Antonio Pacheco –as well as Omar Linares, Germán and Víctor Mesa–is part of a highly exclusive patrimony. I don’t think we are going to question the legacy of other illustrious Cuban sports figures contemporary with these baseball players. Sotomayor and Luis had something Pacheco and Linares lacked: the opportunity to compete against the toughest rivals. That places them in a context and that context obviously favored their transcendence. Let’s rephrase that: that context means transcendence. It assured them to be remembered and appreciated by European or Japanesepeople. On the other hand, let’s say it in the national dialect, each day it will be harder to keep alive the work by exceptional sluggers and pitchers who were not able to display their exceptionality in the toughest scenarios as they could have, and that results in two evil handicaps.

One: by the time we want to clear away doubts on the quality of our idols, we cannot say: “they were up to par with Frank Thomas or Bonds”, but instead “they could have been up to par with Frank Thomas or Bonds”. That undesirable speculative tone cost a lot to sports. Two: the fact that our idols have not dealt with foreign idols just as powerful, inevitably casts upon them doubts on how exceptional they actually were.

Of course, this nostalgic and grandiloquent thesis takes for granted the fact that,except for a few specific and rabid patriots I think no one would dare to refute, as usual that at some point it may be considered normal,tens of baseball players from the present and mainly from the future will end up at the Great Leagues. I won’t make any comments on if I find it fair or unfair. It does seem a natural flow. There are millions of dollars. There are competions by tons. I mean, there are material and spiritual achievements, and no commitments;regardless who you are committed to, it endures the ravages by similar forces. Perhaps we have to make some mild readjustments in our concept of nation, open a few scape valves, so that it can breathe better, so that the concept becomes an airy room rather than Raskólnikov’s lugubrious attic.

I remember that in October, 2013 , I visited Bayamo. I had never been there and I recall it was change and the Cuban identity, that thin and beautiful line, hit me so hard that my only concern was not to get out of that city turned into a politician, someone who turns changes into a habit. I remember during the evenings I used to review a small notebook with poems by Casal in my room and I used to listen to a selection of Lecuona’s pieces, mostly En tres por cuatro and Danza Lucumi, over and over again, and sometimes before going to bed (my friend won’t let me lie, because this is something I frequently do), I rehearsed swinging in the air, as if I were a fourth batter though I’m rather a ball hitter.

During the day, I mostly toured the historic area, its narrow streets, that area no bigger than two square kilometers where it all started, the Big Bang of the nation. There was a specific block, I’m not sure if it’s still there, with the house of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and, in front, Tomas Estrada Palma’s. I remember in view of such revelation I thought: Cuba was once so small it was a matter dealt with between neighbors; all the characters of the story had been distributed in a few meters. On one side of the street the illustrious patriot and on the otherthe man who sold our independence. The house of the man that started the Independence War was a few steps from the man that, 30 years later, ended it.

I explain all this so that people can understand I was free from cynicism back them. In fact, I was absorbed with and distracted by the events that gave way to my return to October, 2013, something that, by the way, also happened in Bayamo. On Sunday 20, Telerebelde was broadcasting one of the games of the World Series between the Tigers from Detroit and the Red Sox from Boston, and Jose Iglesias, the Cuban short stop stepped in the ninth inning. All of the sudden we were all in tenterhooks.

Everyone. For some reason the broadcast was not putto an end. His appearance in front of the cameras was brief, barely for an inning, but he was there. I remember I cover my face with the hands in astonishment and I recall I thought that in Havana such event would be the talk of the townfor the forthcoming days and many of us would see it as a step forward. I also recall I made myself a question, free from any resentment. A question that if I hadn’t been in Bayamo I would have hardly been able to make myself with such clarity, ease, and also with so much sadness: what’s our concept of nation?What are the goods we deal under that name so that something as simple as the appearance in Telerebelde of a Cuban baseball player in the Great Leagues would mean so much? What’s our interpretation of Cespedes’ actions? What was the real state –not the economic, not the political, not the social, but the harmonic state– of a country that saw in the figure of Jose Iglesias a sign of change?

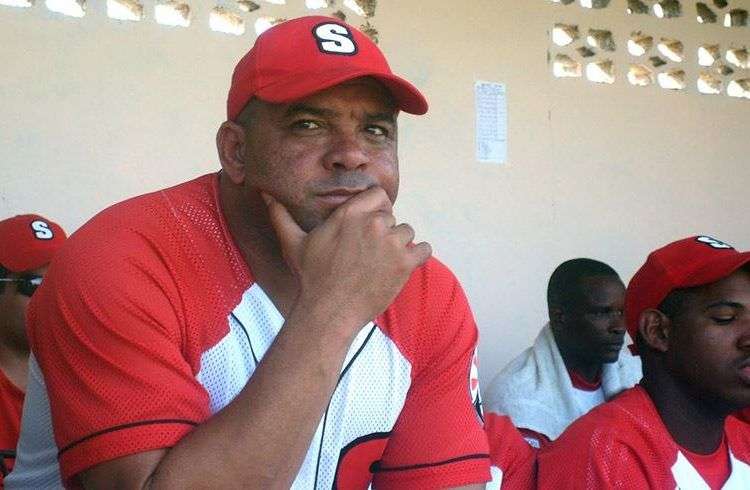

Nine months after, Antonio Pacheco – nothing more and nothing less than Antonia Pacheco– decided to migrate to the United States, and then we found out we are not as immune as we thought. His decision brought about an uncomfortable mixture of perplexity with physical uneasiness. Not because he owed us anything, not because Pacheco didn’t have the right to go where he it pleases him –even now that he cannot play in any League–, but because the idols and pieces of our memory we never thought would leave, at least not quicker than us, were actually leaving the island.

The news shocked me, but not my father who lives in Miami. I can understand it because I know what my father was and has been: there is nothing more shocking and heartbreaking for him than having to leave for Miami. If tomorrow Juan Torena ends up in Kendall, it won’t be a surprise for my father in comparison with the fact that he is already there.

It is interesting. We are not surprised that an active baseball player migrates, but it certainly is a surprise in the case of a former Cuban sports glory. Just when we were starting to get used to the idea of sacrificing the present, we must learn to let go of the past. Perhaps all this, our sadness, our astonishment, our uncertainty, are nothing but the result of a mistake. Honest expressions harvested in the wrong field: that of the nation as a physical redoubt. I would rather suggest we may start making amendments from the roots.

The fact that we think that with Pacheco living abroad we lose something doesn’t mean we have actually lost it. The question is less selfish: why the best second base player of the National Series had to migrate to the United States, when what he represents only makes sense in Cuba? What led him to leave his country, considering he didn’t left when he was at the peak of his career? Ironically, no one will ever be able to claim he did it for money. It is rather a salvation act than the search for wealth.

He and Vera are absolute referents of my childhood. I close my eyes and I still see him running. I was 12 or 13 years old when he retired and about 10 when he hit a homerun off Lazo. If no one confirms it, I could think that incredibly cinematographic homerun was never true. My regards then to Antonio Pacheco, captain of Cuba; my regards to my father, captain of Cuba; warm regards to my close friends, captains of Cuba. Don’t get distracted or excited. It seems we are going to extrainnings.