Cuba was on the verge of not being part of the history of the World Baseball Classics, at least that indicated what happened in the inaugural edition of the contest. On December 18, 2005, two and a half months before the opening of the event, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) denied the island a license to compete. If the country obtained economic benefits with their participation, the blockade would be violated.

The roads seemed closed. However, after a series of complaints and negotiations, finally, on January 20, 2006, Cuba was granted permission to participate in the tournament, where several of the main stars of the sport of balls and strikes would meet for the first time under the flag of their respective nations.

“Cuba is back in the game,” said the headline of an article in the Los Angeles Times in those days. It was celebrating the reversal of a decision that affected genuine competition over political issues. The news item itself included statements by Democrat José Serrano, a member of the United States House of Representatives, who considered that sportsmanship could transcend political disputes.

“Allowing Cuba to play in this baseball tournament was the right decision, both for the fans and for international relations,” Serrano said then.

However, said authorization did not completely put a stop to political debates. Molly Millerwise, then spokesperson for the Treasury Department, assured that the license granted did not limit “the legal scope or the spirit of the sanctions against Cuba,” since she did not contemplate that any financing would reach “the hands of the regime” of Fidel Castro.

This was a very clear message after the Havana government, in order to make the team’s participation in the Classic viable, expressed its intention to donate the proceeds from said event to the victims of Hurricane Katrina, which had devastated the central-southern area of the United States in August 2005.

“Cuba is not licensed to receive any income from participation in the World Baseball Classic, so it will not have any income to donate to the victims of Katrina,” said Eric Watnik, spokesman for the State Department’s Office of Western Hemisphere Affairs.

This line was later reiterated by Patrick Courtney, vice president of Public Relations for Major League Baseball (MLB). Courtney said, during the negotiations with Havana about the participation of the Cuban team in the Classic, that it was “clear as day” that Cuba would not receive any part of the profits. Not even for charity.

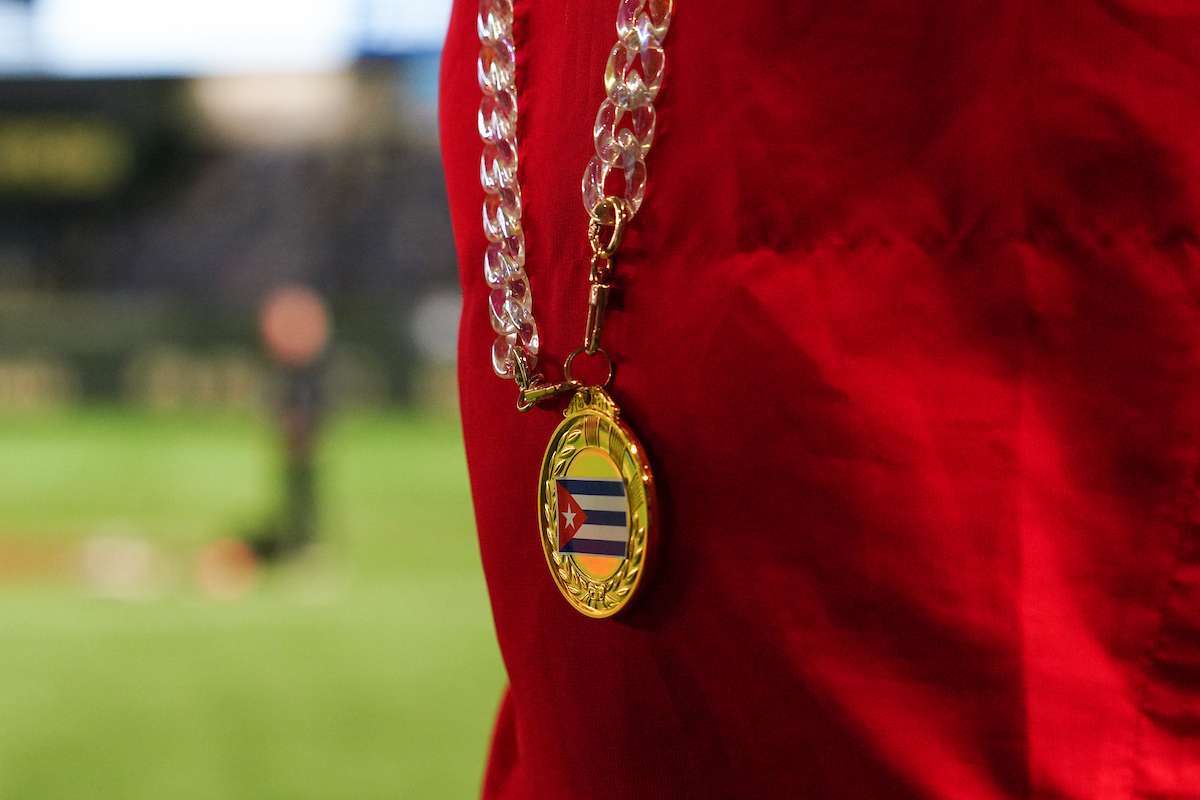

In the midst of all these statements, the Cuban squad played in the first World Classic and finished in second place after losing to Japan in the dispute for the crown. Before, they had impressed the world after getting past the two initial rounds and the semifinal, defeating teams packed with professionals such as Venezuela, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

According to the regulations established by the organizers, this performance would allow it to take 7% of the economic benefits of the event, but that never happened. In the end, the Cuban Baseball Federation did not receive any award, so the donation to the victims of Katrina was not consummated either.

On the other hand, the players of the team did receive awards, but by the Cuban State itself, from which they received an amount close to 10,000 dollars in total, three players from that team, who asked to remain anonymous, confirmed to OnCuba.

What happened to the money that was due to Cuba for its performance in the first Classic is still unknown. In 2006, MLB officials noted that “if there were unallocated net proceeds, they would consider a donation to a charitable or humanitarian cause to be determined.”

However, no further information was disclosed about the destination of what Cuba earned for its performance on the field. None of the organizations or funds to which the money was supposed to be delivered have reported such donations.

In 2009 and 2013, Cuban baseball players also did not earn a penny for their participation in the editions of the Classic, despite the fact that they earned a million dollars in each of the events for advancing to the second round and finishing at the top of their qualifying group. According to the testimony of some players included in those teams, it was explained to them that this money would be frozen in the United States due to the blockade restrictions.

In 2017, although Barack Obama was no longer president of the United States, his policy changes towards Cuba had not yet been reversed. At that time, an agreement was being negotiated from the island to normalize the flow of players to the MLB, which made it possible to find ways for the Cuban players to get paid for their performance in the fourth Classic.

In said contest, Cuba theoretically earned around 700,000 dollars for advancing to the second round behind Japan in group B. At least part of that money was actually collected through an account set up by the World Baseball Softball Confederation to receive the money from MLB, according to the anonymous account of two members of the national team in 2017.

These players claim that they earned about $11,000 each shortly after the tournament, not counting the pocket money ($100 a day) that the organizers gave them (as well as the rest of the teams) during the competition in Tokyo.

On this matter, it is unknown if the Classic only deposited the players’ money or if it also paid its part to the Cuban Federation, which legally could not receive direct economic remuneration, since it violates the blockade regulations. In this regard, the Cuban authorities have never made an official statement.

Six years later, relations between Cuba and the United States have reached a point of absolute tension. Just in the field of baseball, the Donald Trump administration canceled in 2019 the agreement signed months before between MLB and the Cuban Federation in order to normalize the flow of Cuban players to U.S. professional circuits without this representing breaking ties with the national sports movement. In mid-2021, the Caribbean participation in the Pre-Olympic of the Americas in Florida was endangered due to difficulties in obtaining a visa.

On the other hand, in December of last year, Cuba was required to obtain a special license to summon professional baseball players residing in the United States for the 5th World Classic, which was considered by the island’s authorities as “discriminatory treatment.” Previously, the island had requested another special permit just to participate in the competition.

Under these conditions, one would assume that there would be no changes regarding the distribution of profits for participating and Cuba’s sports results. In fact, a Treasury Department spokesperson told The New York Times last week that “the Cuban Federation and its players cannot receive any income or prize money from the WBC. (Classic) under the licences.”

However, Juan Reinaldo Pérez Pardo, national commissioner and president of the Cuban Federation, told Martí Noticias in Miami, before the semifinal duel against the United States, that MLB requested a license from OFAC for the island to compete with the same rights as others.

“There has been a lot of speculation about that, but the negotiations that have been carried out from the beginning and the permits that have been issued establish that all Cuban athletes receive the same benefits as the rest of the baseball players receive,” said Pérez Pardo, who also gave hints about a possible payment to the Federation.

“It is something that has been talked about. It is not money that the Federation should receive directly because of incomprehensible things. In the end, the money will be placed in a place (an account) defined by MLB,” added the federation official.

Cuba accumulated a total prize of 1.5 million dollars in the 5th World Classic: 300,000 for participating, 400,000 for advancing to the second round, an additional 300,000 for winning in their group and 500,000 for reaching the semifinal.

Half of that money goes to the players, who would receive around $26,000 each. This was reported by independent journalist Francys Romero a few hours after the end of the Classic. The reporter himself indicated that the payment to the Cubans should be made in the coming weeks, although the ways and methods to transfer the money are unknown, especially to those players who reside on the island.

Contrary to what happened on previous occasions, Cuba and its sports authorities should report with the greatest possible transparency on each of the steps of this process in order to avoid speculation, suspicions, and attacks.

Follow OnCuba’s coverage here: