There is a notable growing interest in the world about subjects related to the gastronomy of each people, a very important part of their culture. Cuban food also tells its story.

In his travel log, Samuel Hazard referred to Cuban food customs:

The Inglaterra Hotel and Restaurant, on Prado Street, is also excellent, especially for the gentlemen, since in it they can separately take a room and eat in the a la carte restaurant…. Since what is served at the table, in the major part of the cities, in all the hotels and most of the best private homes, generally belongs to French cuisine, it is only in the rural districts that one can bona fide taste the Cuban dishes…. The daily meals of the humblest of farmers consist of fried pork and boiled rice, in the morning, replacing bread with fried or baked plantain. In the evening they eat beef, jerky, chicken and roast pork, but more usually the meal consists of roasted plantain and the national plate, the ajiaco, which in Cuba is what the meat and vegetable stew is in Spain.1

Since those times until the first half of the 20th century, the cheap restaurants of Cubans and of Spanish and Chinese immigrants, the fast food stands and the timbiriches (which sold bread with omelets, bread with fritas, a variety of fried food like those made with cod and those with black-eyed peas, stuffed potatoes, croquets, bread and pork, bread and beef steak, tamales, cracklings, sandwiches, fruit shakes, sugarcane juice, lemonade, coffee, etc.), the ice-cream carts and the vendors of churros, the pushcarts with the most delicious tropical fruits and the cafeterias, like those in high demand: El Carmelo and El Potín, as well as the economical meals of the dime stores of El Vedado, San Rafael, Obispo and Monte.

Foods like beans, soups, ajiaco, pork legs, cracklings, pork rings, fish, jerky, fried eggs, stewed meat in tomato sauce, shredded friend meat, ground beef, chicken fricassee, rice cooked with chicken, white rice, rice cooked with kidney beans, rice cooked with black beans, cornmeal, tamales, yucca with garlic and oil-based sauce, boiled cassava, sweet potato and the fried vegetables (yucca, cassava, sweet potato, plantain) constitute that palate formed from the cultural melting pot that Cuban food is and will always be, although I consider that it was the cheap Cuban restaurant which popularized our very Cuban stamp.2

In the Cafés, a deeply rooted Spanish inheritance, conceived for conversations, businesses and dates, there always had to be the cup or mug of milk with coffee, nice and crusty baguettes with butter and a wide-ranging assortment of other foods related to that type of establishment. The gathering of Cuban writer José Lezama Lima in La lluvia de oro Café and the meetings in the Café Vista Alegre, where emblematic songs of the traditional Cuban trova were written and sung, among others, were famous.

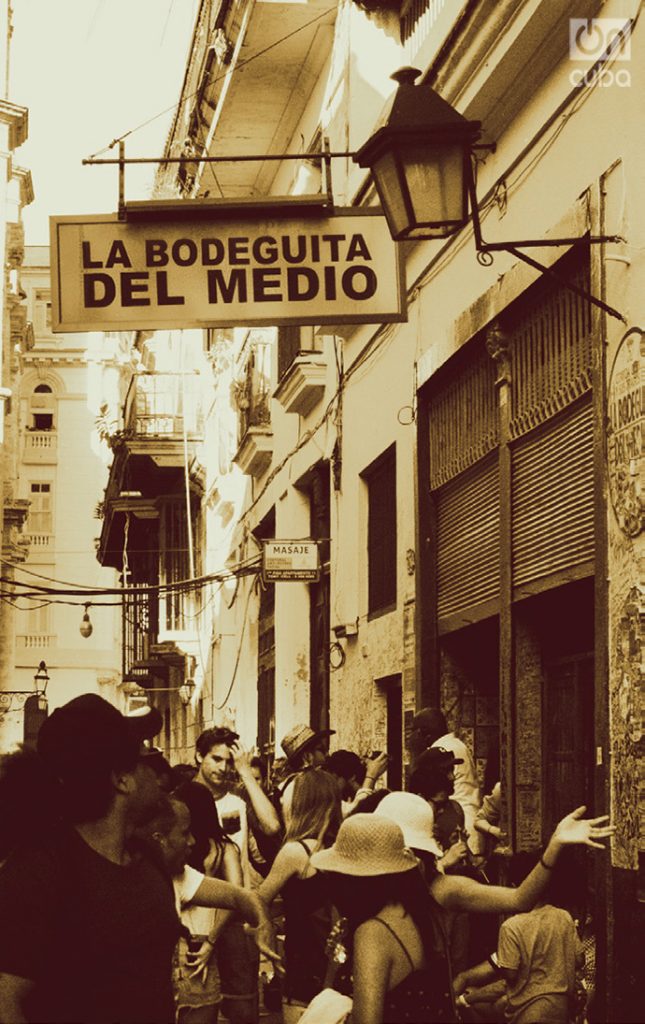

The bars and nightclubs because of their cosmopolitan and bohemian accent were the rage. In 1924 the Cuban Bartenders Club had been created, the first of its type in the world – the current Association of Cuban Bartenders. The style and professionalism of the Cuban bartender was being imposed (and today is reaffirmed). It is not by chance that some of the creations from that time are included among the classic and most distinguished cocktails in the world. We can find proof of that resonance in bars like Sloppy Joe’s, in those of La Bodeguita del Medio, El Floridita, Dos hermanos, Monserrate, Castillo de Farnés and in the Sevilla and Inglaterra hotels, among many others.

During the 1940s and ’50s, together with those popular and traditional food spaces at very accessible prices, stylized and expensive restaurants prevailed, with a predominance of international classic cuisine, in their majority for the Havana middle classes and high society and for foreign tourists: Monseigneur, El Emperador, La Torre, Floridita, Puerto de Sagua, El Templete, Castillo de Jagua, Club 21; in those of the Havana Hilton, Nacional, Riviera, Capri and Deauville hotels, and the Sans Souci and Montmartre cabarets. La Bodeguita del Medio evolved from being a cheap restaurant to a typical Cuban food restaurant and Rancho Luna (from Wajay and El Vedado) were an obligatory reference of traditional cuisine with its Rancho Luna Chicken family recipe. The Centro Vasco, Zaragozana, El Baturro and others established their success on Spanish cuisine. And, among those specializing in Italian cuisine, Frascatti, La Picola d’Italia, Montecatini and La Romanita stand out.

In 1968, as a result of the Revolutionary Offensive, the process of nationalization of gastronomic establishments, which had started since the mid-1960s, concluded. The Cafés, the fast food stands and other outlets gradually disappeared. The restaurants and cafeterias that remained open were subordinated to INIT (National Institute of Tourism). Thus began a period in which the popular gastronomy was directed at guaranteeing not just very economical prices but also social alimentation in school centers, hospitals, worker canteens and other State institutions. The Luxury Restaurants Enterprise emerged to “safeguard” some of those mythical restaurants and cafeterias from the 1950s and to create others of higher than average quality standards which was decreasing. INIT’s Department of Technical Consultancy brought together professionals in different specialties (salon, cold area, soda fountains, butcher shops, canteen, pastries, etc.), who were in charge of managing, advising and developing the old and new gastronomic establishments in Cuba.

The shortage of raw material, supplies and integrally trained professionals, as well as the diminished strategies in that sector, hindered the prosperity of Cuban gastronomy on a national and international level.

In the following decades (’70s and ’80s) new structures were established to attend to gastronomy: INIT disappeared and the Gastronomy and Services Sector was created, belonging to the government or People’s Power, associated to the Ministry of Domestic Trade, with similar functions to the already mentioned. The Federation of Culinary Associations of the Republic of Cuba was created to “dignify and train cooks” as well as hospitality and gastronomy schools like the Sergio Pérez. The Sevilla Hotel School (which existed before 1959) was modified as a Higher Studies School with different gastronomic specialties in its program. But, in general, the mimesis in the apprenticeship with emphasis on international cuisine and service continued, and still continues, which until now has conditioned the low profile of a great deal of the state-run gastronomy.

In the 1990s, Cuba had to again set its sights on the tourist industry relegated until then. Strategies started taking shape to recover the gastronomy. The FORMATUR schools were created on a national level, as well as corporations like Gran Caribe and Cubanacán, with branches for the development of gastronomy, whose methodological directives are governed by MINTUR (Ministry of Tourism). As part of Cubanacán’s structure the Palmares Non-Hotel Enterprise was created with which El Aljibe, La Cecilia, Tocororo, La Ferminia, among other restaurants, won international fame. Some new and others very well-known were “relaunched,” as occurred with El Floridita, and became part of this company.

The Habaguanex Company, which attended gastronomy and hotels in the Office of the City Historian, became a referent of prestige with its Café del Oriente, La Mina, La Imprenta, Al Medina, Torre de Marfil restaurants, among others.

Meanwhile, the popular gastronomy continued declining and the displacement of the more competent toward the tourist sector’s gastronomy was increasing.

In 1993 the Cuban government authorized the private management of some sectors. The first paladares (popular term, taken from a Brazilian soap opera with a high rating in Cuba, used to name private cafeterias and restaurants) were created. In 2013, with a new resolution, the non-state management was increasingly made more flexible and these paladares started proliferating throughout Cuba with original and multiple proposals that defend Cuban traditional cuisine, based on the rescuing of dishes and recipes that had been left in oblivion, as well as contemporary fusion cuisine.

They are luxurious and famous restaurants, some of them located in a house or an apartment building, adapted for gastronomic service (La Guarida, La cocina de Lilliam, Varadero 60, San Cristóbal, Santy, La Corte del Príncipe); or the new entrepreneurs purchase dissimilar spaces to make them functional: Atelier, El cocinero, La Guarida, Doña Eutimia.

And there are the more informal, but with a stamp that makes them unique: Ajiaco Café (Cojímar), La cuchipapa and San Salvador de Bayamo (Bayamo, Granma), Los Amigos (Santa Cruz del Norte, Mayabeque), La cueva taína (Gibara, Holguín), Paladar de María (road restaurant, Taguasco, Sancti Spíritus).

The non-state gastronomic management is growing in all the Cuban provinces and is increasingly more successful. According to the purchasing power of Cubans and non-Cubans, guests are increasing and the panorama of the barrios is changing. It’s a boom that seems to have come to stay.

[1] Quoted by Jesús Abascal López, in “Entrecomillas incluir el título del artículo”, Revista Arte Culinario, no. 2, Culinary Association of the Republic of Cuba, Aug. 2002, p. 5.

2 Silvia Mayra Gómez: La fonda y sus comidas, Oriente Publishers, En Casa Collection, Santiago de Cuba, 2017, p. 15.