“Maestro, how are you. I have followed your footsteps thanks to Drexler and I am amazed at what you do. I wanted to know if for some reason you would pass through Miami in the future. Or where your base is, to meet you one day and be able to see the possibility of taking a course on décimas. A strong hug.”

This was the first message from Juanes that I received, via Instagram, in May 2019. Imagine my surprise. Who doesn’t know Juanes? The Colombian artist who accumulates the splendid number of 25 Grammy awards and whose success transcends the borders of the Spanish language. (He has fan groups in Germany, Poland, France, Australia, etc.). As they say in Spain, I went crazy. Juanes wanted to take a course with me!

Illustrious students

I already had a beautiful portfolio of illustrious students within the world of song (Drexler, Rozalén, Zenet, Ruibal, Vicky Gastelo, Gema Hernández, Nano Stern, Pala, Marta Gómez, Pedro Pastor, Mr. Kilombo and many others; by the way, only a few Cubans: only Gerardo Alfonso many years ago and recently Amanda Cepero), but Juanes arrived, as Drexler would say, “from another galaxy.”

And my response was immediate: “Dear and admired Juanes, what a pleasure to receive your message, what a joy that you know my work, and that you like it. I live in Spain, and I don’t know Miami, but I will be happy to organize a course with you. It would be beautiful.” And it really was, has been, is being!

A few months later I went on a tour of New York, Boston and Puerto Rico, but the trip to Miami and the class project were aborted because our agendas did not coincide: he was traveling. Juanes insisted on lessons with me, and I was still happy with the idea of materializing it. But then something happened that paralyzed the world: the pandemic arrived. We also ended up trapped, I in my house in Seville, he in his house in Miami. And at this stage, which was a real social, professional, and domestic calamity, we saw an opportunity, ugly, but ideal, to start classes.

Oralitura Academy

I was precisely immersed in my online teaching project, Oralitura Academy, with daily courses on all kinds of subjects (improvisation, décima, song, rap, theater impro, oral narration, etc.) and of course I opened a space (a time) for classes with Juanes. Two or three days a week we met via Zoom. And in the first minutes we talked about life, the pandemic, children, family, everything that worried us, and then we immersed ourselves in the class, that is, in the Pimienta Method.

We started from scratch. He wanted to start from scratch. He wanted to discover and learn everything about the décima. The first thing that surprised me (I think everyone who knows him) was his humility, his transparency and his desire to learn “for real.” Those of us who are teachers know it: there is something in the look of good apprentices that leaves no room for misunderstanding, that is told with the eyes: “I’m here, teach me, I want to learn everything you know.” And that type of student conquers you, makes you fall in love, makes you a better teacher than you are, because you learn with them to teach better.

The Pimienta Method (the same one I used to create a Chair at ISA in 2000 and more than 70 improvisation schools in Cuba as of 2003; the same one I have used in Spain since 1998; the method used ― with a book ― in most schools of improvisation in Latin America (in Puerto Rico, Colombia, Panama, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, even in Brazil); the Pimienta Method, I mean, method and homonymous book, is a compendium of linguistic and poetics games created by me for the development of memory, vocabulary, the ability for rhyme and synonymy, the mastery of metrics and stanzas, the writing of the décima and finally improvisation.

In love with décimas

But, watch out!: Juanes didn’t want to learn to improvise, that was the first thing he told me. He just wanted to learn décimas to use them “as raw material” for his songs. And that’s how we focused on the classes. We spent several months during the pandemic, two and three days a week, happy, he with his learning, and I with my teaching, both “playing at being poets.” And I no longer remember at what point in the course he invited me to write songs together.

He told me about his new album project. He told me about his daily life. And of the pandemic. And of the family. And how he felt the need to tell and sing about all that, but that he wanted to do it in décimas, because he was in love with décimas, just like two of his great references, Jorge Drexler and Joaquín Sabina. Thanks to the two of them, he told me, he had discovered me. And he had discovered that the décima was (is) a beautiful stanza to make songs.

I agreed, of course. I told him that I had been writing song lyrics in décima for several years and had collaborated with various singers on albums and concerts. Songs with my lyrics (décimas and sonnets) have been made by Colombians Pala and Marta Gómez, Chilean Nano Stern, Cubans Manolo Bas, Bárbara Milián and Rubén Aguiar, Mexicans Memo Briseño and Frino, Spaniards Fran Fernández and Zenet, to name some examples). And there are many international artists who have incorporated the Spanish classical stanza into their repertoire: Drexler, Kanka, Ruibal, Pedro Pastor, Mr. Kilombo, Pia Tedesco, all of them after passing through my classes.

Writing songs

In this way, Juanes, one of the most successful Latin Grammy Award winners, the Colombian rockstar with his own star in the Latin Hall of Fame, also entered the group of “humble artists” with whom we have entered the kingdom of Espinel, Lope, Calderon, Sor Juana and Nabori. And so we started writing songs. In all, eight. And of those eight, four will see the light of day on this new and incredible album called Vida cotidiana, which has begun its adventures with the premiere of one of our co-written songs: “Amores prohibidos.” Others will come later: “Vida cotidiana,” “Mayo,” “Semilla.”

I confess that I have learned a lot with Juanes, as much or more than he with me. I have learned how one must be when you are an absolute professional in what you do: how success is the result of a conscious investment of time, patience, work, humility, trust, and more work, a lot of work, with love all the time. That is why it has taken Juanes almost three years to bring out the new album.

If you are wondering how the process was, the method of working with four hands; well, sometimes he came only with the idea, sometimes he brought me some verses, sometimes the first draft of the décimas, and we got down to work. But after the lyrics were finished, almost every week Juanes called me or wrote to review the text, to change a verse, a word, an idea.

He surprised me (happily) at how meticulous he is. The changes were sometimes due to mere phonation issues (how it sounded), sometimes due to semantic load (saying the same thing in another way, to make it more universal, for example). Another teaching of Juanes was this: he did not move a comma without counting on me, without consulting me. Even about the song titles! And he sometimes called me on WhatsApp or Zoom so that I could hear the drafts of the melody. And he sang them to me a cappella. What’s more, he accepted an invitation to my Oralitura Academy and ― to the amazement of my students ― sang one of our songs (a draft) in class.

He reminded me of myself when I read fragments of my novels to family or friends, to suss them out about that textual embryo, which will later be another. There are writers who hide the texts until they go to press; there are others, like me, who like to grope the readers. Juanes, in the song, resembles me. And I savored the whole process like a small child. Oh, and the most important thing: all this was without knowing each other personally, without ever having seen each other!

Personal meeting

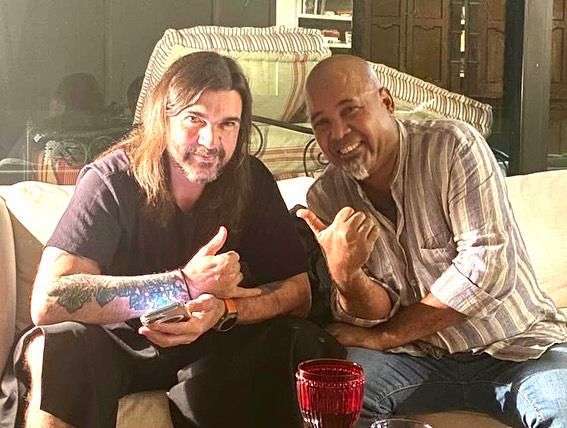

Our friendship grew and consolidated as we worked in class. There came a time when it seemed that we had known each other all our lives, when in fact the only thing that united us was music and the décima (via Internet). That is why our first personal meeting in Medellin (his hometown, my favorite city in Colombia), in October 2021 (almost two years after his first message!) was so effusive and exciting. And it was the first time that I improvised in direct, in that video that is going around the networks: a glass of wine, some friends, Juanes recording with his cell phone and me, décima at the ready, doing my bit, was enough.

The second time we met, he took me on stage with him, no less than at the Starlite Festival in Marbella, before thousands of people. He sang “Y nos dieron las diez,” by Sabina, and I improvised décimas that joined on the same Malaga stage ― oh, Espinel!, in your land! ― two authentic rockstars: the one from Úbeda and the compatriot. Yes, again the décima weaved the magic.

The third time we met was in Madrid, just two weeks ago, when he traveled to receive one of his many awards ― LOS40 Music Awards 2022 ―, already with a date for the world premiere of “Amores prohibidos” and with a copy of the video clip in a tablet for me to see. Beautiful video clip, by the way: futuristic, poetic, with surreal and even psychedelic touches, very much in tune with the theme. That afternoon we ate alone in Plaza Santa Ana, happy, and once again we talked about music, poetry, friendship, family, everyday life. Nothing extraordinary: what friends do.

Each verse, each rhyme, each image

Juanes has already told in several interviews how “Amores prohibidos” came about and why: “It started at that time of the pandemic. One day I woke up in the morning to read the press and found an article that talked about what was going to happen to the people who couldn’t see each other because of the confinement and wondered what would happen to those forbidden loves. It made me curious, and that’s where the idea for the lyrics began.”

And one day he called me, told me about “the idea,” and we began to work on the lyrics together, in class, that is, to write the décimas “live,” through the screen. Verse by verse, idea by idea. I remember his emotion and his happy child’s face with each verse, each rhyme, each image. Well, both our faces. Working like that is a delight.

I confess that for me it has been a fiesta and an apprenticeship. I was surprised from the beginning, for example, to discover that Juanes was clear that he wanted to use the stanza “as raw material” for the song, without fear of breaking the structure if the song required it. And I, of course, gave him the green light.

This is one of the lessons that working with Juanes has left me and a concept that I have passed on to the rest of my students: writing a décima to make a song does not necessarily have to end as “a song in décimas.” Juanes told me (with his own words) that the décima itself, due to its formal perfection, already raised the bar (lexical, thematic, prosodic, musical), so that, from that bunch of good verses and good ideas, the composer could fish, select, accommodate, rearrange to enter another genre, the song genre.

Let’s say that the décima belongs in its own right to the “poetry” genre, and that when traveling to the “song” genre, it doesn’t have to keep its structure of a literary music box. The musician has licenses, as the poet had them before, as we have them. Luckily (another of its mysteries) the décima is a flexible stanza, almost fractal, poetic and musical in equal parts.

The song

Regarding “Amores prohibidos,” musically speaking, the words of the album’s producer, Argentine American Sebastián Krys, are illuminating: “I think that Juanes has reconnected with his innovative and audacious composition that defined him at the beginning of his career. This song sounds 100 percent Juanes and at the same time it is unlike anything he has done before.”

The song has already accumulated more than 400,000 views on YouTube alone in the first two days. Although beyond the quantitative, I am left with the opinion of my admired Jorge Drexler: “I am so excited listening to it. The song is very good. And I love how it handles the structure of the décima and opens it to close it. The décima is very well broken. Very interesting how he separates the last quatrain and suddenly leaves a free rhyme: ‘a threat’.”

“Amores prohibidos” is a song co-written in décimas by Juanes and me, a rock cumbia with whose single and video clip his new album, Vida cotidiana, is released. Until now, my relationship with music had been different: I wrote lyrics and others put them to music, or some musicians selected décimas, sonnets or poems of mine and set them to music. There are also some songs with lyrics and music by me. But with Juanes everything has been different, new, exciting. These four songs mark a before and after in my way of understanding songwriting. And décimas. Thank you, Juanes, once again. See you on the dance floors.

And as a climax, the lyrics:

AMORES PROHIBIDOS

La cama rectangular

y las prohibidas pasiones

alimentan las canciones

y nos ponen a sudar.

Se echa tu cuerpo a volar.

La luz no quiere hacer ruidos.

Y aunque estemos escondidos

Y aunque nadie nos lo diga

habrá algún Dios que bendiga

a los amores prohibidos.

Y entre te quiero y te quiero

no veas una amenaza

habrá algún dios que bendiga

a los amores pasajeros.

Yo quiero lo que tú quieres.

Tú quieres lo que yo quiero.

La luz entra en línea recta

a través de la ventana

y mi cama en la mañana

una geometría perfecta.

Qué locura predilecta

entre tu piel y la almohada.

Pasa la luz apagada

descalza sobre tu pelo…

Habrá algún Dios que bendiga

a los amores prohibidos.

Y entre te quiero y te quiero

no veas una amenaza.

Habrá algún Dios que bendiga

a los amores pasajeros

Yo quiero lo que tú quieres.

Tú quieres lo que yo quiero.

Si algún día nos juntamos

y tú quieres algo más

disfrutemos y olvidemos

lo que piensan los demás.

Si algún día nos juntamos

como el colibrí y la flor

aunque sea pasajero

disfrutemos nuestro amor.

(Guitar solo)

Habrá algún Dios que bendiga

a los amores prohibidos

Y entre te quiero y te quiero

no veas una amenaza.

Habrá algún Dios que bendiga

a los amores pasajeros

Yo quiero lo que tú quieres.

Tú quieres lo que yo quiero

Si algún día nos juntamos

y tú quieres algo más

disfrutemos y olvidemos

lo que piensan los demás.

Si algún día nos juntamos

como el colibrí y la flor

aunque sea pasajero

disfrutemos nuestro amor.

Disfrutemos nuestro amor.

Cómo no, cómo no, cómo no.

Disfrutemos nuestro amor.

¡De Colombia para el mundo, papa!

Disfrutemos nuestro amor.

Disfrutemos nuestro amor.

The UCLA Library doesn’t provide interlibrary loan service to people unaffiliated with UCLA.