The Old Man died so many years ago that nobody remembers him anymore. All of the streets here are paved now; all of the buildings have been modernized, except for La Terraza, where the tourists go to sit at the bar and enjoy the same food that was cooked there when the Old Man was the best fisherman in Cojímar and in the world.

A lot of people agree that the Old Man was pure fantasy, a character out of a novel, who never existed; however, others say that he was a real old man, with a boat and a fish—all real—brought down by sharks off the coast of the village of Cabañas, more than 60 kilometers west of Cojímar and about 50 from Havana.

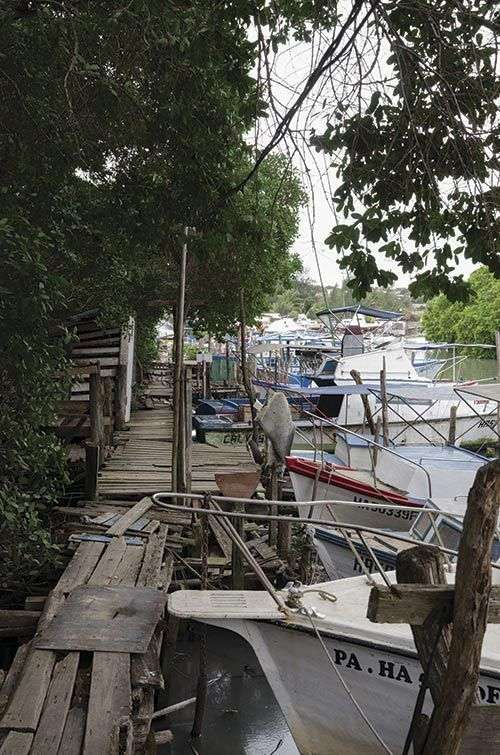

In the narrow cove, fishing boats are still anchored. That and La Terraza are among the few vestiges that endure from the mundane world of old Santiago.

Gregorio Fuentes, skipper of the yacht El Pilar and the sea-venturing buddy of the man who gave the Old Man fame and celebrity, used to go every day, not so long ago, to sit down in a corner of La Terraza and have a bite to eat, recounting his adventures to whomever wanted to share those memories. He was a strong man, with hands hardened by many years of fishing, and he had the privilege of reaching a century of life. His eyes were a reflection of nostalgia, and fantasy abounded in many of his stories.

He was the one loved by the residents of Cojímar. He, along with another man who was not born there, did not live there, and did not die there; a man who was adored not like the bronzed god that the world talks about, but the man who reciprocated that affection, and whose favorite celebration, among all others, was to be together with the fishermen of Cojímar, permeating his Nobel Prize for Literature with icy Cuban beer and rum.

“Who was that?” might be the question of any given millionaire, because Hemingway used to speak ill of them. “He was a pain in the ass,” many intellectuals would say, given that the author of For Whom the Bell Tolls did not always treat them well. “He was a tremendous guy,” the few remaining 90-something-year-old fishermen of Cojímar would say, the ones with leathery skin and sun-burned faces, whom the writer never spoke ill of.

That is why in Cojímar, where the legendary presence of old Santiago can still be sensed—“thin and gaunt, with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck”—you can find, near the sea, with head held high and a bright expression, a bronze bust of the celebrated bohemian who intensely enjoyed the strange sensation of feeling his hands aching from the fishing lines in his struggle to the death with the great creatures of the Gulf.

The smell of fish and shellfish in the stillness of July and August afternoons; the taste of sea salt on your lips in the hazy days of cold fronts; nostalgia at sunset and nocturnal languor in the narrow shelter of the port; all of these season the characteristic environment of the old part of town, a vital space for fishing nets, harpoons and hooks, a labyrinth of badly drawn-up streets on the slopes where fishermen’s huts used to precariously perch.

And the giant soul of the coastal dweller, invading that place of giant humility but also small for the torrent of big-heartedness. The living presence of the current that shaped the elements of Santiago the fisherman and demanded a magic brush to paint it.

So the artist set about working on that gift, and with the richness of his experiences and a little imagination, he began to give color to his work: He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days now without taking a fish….”