To say the least, Ángel Ramírez’s work is, for me, disconcerting. The pieces — engravings, paintings, altarpieces, sculptures, objects… — are made with such subtlety and good taste that they contrast with their entertaining, casual tone, like walking around the house.

I have written the above, and now I doubt. Is solemnity the exclusive packaging of “profound” contents? In other latitudes, perhaps; but in Cuba, the solemn and absurd are synonyms. And if we Cubans fear anything, it is making a fool of ourselves. It doesn’t mean that we don’t abundantly incur ridicule, but we assume it sadly, contritely: we are the fodder of soap operas and boleros. Our antidote to ridicule is the joke, the ironic comment, the scathing quote, the silly self-recognition. And so it goes.

Just because Ángel Ramírez’s work baffles me doesn’t mean I don’t like it. I defend it with passion, because I find in his work an indefatigable effort to give the status of greater art to what we believe to be nothing transcendent, that here and now that overwhelms us and in which we must make arm strokes, reinventing ourselves over and over again, so as not to sink to the bottom.

Ángel Ramírez (Havana, 1954) is an empathetic chronicler. He has the sharpness, intelligence, and sensitivity to engage in intense day-to-day dialogue from the side of the “other,” who is himself. His art, although largely nourished by popular humor, is not “folkloric”; if anything, anthropological, because it delves into the ins and outs of the collective being, which constitutes, ultimately, its raw material. It is reasoned art, of fine making, where there is a small place for chance. It is mental, but not cold; it is intellectual, but not obscure; it shuns conventional beauty, but generates great aesthetic pleasure. It is such good art that it is impossible to qualify.

I consign here a few data from his extremely rich curriculum, because what it is about is giving him a voice, showing part of his work.

Graduated from the Higher Institute of Art (ISA) in 1982. His work is part of private and public collections in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Argentina, the United States, Finland, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Colombia, Holland and Poland.

He made his professional debut in the plastic arts in 1982, with the exhibition Grafías (Galería L, Havana). From 2018 is Soft Frame, collateral to the 13th Havana Biennial. Between that and this exhibition there are 30 or more personal exhibitions that have placed him as a top-level figure within the panorama of national culture. A condition that no one has conferred on him, but rather his stubborn, quiet work, of Spartan ethics. And I say no more. I leave him here.

On a certain occasion you wondered if your work would be, perhaps, something more than a game with yourself.1 Do you still think that way? Don’t you give it importance in the discussion of our contemporaneity? Don’t you see in the work a more or less thorny path towards transcendence?

I don’t think I have marked any milestone that would allow me to dream of transcendence. Of course, I remember with satisfaction good moments along the way, specific works that, when I see them again, over time, I still like. I remember with pleasure the opportunities that my profession has given me to see art of all times and in different places, with open eyes and head. I was lucky to have very good students, whose successes and sure transcendence really give me great pleasure. Lately — it must be age — I’ve started to think about the fate of those works I’ve created in these 40 years of continuous work; some are better located than others, there are also some with no destination in sight; and yet, I don’t stop working on new pieces.

When does medieval iconography, basically from the Romanesque and Gothic periods, come into your work? What expressive possibilities does this resource offer you?

When I graduated from the ISA, and even before, I moved within a certain expressionism, and everything I did was engraving. Expressionism, which somehow came to me from Antonia Eiriz via Tomás Sánchez, was no longer used, and engraving, less. In the 1980s, there was a lot of dislike for engraving because of the “excess cooking,” because it was extremely technical and because the break with the poetics of the 1970s (the lyric of the Revolution) was being imposed, which gave way to an art where the content, the conceptual, anthropological research was valued more. So, in that context I decided to continue making engravings under the premise that the means is not what determines the character of the work; and I still believe it, I was proven right by much of what was being done around the world. On the other hand, I think I have given, from the beginning, more weight to the content, to the story I’m telling. I use the form as a support, and the means, as a resource.

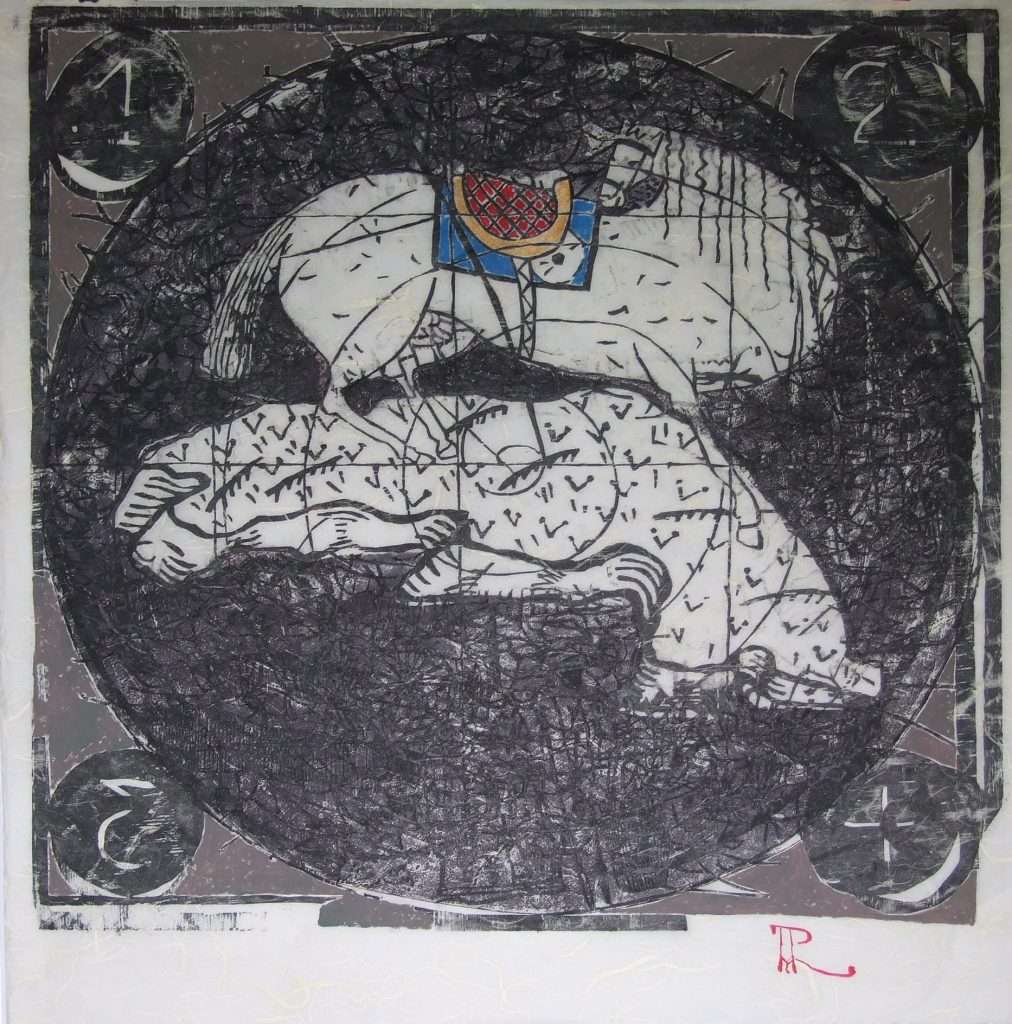

In the crisis of the 1990s I felt that we were stuck in our Middle Age (the slow tempo, the artisanal solutions, the precariousness, the very vertical organization of society…). Transportation was especially included in that package of difficulties. So I stayed at home and started painting, appropriating the Romanesque, Gothic, Byzantine spirit, broken characters, scratched, fire victims. That is to say, works on which time had painted, as it was doing with our cities and with ourselves. All that medieval imagery always appealed to me. Proof of this is that I was especially stocked with books to sip from during the Special Period. Over the years, I have been able to see firsthand a lot of ancient art around the world. Of these medieval images, there are other characteristics that have been useful to me depending on the moment and the intent: the inexpressive hieraticism, the inclusion of texts, the explicit representation of the hierarchy of each character and the fact that this iconography is universally known.

The first paintings had a lot of engraving, until they became more painting. For some time now I have returned to graphic visuality, even in the sculptures I’m making, where I include plugs as objects. Perhaps what interests me the least in engraving is the multiplicity, but I cannot and do not want to part with it, nor its history nor its culture.

You have made pieces together with Belkis Ayón, Chocolate and Luis Cabrera, among others. Did this dialogue with diverse poetics have a conjunctural nature or could it be extended to the future?

With Luis Cabrera I made a batch of pieces under the title Una serie de cosas. It was all a divertimento. Alternately, one began to draw the lithograph without the presence of the other, who then finished it. The word “cosas” (things) always appeared, and on that we did agree, with all its arsenal of ambiguity. A few years later (in 1997), Belkis Ayón and I were invited to exhibit in Japan, and the gallery owner asked us for a piece between the two of us to tie together two such different aesthetics. The process was very entertaining, thorough and a product of dialogue. We titled the work Dando y dando.

In 2004 I began to attract a group of colleagues, almost all of them engravers, to put together another series under the same name of Dando y dando, with the intention of putting each one’s own stamp to play with my way of doing things. In this case, I proposed the figure of a king as a constant, so the show would achieve unity and a raison d’etre. It was very gratifying to have the positive response of more than 20 artists, which I thank everyone for. At the opening there was a toast with coffee with milk and bread and butter, for being classic pairs, such as Adam and Eve or the duo Los Compadres. The expo was also a tribute to Belkis, who had passed away in 1999.

The project is open; in fact, it has grown. I intend to work on new pieces based on continuing to confront aesthetics with the predefined, thought-out, agreed-upon intention.

A central area of your work can be described as humorous, ironic and even sarcastic. Are those traits of your character or do they belong to the character that every artist assumes when facing the creative act? In literary theory many efforts are used to explain that the protagonist of the work written in the first person is not the author, but a character.

I headed for engraving, a resource or means full of surprises that requires time, technological discipline, order. There is the custom of putting a title at the bottom of the print; for me it was the awakening of interest in relating text and image, and to do so avoiding descriptive titles of the landscape with a dog type, where you can see a dog in a meadow. The idea was, then, to seek unity, a dialogue that resorts to the absurd, sarcasm, irony. Of course it weighs a lot that humor was part of my environment since childhood, especially on the side of my father and his family, who were talkative farmers, witty, with sharp phrases, despite having, in general, little education.

Early on I thought that humor was a substantial component of what is Cuban, but later I have been able to see that we shouldn’t think we’re the only ones. The truth is that humor, with its local hidden message, is in the DNA of humanity and even in other species.

Seeking to find the appropriate way to tell my stories, I have been chasing well-known images with proverbs, common phrases, or from one or another rhetoric. It is pure recycling, as much as when I add borrowed objects or supports. On several occasions the set can arouse smiles, but what I would like is to move ideas. I have, however, among many limitations, that these texts, plays on words cannot be translated, at least without losing the point. What does it mean for a Chinese, a Pole, or even for a Colombian, Café de la bodega?

State the artistic family to which you belong, those authors, Cuban or not, who have influenced you notably, even when this is not made explicit in the work.

I’ll just give you a group of names. In fine arts, the portraits of Fayum, Acosta León, Antonia Eiriz, Raúl Martínez; in sculptures, Díaz Peláez. In the world, a lot from Mexico, Les Luthiers, El Greco, Mondrian, a lot of cinema, African art, Toledo (the city), Saint Basil’s Basilica in Moscow, New York, Michelangelo’s slaves, a hotel in Sweden full of art. I have 90% of what may have whispered something in my ear.

I don’t feel I’m part of any group. I was old when I got to art school, so I was a little younger than the professors at the ENA, and I didn’t assume the aesthetics of that generation. Nor did I deny it. I was not part of the generation of the 1980s, with whom I shared classrooms at the ISA. Anyway, I said that I’m a degenerate. In any case, I feel more in tune with the diversity that occurs from the 1990s.

Several times you have represented Saint George, the Catholic character who is in a perpetual fight with dragons. Why the predilection for that saint? What are Ángel Ramírez’s dragons?

There are dragons everywhere; and when not, they are invented. It would seem that evil sustains and justifies good; and vice versa. At one stage I used the figure of Saint George a lot precisely because of the myth’s Manichaean character, but what I was looking for was precisely to blur the limits of good and evil (how far is one within the other?). I also used the saint to face other dragons of everyday life, of the here and now. The essential problems of humanity have been the same since the beginning of time, it changes more or less how they manifest themselves and the tools with which they are faced. Given the number of representations that I have seen of Saint George (the most, stripped of drama and without apparent physical effort of the contending parties), it makes me doubt the effectiveness of the saint in his endeavor, or it is also likely that he will resurrect the evil bug, although with a renewed appearance.

Due to the elaborateness of your pieces, due to the conceptual density that many of them possess, it is difficult to associate you with the romantic idea of the inspired artist, snatched away by a breath of revealing creativity. Do you think out the works before making them? Is there inspiration? If it exists, what is inspiration for you?

This matter of artistic creation is approached through very different paths, with different objectives, and all of them have given great works and also expendable works. In my case, passion, inspiration, the search for beauty itself are ruled out; also, respect for a certain formula. My work goes more for what is thought out, even when in the process I exploit the accident, the casual in the making. The randomness of the realization that I impose on myself leaves me time to think, to put together my story. I really enjoy the process, there are several moments: the title or text that will be part of it takes me days, and it can be outlined until the last moment; looking for the image, posing it. Then the realization is a matter of trade. I also enjoy the technical part, devising mechanisms, taking on challenges in that sense. I have been told that I have the head of an engineer (he was an engineer). I don’t think it’s that much.

Among the thematic points of your work is the use, acceptance or rejection of power. Any power. Were you a rebellious teenager? Do you have trouble accepting authority? Do you consider that since the beginning of time the exercise of power is a generally abusive practice?

My mother had her authoritarian, controlling component. Furthermore, I am an only child. From the end of my childhood, and for a long time, I was linked to the Catholic Church, which put more emphasis on fearing God than believing in him. In any case, my rebelliousness has been of low intensity and has consisted in not being very sociable, in being, to date, deeply atheist, and in not liking to be like others. I have never followed any fashion, and the worst seems to me to be the fashion of living carefully slovenly. The poses and the excess of perfection annoy me, precisely because of that.

Much of my work deals with the theme of power, of the patriarch, who can be a father of a family or an emperor, and he continues to be a person with his ideas, his pains and his fears. Of course at different levels. The goodness of a king can reach many, as can the chaos, cruelty or disorder that he is capable of. We are marked by the powers that fly over us and, at the same time, by the power that we exercise from our level.

If you were given to collect Cuban art, which artist, period, school or genre would you privilege? Why?

I have a very small collection of works from friends, almost all graphics. But I don’t have the space or the economy to collect art. I don’t have that hobby of collecting, it’s the truth, when I’m in front of a work of art I think that at that moment it’s mine, and I enjoy it to the fullest.

I regret that we don’t have a cabinet of prints where the most relevant of Cuban engraving can be preserved and consulted. That would be an institution for which I would love to work. If I could afford it (space and economy), I would like to have a lot of old tools, the kind that are an extension of the hand thanks to intelligence.

How do you relate to the market and critics? Do you feel sufficiently cared for by one and the other?

I have had a bad relationship with the market. I suffer, at least, a couple of little details against: 1) I belong to a group that believed in utopia, the collective was ahead of the personal and art was more to communicate, enchant, participate, than a commodity. There are several of us who have not been able to handle the issue, this trade takes as much or more work outside the workshop pushing the work, than inside. 2) I am given to making works with a very marked formal diversity, something that the market does not like. Many people (including gallery owners and other institutions) are looking for a painting like the one their neighbor bought last month, and I rarely have it.

Surrounded everywhere, 2017. Acrylic on canvas, gold leaf, and wood, 170 x 174 x 25 cm.

Ask me if I want soup, 2016. Oil on canvas, 94 x 81 cm.

He is she, 2019. Wood assembly, 57x 85 x 84 cm.

Hair standing on end, 2015. Mixed media on wood, 140 x 65 x 43 cm.

End of utopia, 2016. Oil and gold leaf on canvas, 173 x 208 cm.

I went through Sol and it was on fire, 2015. Manipulated xylography, 68 x 64 cm.

On the other hand, the critics, making use of their perspicacity, have not paid me much attention. I can still tell you that I have been able to live from my work and feed my family. And as for critics, when they have said something, it falls within the favorable.

***

Notes:

1 Catalog AR, Italy, 2003. Pag. 2.