Sugar, Cigars and Revolution, the Making of Cuban New York (New York University Press, 2018) is the latest work of Professor Lisandro Pérez, founder of the Cuban Research Institute of Florida International University and currently a professor of Latin American and Latina/o Studies at John Jay College of the City University of New York. This year he received an Honorary Mention in the Casa de las Américas Award in the category of Studies on Latinos in the United States.

The author does not deny that his work is an elitist book because instead of emphasizing the popular, it concentrates on demonstrating that it was the aristocracy that settled, opened paths and consolidated the Cubans in New York.

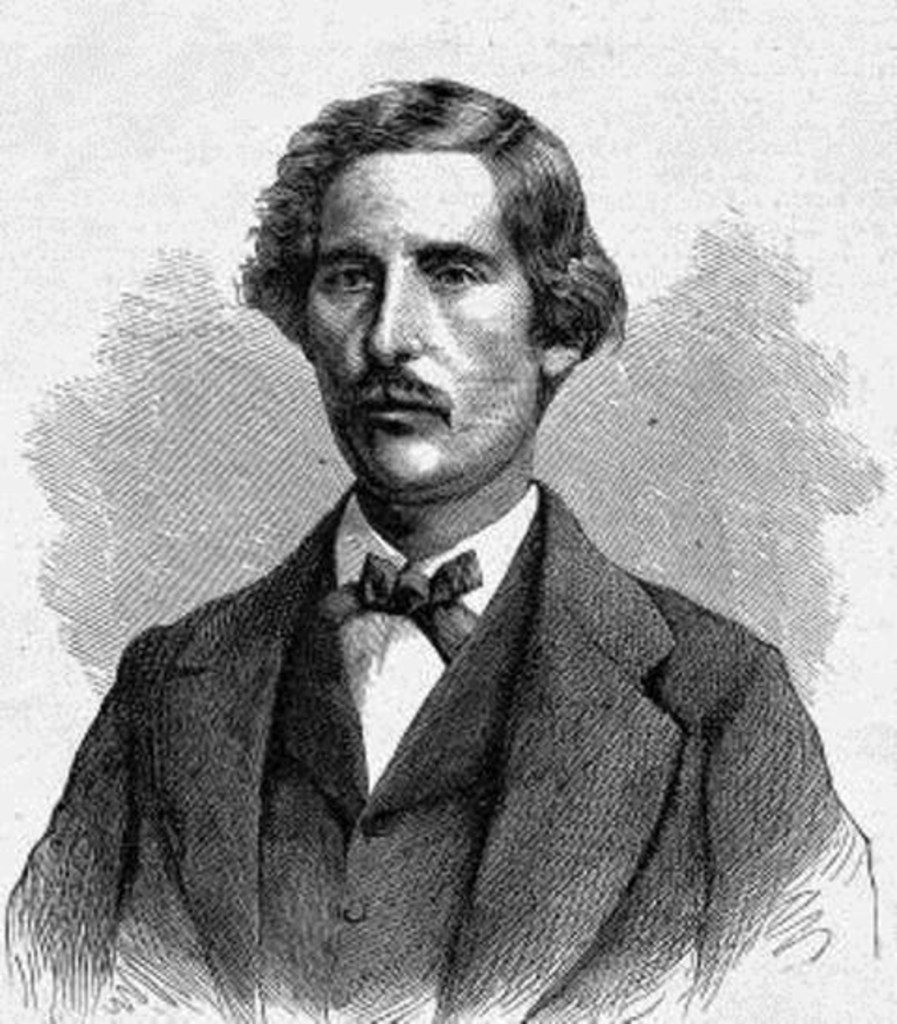

Félix Varela was the first, José Martí is perhaps the best known Cuban in what was beginning to be the city of high-rise buildings. Antonio Maceo and Máximo Gómez also passed through there. But those who really left a mark were the families of the sugar aristocracy. The Aldamas, the Moras, the Alfonsos, the Acostas, the Jovás, whose imprint, despite the ruin of some, lasted far beyond sugar imports and industrial development.

It is an easy to read book, even if it has a compact and dense appearance. A great deal is learned. It reveals an unknown universe. But fascinating. One afternoon we sat down to talk with Lisandro Pérez, who had just turned 70, at his home in a quiet Miami neighborhood.

I found many things in the book about which I had no idea. Cuba and New York go way beyond Martí. People are convinced that Martí is the great Cuban symbol in New York, but he isn’t.

When I started this project, people asked me what I was working on and told them on Cuba and the United States around the 18th and 19th centuries. But really the story is that when Martí got to New York there was already a path, it can be said, a road already used by Cubans who went there. In fact, he is not the first Cuban, it was Félix Varela―I begin with the story of Varela, who arrived in 1823―but that story begins much earlier with commercial ties such as sugar and with the sugar revolution in Cuba at the end of the 18th century.

That sugar that was increasingly being produced in Cuba was sold in New York. It was not a product from Spain. Then the Cubans opened bank accounts in New York and built a bridge that started livening up that place. When Varela left Cuba, he stayed in New York. He considered it the closest place to Havana and, of course, every day there was a ship that sailed from there.

There comes a time when commercial communications with New York were greater than with Florida…

Florida was nothing at that time. There were some cigar factories in Key West, but they were very small. Tampa didn’t open until 1886. The cigar industry didn’t open until then and was introduced by cigar workers who were in New York, during the Ten Years War. They settled in Ybor City, but New York continued being the origin of all this. Of course, in the 1890s Ybor City surpassed New York.

The immigration that goes to New York beyond the sugar industry is an industrial immigration, but it also has another facet. It is an immigration that does not reject culture. Deep down do these families form part of the city’s cultural family?

Partly because they were the elite. One of the things that the book is different from some of those that have been written about the Latino presence in New York is that they emphasize the Afro and working population in New York, partly because they are topics of interest to Afro-Latinos in New York. But mine really isn’t like that because what I discover is that these migrations are initiated by the elites. The starting point of that Cuban immigration is the sugar business. And those who came and went and settled here are Havana elites. Cubans from Havana.

In that sense, there are certain parallels between that immigration and contemporary Cuban immigration at the triumph of the Revolution. The first in greater proportion are the elites, they are committed to the island’s political situation and they lobby and carry out a series of activities to change the regime on the island and there are documents from that time that reveal there is a whole lobbying by the elite to buy Cuba, so that the United States becomes interested in everything about Cuba, and it is even promoted by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes himself. When the war of 1868 breaks out, Céspedes appoints a whole delegation of landowners to represent his government in Washington in order to achieve a favorable policy for regime change in Cuba. There are those parallels. It is an elite that set up a lobby at the highest U.S. government levels.

These people obviously wanted to separate from Spain, but did they also want to be annexed by the United States?

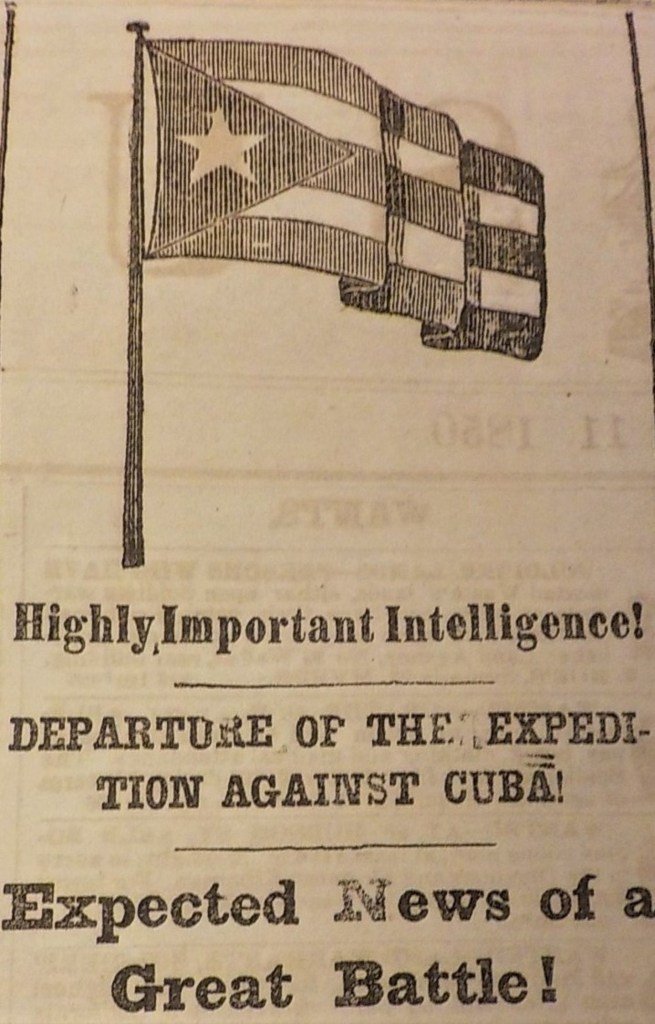

That changed over time. When it started in 1840 and a bit, it was an annexationist movement. That is, the Cubans who were prominently there in New York were annexationists. The idea was that Cuba abandon the oppressive colonial regime and enter the modern era as a progressive country like the United States, but in part it was to extend slavery. And they saw that Spain was flagging in the face of British pressure. They thought the model to follow was that of the United States, eliminating trafficking but maintaining slavery. The landowners were already worrying because Cuba was turning black with all the slaves. They favored that model, I repeat: eliminate trafficking, but maintain slavery. And for them the best model was that of the United States.

It’s when the Cuban flag is born. It is born with an annexationist movement and is a deeply annexationist flag. That flag was born in New York. The landowners did not want war, it destroyed the lands, and there were many conflicts within the Cuban community in New York. Many thought that these landowners that Céspedes had put in control of the movement were not doing enough to take the war to Cuba.

Why was the United States more important than Spain for the landowners? Weren’t the Spaniards interested in sugar?

New York was the first sugar refining center in the United States. I’m talking about the end of the 17th century, the 1600s. By this time there were 14 or 15 sugar refineries in New York. So the idea was to buy sugar from Cuba, a sort of brown sugar nougats that were refined and were bought like that from the landowners. Cuba had no refining capacity. These New York offices, called county houses, received that sugar at the port, it was consigned to them, they collected their commission and then there were the bank accounts because these landowners did not want to have their money in Cuba.

However, it was much more than the sale of sugar. These people depended on and trusted the American Moises Taylor sugar corrective company. For example, Tomás Terry, the Cienfuegos landowner, asked Moises Taylor to please buy with money from his account a ring and a necklace for his daughter who was to be married. When Tomás Terry sent his children to New York, he placed them under the guardianship of Moises Taylor. They fully trusted that house. Moises Taylor was in charge of taking care of these children, of buying jewelry, of the orders they made.

When the landowners were forced to leave the island in 1868, all that Cuban sugar aristocracy of Havana, where do they go? To New York because that’s where all their money was. They had also been there many times. Already by 1850 and a bit, Cubans are known in New York as a wealthy group, with that air of European aristocracy. As of 1870 they were the largest group of Latin American origin in New York, beyond the Spaniards and all those from the Caribbean. We also have the traffic of ships. Between 1830 and 1850 the number of ships that arrived directly from the port of Havana to New York was way superior to those that came from all the ports of Latin America and Spain. That was trade. It was there.

When and how does trade begin to decline? When the aristocracy left the island or when the war of independence ended?

That traffic continued a little during the Ten Years War because there were some landowners who did not have to leave Cuba and continued selling the sugar and the sugar arrived. But it was also because of the problem of the war, which greatly affected the sugar industry. The Spanish government seized the assets of any person who left the country. Another parallel we were speaking about. Even after the war, with the Zanjón Pact, the Spaniards declared an amnesty, that is, they returned but nothing was said again about the properties.

Historians documented thousands of Cubans whose properties were confiscated by the Spanish government. First it was an act of war, but then came corruption. The Moras, a very important family in New York, spent years in court in a lawsuit against the Spanish government for their property. At the same time, sugar had been declining, beet made its appearance, and that class that risked everything with the 1868 war of independence could have said: “we are loyal to Spain” and no problem. But they took the risk and at the end of that war they were virtually economically bankrupt.

And does the United States enter the Cuban sugar industry after independence?

With independence, after 1899. Through the island’s eastern province, because the sugar industry we are talking about in the 19th century was in the west, around Havana and Matanzas. What there was in that eastern region was countryside. Then, at the beginning of the 20th century, J. P. Morgan and others arrived, and they established large sugar factories with a majority of Haitian workers.

Why didn’t these families, the Aldamas and the Moras, return and file a complaint against the independent government?

So many years had gone by. That ended in 1868. Part of what happened in 1898 and 1899 is that the Americans were not willing to change the property regimen. As in the rest of Spanish America, they said: “We beat the Spaniards, they left and we took over their property.” But the only ones who had to leave Cuba when Spain cedes Cuba to the United States were those in the army. The Spaniards stayed and stayed with their businesses. The Americans did not change the ownership regimen. Moreover, after the War, with the American occupation, the people on the island started saying: “Now we are Spaniards, we are Cubans.” From the Spaniard who had his grocery shop in the town to people like the landowners, they retained their property. But many also stayed here. In the end the Moras won the lawsuit in 1902 or 1903 for Spain to compensate them.

What happened to those families, did they stay, integrate, disappear into American society?

Some stayed in the United States; others returned. But those who returned were not able to recover their properties. The Madans, Aldamas, Alfonsos, who were all a single family because they married among each other, at first actually didn’t have much money. Aldama Sr. arrived in Cuba in 1830 because the country’s wealth was growing. That Cuban elite of Havana is really quite close to a migration process in Spain. They seek, to some extent, fresh money because money can be made from the sugar industry. Not like those from the eastern region, like Céspedes, Aguilera, the Mirandas, who were there since the 17th century.

And the most important ones who remained in New York never left?

They created wealth in Cuba, but lost it during the Ten Years War. The Madans are here, the Moras…they are all buried in a cemetery in Brooklyn. Aldama is buried there with all his sons, his daughters and his sons-in-law. The Moras are there, there was a Mora who became a famous photographer in the 1920s, he took theater pictures in New York. There was a family called the Acostas, among those who stayed. The original Acosta came with the Ten Years War, married a Spanish lady of noble birth, a descendant of one of the Albas, and that family was legendary in New York. She had a sister who was a pioneer in aviation, another sister was a playwright who died in the 1960s and was supposedly one of Greta Garbo’s lovers. There is a biography about her, entitled That Furious Lesbian. The Jovás, who came from Santa Clara, went to live up the Hudson River and established a very important brick-making factory with clay from the banks of the Hudson. That is another story about the people who stayed in New York and made money, but Aldama lost almost everything.

How do you see the book?

My intention with this book was to tell this story, not extensively but at the level of families who, in effect, were the ones who made up the immigration. One of the things I can be criticized about is that it is an elitist book, I place emphasis on these families. We have the cigar makers, a more proletarian class too, but in my opinion the driving force of this immigration was this elite. The interesting thing about elites is that they leave a bigger imprint. The cigar makers were very important, but already by 1880 New York changed, it no longer had that immigration of people who have gone broke, a more proletarian immigration started arriving, and that is when Martí began his movement. And Martí learned that wealthy people are actually cautious, and that if he was going to make that move he had to start at the bottom. He wasn’t liked much among that New York elite.