Alexis Valdés, the well-known Cuban actor and comedian, began performing the monologue “Defending the Caveman” at the Trail Theater in Miami on Sept. 6, 2013. It is a piece written in 1991 by U.S. actor Rob Becker, who won the Laurence Olivier Award for best entertainment that same year.

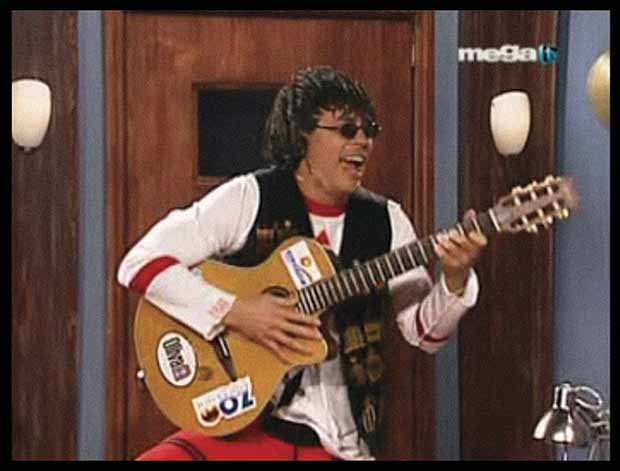

In January of 2013, after five years of producing, directing and hosting the Mega TV show “Esta Noche Tu Night,” Valdés left the program. The comedy show sparked and still sparks great expectations, winning Latino television’s largest audience.

When “Defending the Caveman”—which broke a record for longest-running Broadway show—premiered at the Trail, it was expected to last only through the month of September, with Friday-through-Sunday performances. However, it was so well-received that it remained for many months longer.

It is the first time that a Cuban artist has performed the piece, and Valdés, with his perseverance, dedication, honesty and capacity for hard work, has been handsomely rewarded with the acclaim of public and critics alike.

What was it about “Defending the Caveman” that made you interested in performing it?

I liked what the text was proposing, its intentions of uniting and not dividing—which is something that always moves me—and its universal success. It is a magical piece that tries to explain, in a fun and intelligent way, the differences and disagreements between men and women. It may be the most talked-about recent theater hit in Miami, and I’m grateful for that. Doing “Defending the Caveman” has made me feel like an artist and an actor again.

This monologue has many different versions; they say more than eight million people in 45 countries have seen it, in 15 languages. What did you contribute to the script?

I gave it my “Cuban-Miami-esque” adaptation; I put in my jokes, ideas, and experiences. I worked on the text for a couple of months. The president of the Icelandic company that owns the rights told me: “For the first 10 minutes, nobody laughs, but don’t worry, because that’s how the piece is.” But I can’t go for 10 minutes without anybody laughing; it depresses me. So I adapted the first 10 minutes.

What has been the reaction from the critics and public?

There was one review that seemed to have been paid for by me, ha ha…it says that Rob Becker wrote the piece for me without know it. That’s a great compliment, and I’m grateful to the journalist. But the public has done it all, with their laughter and applause, and with that word of mouth that filled up the theater every week. I had never done a show where I got a standing ovation at the end of the night every night—Wow!

What do you think were the keys to success for your program Esta Noche Tu Night?

It was a program that took a fresh approach to humor; a daring and refreshing proposal in the Miami context; above all, we were honest and not facile. What has always been successful? Doing comedy with Cuban politics? Well, let’s not do that.

In your performances for Esta Noche Tu Night, you frequently used a sort of “humoristic impartiality”; could you conceptualize this from the standpoint of humor?

I don’t know what humoristic impartiality means. I suppose it refers to the fact that we were “not for or against anybody.” I think that a comedian—someone who questions society—should not have any commitments to political tendencies. It would not be honest to use humor for political opportunism, but it would be to question politicians, because if comedians don’t do it, who will? [José] Martí used to say: “Humor is a whip with bells on the tip.”

Do you know that your program was followed in Cuba, and that even though it is off the air, people still watch it?

That makes me happy. It is my country, my people, and it was a gift. We didn’t do it with that in mind. It just happened. I was acting for the market where I was, Miami. One day they told us, “The show is a super-hit in Cuba,” and we said to ourselves, “Well, let’s take that into account,” and so we started doing things while keeping in mind the people on the island, too.

A lot of rumors are circulating, on both sides of the Strait, about whether or not you will return to TV. Would you like to announce something to that effect?

We’ve been working on that for a long time, ha ha. I’ve been fighting for more than a year on certain working and contract conditions that will make me a little happier. People think it’s just about money. If all I cared about was money I would be a banker, not a comedian.

Who are the comedians that you most revere, and who taught you the most?

My references were always Chaplin, perhaps the greatest in the world; Cantinflas, surely the greatest in the Spanish language; Leopoldo Fernández,1 the most successful Cuban comedian of his time, and who had a major impact on Latin American radio. Subsequently I met Gila,2 in Spain, and I learned a lot by watching him, in fact, I worked with him. I also very much admire Peter Sellers, the actor from The Pink Panther, Being There, and other great things. Guillermo Álvarez Guedes influenced me with that unique way he has of telling a joke and saying a word—supposedly rude—and always being elegant. That is mastery, too.

In a certain way I was influenced by my compatriots Alejandro García, Virulo, in that way he has of doing comedy with song; Carlos Ruíz de la Tejera, in being an artist as well as a comedian; and of course my father, Leonel Valdés, my involuntary teacher. I learned from him that more than anything else, a comedian is an actor.

What do you remember most about your relationship with the public in Cuba?

Many things. Imagine, it was my first public, and it gave me a lot of joy—not a lot, an immense amount. It was a love story: they gave me laughter and I worked hard to do better, to learn, and to constantly surprise them. Based on that type of collaboration, you can be free to create, take risks, and even to be wrong. But when they love you, they forgive you and make up excuses for you; they give you one more opportunity, and then another…. The public in Cuba pampered me. Some of the shows that I did in theaters and nightclubs were so tremendous in terms of the laughter that I think—and I’m aware that memories are idealistic—that I felt a magic, a state of grace, that I never felt again.

Would you like to perform on the island again?

Cuba is my homeland. A ton of people there have the same roots as I do, went through the same childhood, which is something essential. When comedians talk about their childhood with the public of their homeland, that shared childhood with its tender and miserable moments….that is something you just can’t beat.