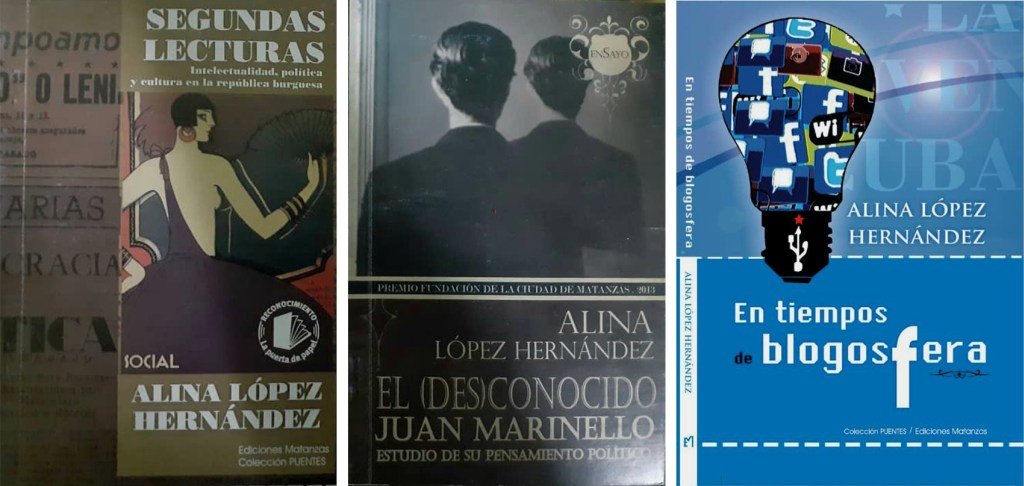

Alina López Hernández (Matanzas, 1965) is a Doctor of Philosophical Sciences and a corresponding Member of the Academy of Cuban History. She has dedicated long years to teaching but her greater visibility as an intellectual is due to her keen participation in the La Joven Cuba (LJC) blog. Alina is the author of the books Segundas lecturas: intelectualidad, política y cultura en la república burguesa (Matanzas publishing house, 2013 and 2015) and El (des)conocido Juan Marinello. Estudio de su pensamiento político (Matanzas publishing house, 2014). She recently presented in her home province her third title: En tiempos de blogosfera,, with the same publishing house, which is a compilation of small essays and opinion articles previously published in LJC.

En tiempos de blogosfera sold out as soon as it went for sale. Its 500 copies “disappeared” in two days. I’m among the lucky ones that got one, which I literally devoured. There I found an infinite number of subjects that are related to me, original and disturbing points of view, a diaphanous prose and an open desire to participate, from academia and theory, in the scrutiny of our contemporaneity. Hence my intention to share with OnCuba readers this fleeting conversation with the author, a prelude (hopefully!) to many others.

What is the role of Cuban social sciences at this time?

Social sciences in Cuba have long been turning their backs on each other. Daughters of a century that, like the 19th, defined rigid objects of study and particular methodologies; they enclosed themselves in compartments and claimed for themselves a part of social reality. It happens, however, that society is one, and complex, and the more it is divided for study, the less rich will be its results.

In the face of social phenomena, always multicausal, multidisciplinary approaches will be necessary. Professor Esteban Morales has addressed this issue several times, I remember an essay he dedicated to the subject.

Another problem is that, either in the research centers of the social field, many of them with great prestige in Cuba, such as in the universities, there are limitations to the investigations that get involved, for example, in the Cuban political system and in citizen participation in it.

Public opinion studies, despite being one of the natural means for feedback that forces governments to have results within a reasonable time, have been seized from the social sciences in our environment. Cuban social scientists cannot conduct mass opinion studies on the government and its policies if they are not “summoned” by it. Even to apply a massive survey regarding the use of free time or reading habits, we must be previously authorized.

As a sequel, university careers that have a social profile: Economics, Sociology, Law or Sociocultural Studies, among others that could advise the government, fail to fulfill their role as diagnosticians and transformers of society. The form of completion of studies and subsequent improvement of professionals in these specialties almost always assumes the modality of “case studies,” a methodology that prevents appreciating trends and generalizing opinions on certain aspects or phenomena.

Added to this are the pressure put on professionals in the social sciences not to publish in alternative media analyzes on topics considered taboo or problematic. Such a situation has even led to some being expelled from the universities and centers where they worked.

The very high qualification that the Cuban educational system provides to these scientists is a true paradox and how the potentialities of their own creation are wasted in something that can be beneficial for the prospective, diagnostic and perspective of Cuban society.

I don’t mean to imply that there are no relevant results in many fields of the social sciences, but I consider that they don’t apply to the extent needed given the great challenges that lie ahead.

Is Marxism still an effective tool for interpreting reality? Do the people who among us defend historical and dialectical materialism as philosophy and social practice fully master it?

The removal of the hyphen between the words Marxism and Leninism, which was approved in the new Constitution, does not guarantee that we will act as consistent Marxists. Only when we subject the diagnosis and prognosis of national news to a detailed critique, when we are able to carry out a complete x-ray of our battered socialism using Marx’s method, will we be in a position to defend it.

It is crucial to check whether the thinking of those who lead the process in Cuba is Marxist as an ideological declaration of principles or if it is based on materialist dialectics as a method. When Marxism is reduced only to its ideological dimension and becomes a state ideology, it is extremely damaging due to the instrumental character it adopts.

A political ideology that tries to present a future of prosperity that is always inaccessible, and that demands loyalty and constant work from its followers, ceases to be liberating and becomes a mechanism of domination. At the same moment in which it is not capable of self-correction, in which it considers itself eternal, it will cease to be Marxist.

In Cuba there is a stagnation of the productive forces, repressed by production relations that are decided at the political level, therefore, without making changes in this sphere, we will not advance. Marxism considers as a law the correspondence between production relations and the character of the productive forces, because when such correspondence is not manifested a path is opened that can determine the transition from one social regime to another.

In the Cuban economy nothing is truly what it seems. Ownership relations, the center of production relations, are manifested as a mystification of reality: socialist ownership is not truly social, since it has been supplanted by a state ownership that is beyond the control of the workers; and private ownership―recognized in this constitution―is not private enough, given the excessive obstacles with which political determinations surround it. Cooperative ownership does not spread its wings despite all the statements and guidelines in the world. This not being really what is intended has brought us to a point of immobility.

Insisting that the eternity of the sociopolitical model was established in an article of the Constitution and not achieving the successful operation of that system is something alien to the Marxist method. The constant appeal to a change of mentality and a revolution in ideas, tries to create the image of progress understood as something inward, and not as the deployment of external forces, and has thus become a philosophy of paralysis.

Certainly, there is nothing as conservative, as subtly demobilizing for societies in crisis, in need of structural changes and profound transformations, than the requirement for a change of mentalities, the rescue of values or the defense of concepts. This would be to reverse the materialistic axiom that people think according to how they live, and to suggest that transmuting thought forms is sufficient for an evolution of material life.

Do you think Cuba is on the verge of a new historical moment?

Yes, I do. A crisis is not such until the social actors don’t take it into account, the subjective factor is determining there. It is a kind of unease of the time, to put it in a way that certain critics will find metaphorical. It is almost always related to the exhaustion of a model, notice that I’m not saying a system.

When we talk about the 1920s in Cuba, we talk about one of those moments. The generation of those years took notice of itself and distanced itself from the politicians of its time. Thus, the political monopoly of the members of the Mambí Liberation Army was broken due to the lack of popular confidence. Batista’s coup in 1952 prompted another of those moments of general conviction in that one had to oppose a state of affairs.

For the arrival at that moment of unease there are, in my opinion, two determining factors today. On the one hand, the inability of our rulers to channel a path of successful reforms. The socialist camp collapsed more than three decades ago and two periods of attempted reforms, one in the 1990s and the other as of 2010, the latter even in a formal way and with a large amount of confirmatory documentation. On the other hand, there is the citizen capacity to submit that disability to public trial, that is something new. The rupture of a one-way information channel allows the alarm signals to be visible. And those who lead know this well but have been unable to respond adequately.

My opinion is that we are witnessing the final exhaustion of an economic and political model, that of bureaucratic socialism. Those who lead do not succeed in advancing the nation with the old methods, but they are not able to accept more participatory forms, with a greater weight of citizens in decision-making.

I think there is a general perception that the Cuban government is managing well the crisis caused by COVID-19. These weeks of forced seclusion and social isolation have brought out the strengths and weaknesses of our State. What would both of them be?

The management of the health situation has shown a well-organized and structured Cuban health system, which knows how to face critical periods and to which the lack of certain supplies can be objected, but which must be recognized that it responded effectively in a time when some economically powerful countries did not do better. Cuba, with a great tendency towards centralization, has experience in positive management of this type of trance.

But the demonstration of weakness in the economy has also been resounding, which does not come from this stage; of scarcity, of the poverty of huge social sectors. Of the lack of protection suffered by many workers who worked as employees in the so-called self-employment sector. The late entry of the Internet to the island has led to services, that would have been very timely now, to collapse in the face of demand. The government’s constant criticism of lines in the markets overlooks a process of deterioration that has been aggravated since 2016, but which last year reached the point of almost paralyzing the country in a situation that is not circumstantial but systemic.

I’m not an economist, but it’s not necessary to be one to confirm that the process of reforms announced more than a decade ago has come to a standstill. That is a weakness that also questions the revolutionary process itself. Let us not forget that the revolution had very precise objectives: national independence and a truly just social policy. Are we financially independent today? I think a Constitution that declares admission to foreign capital and not to national capital should be reviewed, because one of Cuba’s great problems throughout its history has been that geopolitical equation that it has always included, by force or by its own decision, to a traveling companion. Of course, we must have commercial relations with other countries, but depend on another nation, never. That is an outstanding debt.

The state resources put in function of the health sector, and the conception of a highly organized epidemiological system are undoubted strengths that should be maintained and improved. But it is fair to recognize other bastions that have come to light in this situation, although they had already done so on a smaller scale as a result of the tornado that hit the capital last year. They are civic forces and resources not attributable to the State but to society, although evidently they are a complement to it and demonstrate the potential and vitality of civil society. This should convince the State of how convenient the proliferation of associations would be, for which we would have to have less intransigent legislation in association matters than the one that governs today.

Solidarity with just causes, such as the donation of food by farmers to isolation centers, has been demonstrated. Let the animal protection movement continue, without state support and without a legal framework to protect it, trying to rescue, feed, heal and give up for adoption the abandoned animals, many more at this time throughout the country. The fact that some owners of small and medium-sized businesses, members of churches and cultural projects, members of the LGBTI community, compatriots residing in and outside of Cuba, took on the aid of the elderly who live alone and of disabled people is another example.

The role of social networks to channel spontaneous actions that allow creating civic guidelines aimed at locating the most vulnerable, be they people or animals, identifying and prioritizing certain needs and guaranteeing immediate support; it is a lesson for those who only value these platforms as dens of banality.

The State should allow healthy margins of autonomy. I consider it preferable to have a spontaneous, entrepreneurial and autonomous citizenship. Perhaps not as disciplined as it is politically correct, but instead sincerer, more determined to be a true factor of transformation and social improvement. This is not irreconcilable with a socialist project.

What future does the alternative or unofficial press have in Cuba? Could the socialist state use this as an instrument of social scrutiny?

You ask me about the future of the alternative press and I tell you that the future of the official press is more nebulous. Of course, the state should use the alternative press. There are means, I will not generalize either, where quality journalism is carried out, investigative, and where relevant and sharp ideas about Cuba are conceived. A review of the debates in their forums, or the opinions they generate, convinces of the latent civic reserves, of the depth of certain proposals. An evident example was taken during the consultation of the draft constitution, from that stage I treasure the invaluable analyzes of many colleagues: jurists, historians, economists, philosophers, sociologists, communicators….

In my opinion, the official media do not offer an answer to citizens’ needs, and that is dangerous because they can seek answers that move to extremes of intolerance, where truth and lies are mixed, or fanaticism. If people don’t see themselves expressed in the official media, they will look for ways to find their reflection. It is no longer possible to maintain the monopoly on information and communications, we live in an interesting time where established points of view, systems of ideas are deconstructed. If this controversy is not fully entered, assumed not as injury but as reasoning, credibility and social roots will be lost; I think too much of both has already been lost. But the orthodox thesis of unanimity has become its Achilles’ heel, note that the campaign that the ideological apparatus makes to vilify alternative media is so crude that it discredits them. They have embarked in fight, with vile weapons, against “a common enemy” that exists only in their twisted dreams, and they have created their own Nemesis, of opposite ideological sign, but as given to sectarianism and unanimity as they are. And so harmful.

After the release of your successful book En tiempos de blogosfera, are there new titles in the horizon?

En tiempos de blogosfera it had a small print run, only five hundred copies that were sold practically the day of the presentation; however, I think it is an important text because of the precedent it could set, will it really set it? As far as I know, it is the first issue published by a publishing house of the Cuban Book Institute that compiles articles originally posted in an alternative blog. Texts have been published about other blogs but they are part of the official media sphere.

La Joven Cuba, which emerged a decade ago, is an alternative blog related to socialism, but advocates for momentous changes and from it makes a deep criticism of our reality. So the appearance of the book, despite the pathetic attempt at censorship that it must have endured, is also a sign of plurality, respect for ideas and the difference that should become something natural between us and not an exception. I am really satisfied with the reception it has had.

It seems strange to me when they define me as a blogger because, perhaps because of the generation to which I belong, it is a term that I don’t attribute to myself. I did not create the blog; I don’t even decide what is published in it. I thank the editors, currently only Harold Cárdenas remains, for guaranteeing me a space to offer my opinions, understood only as the points of view of an intellectual and citizen. It is a very comforting exercise of freedom of expression that has made me rediscover that political dimension that I admired so much when studying the intellectuals of the republic.

I have almost ready another book of essays, it is my favorite genre because of the freedom it allows, it is entitled La Historia, el arte y el tiempo. I’m also giving the form of a book to the master’s thesis of a beloved student, Liset Hevia, who died very young two years ago and left this important research on the evolution of artistic and literary criticism in the daily Noticias de Hoy, the official body of the Cuban communists since 1938. It is a subject that has been dealt with very little but is very adequate to understand attitudes that are still in force in the ideological and cultural sphere.

Are you optimistic about Cuba’s future?

Yes and no. The first I give as a historian, as someone who understands historical times and the evolution of processes. In this sense, I am convinced that the exhaustion of the bureaucratic model of socialism, which for me is definitive and not reformable, will necessarily lead to a profound change, which should include not only the economic dimension as has been vainly claimed, but also the political dimension that allows control from below, and make the already unpostponable process of transformations advance. Throughout our history, Cubans have been consistent, sometimes with delay but always with determination, with the principle of doing everything for the Homeland, for an island independent of any nation. And I have complete confidence that this future of much-needed transformations will be made while maintaining that guideline.

The second is that of the citizen, worker, woman and mother, who for decades has waited for the promise of a better future to be realized. She chronologically judges time and waits without emigrating, working in budgeted state institutions. She is the person who has seen family and friends leave, the children of friends who are now alone, and thinks of her daughters and the urgency of young people who need change and who don’t see their country offering it to them. She is the one that is disturbed by the lack of sensitivity of those who direct us to the needs of the majority and by their recurrence in failed strategies.

My dismay grows even more when I see the inadequate response given to try to control the relationship between citizens and the government, at a time when social networks and alternative media break with the customary verticality of communications and messages. And I am very concerned that this intolerance could become a real conflict.