Last June 4, according to his birth certificate, Faustino Oramas Osorio, “El Guayabero,” one of the legends of Cuban music, would have been 107 years old. While I write this I have my doubts because, although it is known that the trova singer died in March 2007 at the age of 96, in his native Holguín many claimed that he lived to be more than a century old.

His life and his songs were in themselves a mixture of fables and anecdotes. In fact, his stage name came after he escaped from a town in eastern Cuba called Guayabero (now Mella municipality, in Santiago de Cuba). And all because of his Don Juan airs. He had fallen in love with the wife of the corporal of the rural guard.

After the flight he wrote: “Trigueñita del alma no me niegues tu amor, / trigueñita del alma dame tu corazón, / nunca pienses que un día/ pueda yo olvidarte. / ¡En Guayabero, mamá, me quieren dar!/ ¡En Guayabero, mamá, me quieren dar!”

His sense of humor led him to use picaresque language in the texts of his songs. So much so that the bard was also baptized as “The king of double meaning.” Among his refrains, the most famous one may be the one that goes like this: “A mí me gusta que baile Marieta…”. “Marieta a mí me pidió / tres pesos con disimulo. / Y me dijo que me pagaba /con el tiempo y… sin apuros.”

It was that imprint that inspired Cuban filmmaker Octavio Cortázar to film in 1984 the documentary ¡En Guayabero, Mamá… (Me quieren dar…). In the documentary, filmed almost entirely in Holguin, we can enjoy the trova singer in the most dissimilar facets. It is accompanied by the theoretical reflections of musicologists Radamés Giro and Helio Orovio. This film is a jewel that not only gives an account of El Guayabero’s musical originality and character itself, but also shows that Don Faustino even broke with that phrase of “no one is a prophet in their land.”

El Guayabero is also recognized by his colleagues. Singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés defined him as “a popular genius whose very special characteristics within Cuban popular music can’t be classified in a certain tendency.”

On the other hand, musicologist María Teresa Linares has written that “Faustino Oramas represents a phase of the son, perhaps initial, perhaps primary; but which he maintains with a lot of strength, with a lot of quality. Faustino uses the forms of the son that were used in the past, the montunos, on which quatrains and décimas were improvised.”

That is why trova singer Pedro Luis Ferrer, an admirer and friend of El Guayabero, author of memorable sones and guarachas and creator of the changüisa genre, recently told me that Faustino “is much more than the King of double meaning. He is the great exponent of the montuno in Cuba.”

And the latter is concatenated with a reflection I read from tres-player Pancho Amat: “The Guayabero is a popular tres player of tumbaos, which uses a very repetitive rhythmic melodic design, in whose most basic cell lies the Cuban flavor. I have studied it carefully, because sometimes there are closures in the orchestra that allow me to start with a tumbao that everybody likes, I take away or add something else to it, but I am inspired by Faustino Oramas.”

Today his work can be found on different digital platforms. Some record labels, especially Egrem, insisted on including him in their catalogs when he was almost 80. He recorded few albums, among which a compilation titled El Guayabero and El tren de la vida, his last production, stand out. It also remains recorded on more than a dozen albums by different artists. It is perhaps the legendary and most important production, Buena Vista Social Club, which features a theme of his, “Ay, candela,” performed by Ibrahim Ferrer.

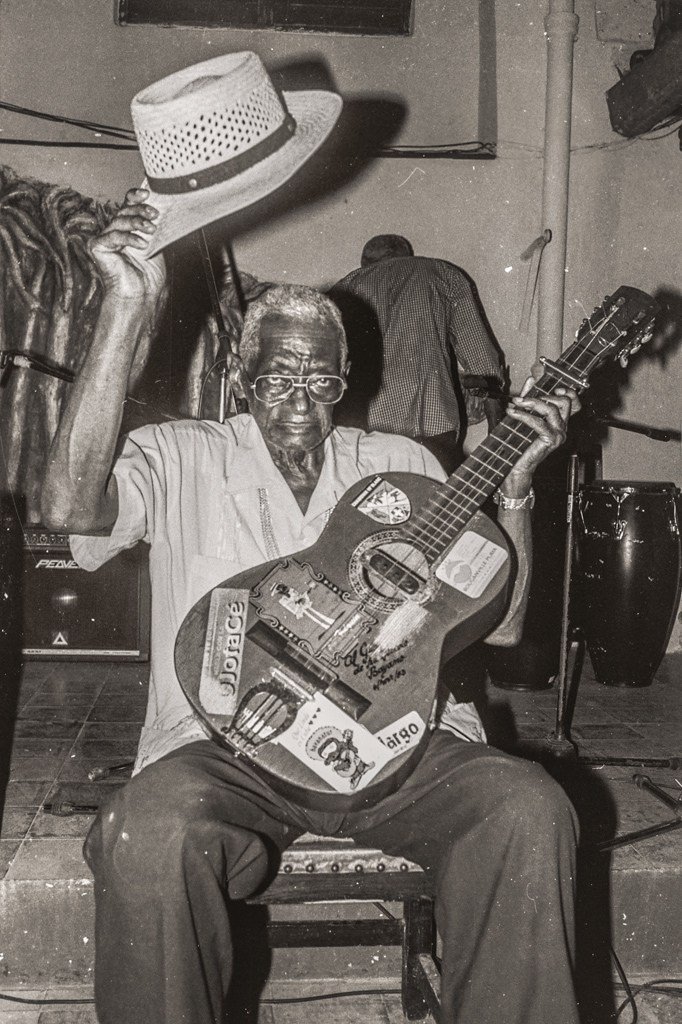

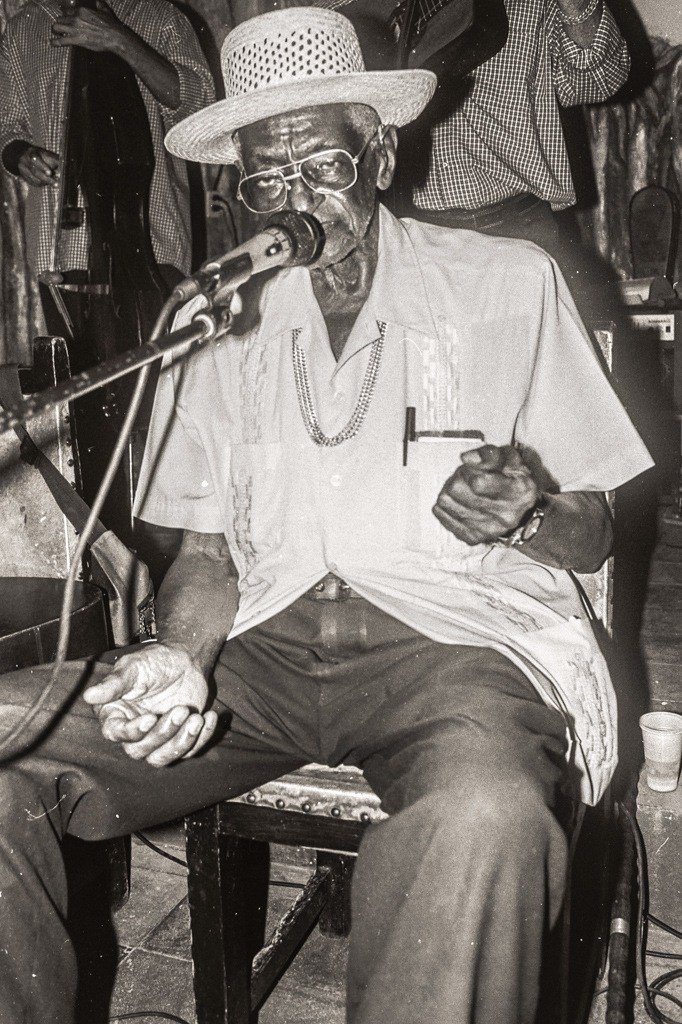

A few months before he died I was able to photograph him. Once with black and white film, in full concert in the Casa de la Trova in Holguin, which since 2002 bears his name. The other a few months later, in the privacy of his home. He died when he had just turned 96. The weight of his almost 100 years was noticeable, but he maintained his appearance of a trova musician. So much so that upon noticing the camera, he did not allow me to press the shutter until he put on his straw hat and was stringing his old guitar from a thousand battles.