Again there is pain; and frustration, anger and shame accumulate and grow, yeast that is not to become nourishing bread. The dialogue that against all indications of reality I stubbornly expect does not materialize. On the contrary, the schism coagulates; the paths that were to lead to encounters are blurred under a thicket of insults and expletives. And they are already so many and the uproar is so big that it is difficult to determine who threw the first chalk. Lucidity is needed, but it trickles down the gutter.

We have lost the compass. Life and death seem at stake every time someone has something to say. Some cry out for or against the flight of Yunior García Aguilera. Others defend tooth and nail or with more tooth than nail, the spectacle of Yotuel Romero and Beatriz Luengo at the Latin Grammy awards ceremony, confusedly confronting those who criticize omissions and the persistent specter of coloniality. The triumph of the song “Patria y vida” is celebrated at full blast, competing with those who prefer to dance the cha-cha or those who insisted on following Iván “Melón” Lewis’ fingers on the keyboard. Because we almost forgot, in the hubbub, that three Cuban productions were awarded this year: the song “Patria y vida” composed and performed by Descemer Bueno, El Funky, Gente De Zona, Yadam González, Beatriz Luengo, Maykel Osorbo and Yotuel and the albums Voyager, by the talented jazz musician Iván “Melón” Lewis and Cha cha chá: Homenaje a lo tradicional, by Alain Pérez, Issac Delgado and the Orquesta Aragón. Not everything is “Patria y vida.” Between one slogan and another, there is room for much more.

All the awards and all the music and all the proposals should be celebrated and criticized and above all heard equally, in the very center of a street free of all threatening tension. I imagine a street open to all Cubans, whatever side they choose, and to those who are allowed to express the reasons that each one has for happiness or indignation. Although the joy of Cubans, these days, is hardly complete. But an effort is made. We cling to mild joys, knowing that we will not be able to completely erase sadness. Nothing is absolute. Neither sadness nor joy. There are so many nuances between one and the other. It would do us good if we could linger on them instead of having to run to the opposite trenches with word flamethrowers. But that would be to enter into dialogue and, I have already said it, I do not see this coming. Neither here nor there.

Neither does peace. Because while Cubans everywhere go a little deeper day after day into the impossibility of a respectful reconciliation, for me, yes, I am Cuban, but that I am to the same extent that I am a black woman, it seems to me It’s even harder to get some asleep ever since Kyle Rittenhouse was exonerated a couple of days ago from the murder charges against him, after he murdered two protesters from the Black Lives Matter movement in August of last year. His victims were two white men, but Rittenhouse had come out with his rifle to confront protesters against police brutality and anti-black racism. His acquittal confirms that the lives of black people matter little in American society, and in many others.

I sleep badly because Cuba hurts, but also because my son’s black body is always exposed to abuses, anywhere in the Americas or Europe. I am a Cuban black mother and right now I think of the other Cuban black mothers. Many have their children sleeping in prisons. Here and there. Others fear for them. We are all always exposed to violence and injustice, but I no longer believe that anyone dares to discuss what is a fact: for blacks the neglect is always greater. Every mother suffers in the face of the possible or real aggression that her children may suffer.

Yotuel in his speech thanked his mother for the award received and dedicated it to all Latin mothers. The mother of his children and wife, Beatriz Luengo from Madrid, cried on stage because of the emotion and also, as she said, because at some point her social networks were interrupted and she received threats, “with a newborn child,” she stressed. Tears that have moved many. Tears that however did not spoil the makeup nor will they be remembered other than her intense blue dress, with Celia Cruz’s face stamped on it.

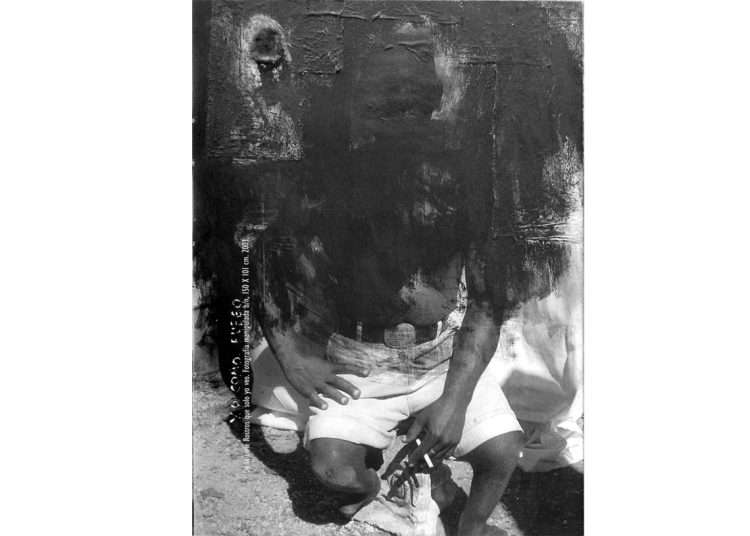

Ay, Yemayá! Carmen Fiol, from the Olympus of designers, look the other way. Beatriz’s dress and Yotuel’s cape, the flag, the tears.… The mothers.… The Cuban mothers.… The black Cuban mothers.… And their tears, which never appear either on the Mesa Redonda TV program or in the Otaola program, or in the Grammy stage, as well as the Lucas stage. Nothing is known about them. Nobody talks about them. Unless their tears are convenient for someone else, they nurture greater purposes, support agendas that were not drawn out by black women or were blacks called. Utilitarian tears. That is why the simple and little recoverable tears of the black mother matters little to the heads of ceremony, the black mother who only fears for the increased vulnerability of her son, the one whose back will resist the most blows, whose sentence will be more severe than that of others, the one who will rarely receive pardon and absolution, who will not be saved by flying to other cities with a more temperate climate. That tear lacks symbolic capital; it is as expendable as the body of the blacks that they both use like cannon fodder. Disposable bodies that of the son and the mother, because in the end it will not be she, the black woman, who will be chosen to express on stage her experience and that of her children.

The saddened and silenced black bodies pile up, disappear, will end up being forgotten. Just bodies. Meanwhile, incorporeal, some black characters act under the bright light and the rhymes continue sounding and the strong colors and the vain gesture fixed by the cameras stay stuck in the mind. The impresarios smile. The show has been a success and after the applause here we are still deafened, under the clamor that does not let us think, that distances us from what came first and should never have stopped being so, what they tell us animates the spirit of the song, of the motto and fanfare.