The popular image of tourism in Cuba is of foreigners who arrive by air or sea to stay in hotels or private homes for rent, or as passengers on board cruise ships. The trips of Cubans residing abroad are not seen as tourism, although in many cases they are, totally or partially.

Migration and tourism are the two essential components of the mobility system. Migrations are transfers from the place of residence to live in another place, for a relatively long time. International tourists, like international migrants, cross borders but the intention is not the same: the tourists temporarily leave their principal domicile to go to live elsewhere for a relatively short time. Migrants can become tourists when they temporarily return to their countries of origin. [1]

The reasons for traveling to Cuba for these emigrants, in particular, are varied and on multiple occasions comprise visits to family and friends on the island, but there’s also nostalgia tourism, to get to know their roots, to enjoy sun and beach hotels, many times in the company of their relatives in the country. In other cases, visits are associated with resettlement processes, the purchase of properties or investments on the island, and with trade in merchandise imported from the country of residence and exported to Cuba. In all these cases they have an impact on the local economy equal to or greater than foreign tourists.

And the figures are not small: since 2010, except in the years of 2017 and 2018 of the non-Cuban American tourism boom, the second tourist “issuing market,” after Canada, has been the Cuban community abroad, with an annual growth rate of 8.2 percent.

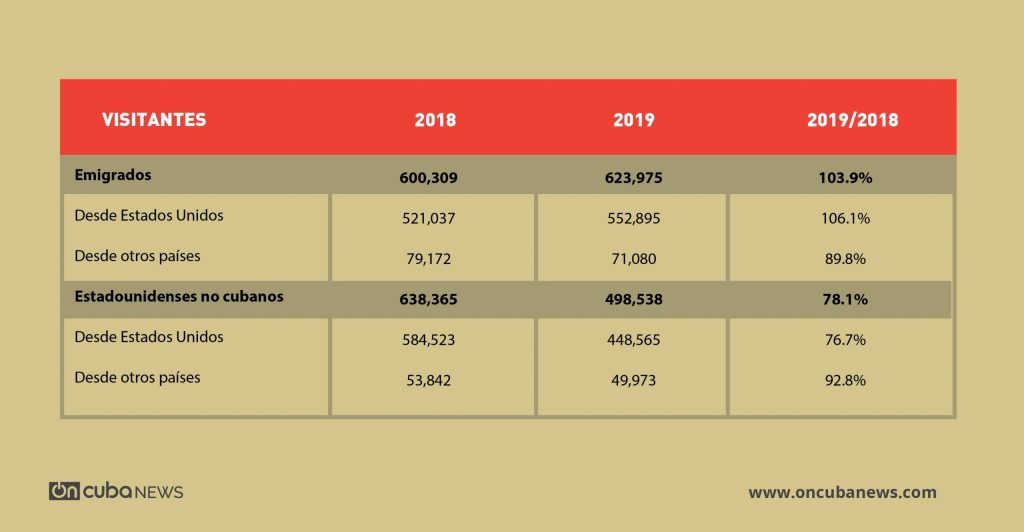

The amount of visiting emigrants for 2019 was 624,000―88.6 percent from the U.S.―an increase of 3.9 percent compared to 2018. Meanwhile, arrivals of non-Cuban Americans saw a 22 percent decrease in 2019 and Canada grew just one percent, compared to 2018. [2]

——–

*Caption

Visitors

Emigrants

From United States

From other countries

Non-Cuban Americans

From United States

From other countries

———

It was equally evident to the Trump administration that visitors of Cuban origin have resisted the travel restriction measures adopted since 2017 and propped up tourism on the island in 2019. It is not surprising that this was the target of the measure taken by the end of 2019 when he put an end to the regular U.S. flights to the airports inside the island, with the exception of Havana, effective December 10. The most affected have been Cubans residing in the U.S., which so far constituted 73 percent of the passengers on those flights.

As expected, on January 10, 2020, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. administration will also suspend charter flights from the United States to all destinations in Cuba with the exception of Havana’s José Martí International Airport and a cap will be imposed on the number of flights allowed for this destination. This affects nine Cuban airports currently receiving charter flights and will take effect next March 10.

The measure sparked an immediate condemnation by organizations that favor understanding with Cuba. The Center for Democracy in the Americas (CDA), along with Engage Cuba, the Cuba Study Group, Oxfam, Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), and Latin American Working Group, condemned the action. Emily Mendrala of CDA stated that “Today’s State Department actions force Cuban families to travel further, pay more, and take convoluted routes to see their loved ones, while also bringing us one step closer to closing the door to Cuba altogether. These senseless and mean-spirited policies are unlikely to change the Cuban government’s behavior or force a new approach to Venezuela, and, if anything, create resentment among the Cuban people. But the policies will have a practical impact—an unfortunate one. The charter companies losing money are U.S. businesses. The passengers are largely Cuban families, U.S. church groups, and academics. The Cuban communities connected to U.S. travelers by these flights are remote and poorer than those in Havana. They are the losers of today’s announcement. The strategy of sanctions and isolation didn’t work 60 years ago and it’s unlikely to work today.” [3]

At the time of these measures, five U.S. airlines maintained regular flights to Havana―they are American, Delta, Southwest, United and JetBlue Airlines―from Miami, Ft Lauderdale, Orlando and New York. In addition, eight other charter companies operated more than 70 weekly flights to Cuba: Marazul Charters, Wilson International Charters, Xael Charters, ABC Charters, Airline Brokers, C&T Charters, Gulfstream Charters and Cuba Travel Services. They all fly to Havana and other airports in Cuba from Atlanta, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Tampa, Los Angeles and New York.

The measure against regular flights to airports outside of Havana may have had some impact. In December 2019, 12.5 percent fewer passengers arrived by air from the U.S. compared to the same month in 2018, although the drop was less―8 percent―for Cuban-Americans. In any case, this decrease cannot necessarily be attributed to the suspension of flights to the provinces, since airlines and charter companies raised prices significantly, especially around holidays, motivated by the high demand. The impact of the suspension of all U.S. flights to destinations outside the capital remains to be seen.

An even more important index to measure the impact of tourism than the number of arrivals is that of tourist-days, the number of tourists by the number of days of stay. In 2018, Cubans living abroad averaged 11.2 days of stay for a total of 6,723,460 tourist-days. The average number of days of stay for non-Cuban Americans was 7.7 and for all international visitors 9 days. [4]

Tourists staying in private homes for rent average 2 and 3 times the number of days of stay than those in hotels, so their impact on the economy is much greater. Although many assume that Cubans living abroad stay in family homes and do not pay rent, we don’t know exactly how many stay in private homes for rent or in hotels. While Cuban emigrants stay longer in the country than the average of foreign tourists and tend to stay in private homes, even if they don’t pay rent, the contribution in kind and cash to relatives in Cuba, plus their own expenses during their stay constitutes an important contribution to local economies, in the state as well as the private sector.

Emigrants’ visits also influence the occupation rate of hotels by national tourism, since it is common that when Cubans living abroad invite their relatives to go to a hotel with them, the reservation is made by the national and thus recorded statistically as national tourism.

The boom in national tourism in the summer of 2019, attributed to the salary increase in the budgeted sector and to the increase in the tourist offer aimed at that market, may have an international tourism component to the extent that a part of the 469,000 Cuban residents abroad that traveled to Cuba in the first nine months of the year financed those stays. In fact, between January and September 2018 and in the same period in 2019 there was an increase of 18.4 percent in national tourist-days staying in hotels in CUC, with an average stay of 2.2 days per tourist, which suggests that they stayed many weekends. [5]

The consumption of certain non-hotel tourist services such as car rental may also be higher for visiting emigrants.

In short, the economic impact of trips to Cuba by Cubans residing abroad is significant, although difficult to quantify due to lack of data. Their resilience to the restrictive measures of the Donald Trump government, with a sustained growth in arrivals even in 2019 when the general trend was declining, attests to the strength of family and cultural ties between the nation and its emigration.

Notes:

[1] Perelló, José Luis (2008). Efecto de las migraciones internacionales sobre los flujos turísticos para Cuba y el Caribe. Thesis presented for the scientific degree of Doctor of Economic Sciences, University of Havana.

[2] ONEI, Statistical Yearbook of Cuba, 2015, 2016 Edition; 2018, 2019 Edition. MINTUR, Newsletter, December 31, 2019.

[3] Center for Democracy in the Americas info@democracyinamericas.org January 10, 2020.

[4] José Luis Perelló (2019), “El Turismo en Cuba ante el deterioro económico global. Nuevos retos, nuevas estrategias.” Excelencias, November 2019.

[5] José Luis Perelló (2019). Idem.