Labels for a troubled political scene

The word “rafters” became global in the summer of 1994 when, in fragile boats, more than 30,000 Cubans went to sea. It was not long after the maps changed color, in the Special Period, the code with which Fidel Castro designated the mamellazo (blow) to the forehead in 1990. “Save the Revolution and save socialism” were two expressions that Cubans had not heard before. Nor a third one: “collective pots.”

That stampede received the name of “Rafters Crisis.” By mid-August 1994, more than 6,000 had arrived in the United States, compared with 3,200 who had emigrated that way during the entire previous year.

In 1995, President Bill Clinton implemented what would become known as the “dry foot/wet foot policy.” Only rafters who made landfall would be accepted into the United States.

During the crisis, with the refusal to receive them once they were rescued from the Straits of Florida, since the same year of 1994 they had begun to be sent to an alien, but not unknown, location: the Guantánamo Naval Base. Until then, its facilities had been assigned by order of Reagan to Haitians intercepted near the coast of Florida (1981); “safe haven” policy.

On May 2, 1995, the Clinton administration announced that most Guantánamo detainees would be processed and allowed to enter the United States. The crisis brought an agreement: the rafters would be returned to Havana if they did not qualify for political asylum. The Cuban government promised not to take any action against those who were repatriated.

The dry foot/wet foot policy was discontinued in January 2017 by a Clinton fellow Democrat, Barack Obama, almost at the end of his presidency and after having implemented a policy of engagement with Cuba, announced in December 2014.

The rapprochement between the United States and Cuba led, among many other results, to unprecedented talks since 1959 and to the inauguration of embassies in the respective capitals, beyond the interest sections that had functioned since the 1970s under that détente of the Carter administration.

![]()

A final decision

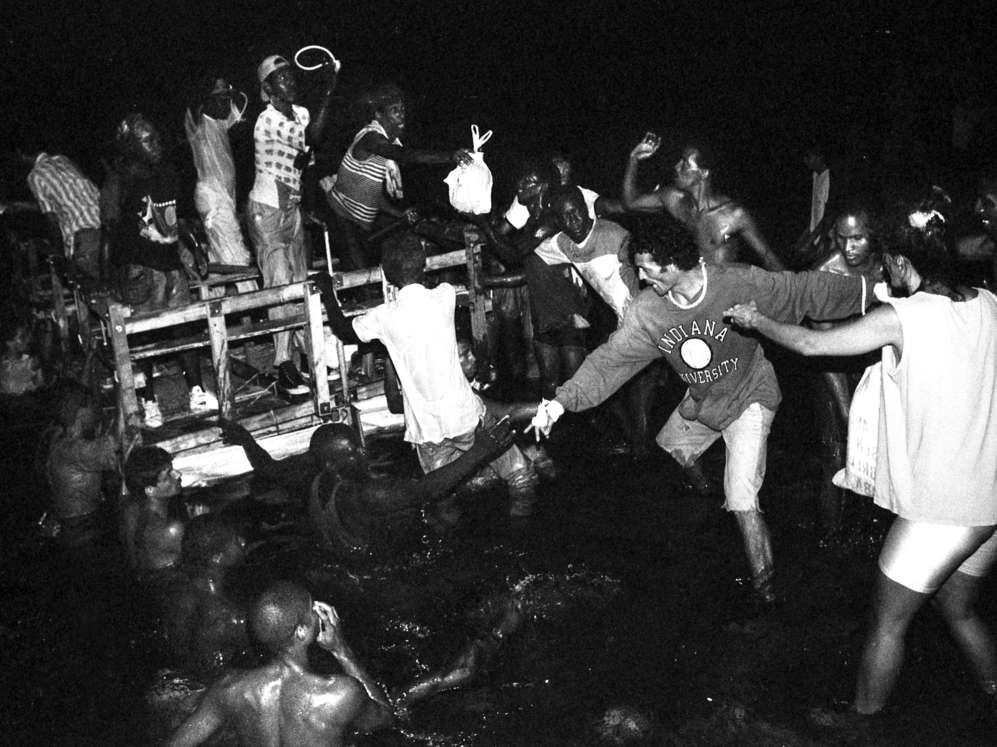

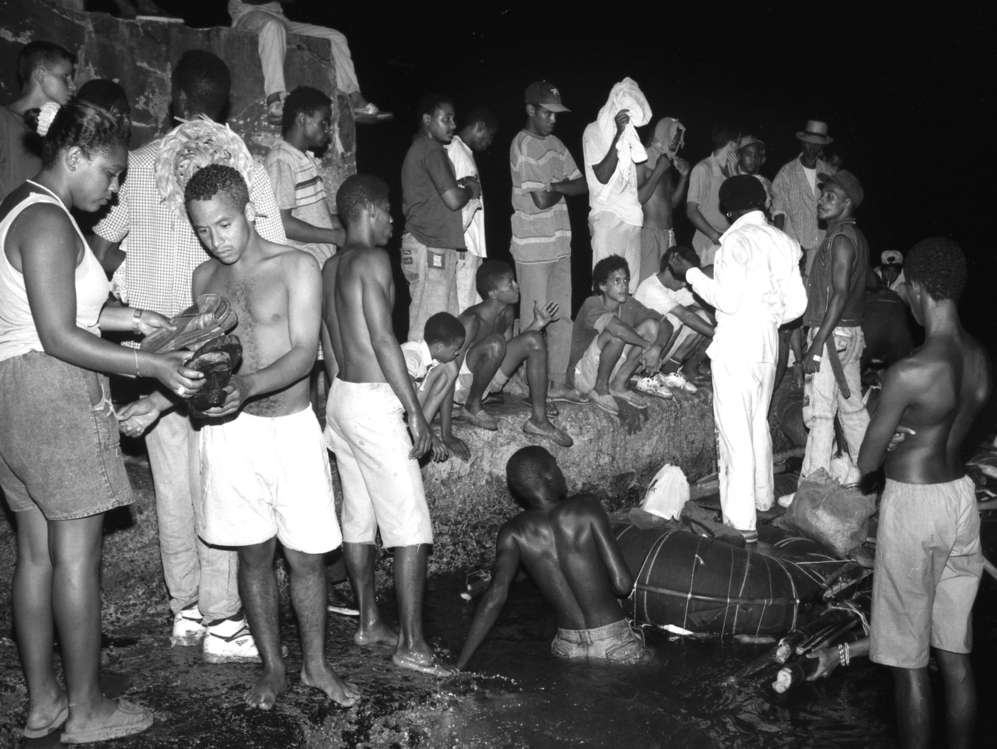

“People carried rafts from their houses to the coast. They were endless processions. There were onlookers everywhere. Relatives saying goodbye, many crying, friends saying goodbye to friends without knowing if they would see each other again. Something dramatic.”

Willy Castellanos, a photographer who in 1994 made a series on the subject, with his Nikon F3 and a 28-millimeter Zackar lens. Éxodo, documentos alternativos was exhibited in Miami in 2014, with a sample of almost thirty snapshots.

“A rafter will be rafter until he dies. Just like an emigrant he always is an emigrant. The decision they made in August 1994, for better or worse, will haunt them for the rest of their lives.”

Carles Bosch, director of Balseros (2002), a documentary that condenses seven years in the life of a group of illegal Cuban migrants into two hours. Oscar nominated in 2003.

![]()

The Elián González case

In November 1999, the phenomenon of the rafters witnessed an unprecedented event: the case of Elián González. The 5-year-old boy survived the death of his mother and the rest of the passengers of a flimsy boat at sea. Suddenly elements that had not been mixed before collided: immigration policies, custody problems characteristic of U.S. society, ethical and family issues; everything crossed by politics and, above all, by the dispute between the powers of exile and Cuba. Rebounding, Elian put the island (again) at the center of the U.S. media.

After lengthy legal disputes, in April 2000 FBI forces carried out a rescue operation to enforce the decision of the United States government to return the child to his father in Cuba. The word “betrayal” remained in the Miami environment, like a few decades before, with Kennedy and the Bay of Pigs On the other side, new songs of victory filled the public squares.

![]()

Human waves by land and sea

For Cubans, the Mexican border had never been so porous and attractive before President Obama wiped the dry foot/wet foot policy away in January 2017. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Department of Homeland Security already showed in 2015 a trend that had begun to grow since 2012: 27,143 Cubans had entered the United States through the southern border during that fiscal year, with Laredo as the favorite point of entry. 9,056 had entered through the Miami International Airport and requested asylum. More than 33,000 souls.

Several concurrences had an impact, and notably two: first, the Cuban immigration reform of 2013, which made leaving the country more flexible by eliminating a set of historical restrictions — ”carte blanche,” exit permission, etc. A long-delayed internal demand that, whatever its limitations, allowed Cubans to move with a sine qua non condition: that the receiving countries grant them a visa.

Regarding the visa requirement for Cubans, Ecuador was one of the few exceptions; although there were others, too far from the dreamed route: Botswana, Cambodia, Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan…. As of this situation, many Cubans arrived at the South American springboard (Ecuador or Guyana) to undertake a journey of thousands of kilometers to the Mexican border no matter traffickers, merchants, corrupt officials, rivers, jungles and many other adversities. They were not always successful.

Secondly, starting in 2015, the social perception began to take shape that the Cuban Adjustment Act would end because both governments already had diplomatic relations: it was necessary to hurry. It was a kind of deafness that ignored the messages from the Obama administration in the sense that there was no intention to change the immigration status, nor the Adjustment Act in Congress. It was said from the first round of bilateral talks, and various government spokesmen repeated it ad nauseam.

Added to the picture was the work of TV stations visible in Cuba through the “antenna,” as well as round-trip travelers who assured their “associates” in Cuba that the Adjustment Act was in some sort of “imminent danger.” As if to top it off, Cuban-American congresspeople who previously defended the legislation tooth and nail, turned to the third option, arguing for the need to reform it, which on the island was decoded in a popular saying: “Pick up the belongings, we’re moving.”

Six years after the ease of entry to Ecuador ended (November 2015), in November 2021 Nicaragua (a point much closer to the north than Guyana and Ecuador itself), exempted Cubans from the visa requirement. An unusual flow of compatriots began to travel thousands of kilometers by road, with coyotes, and thousands of dollars, until they reached a point on the 3,145-kilometer border between the United States and Mexico.

In November 2022, a new record was reached for Cubans entering the United States through the southern border: a total of 5,881 people. During calendar year 2022, the number reached 313,048, which was double (albeit over a longer period) the combined total number of Cuban emigrants to the United States from the 1980 Mariel crisis (126,407) and that of rafters in 1994 (32,362).

As a whole, Cuban irregular emigrants are escaping the consequences of the structural crisis of the economy, the lack of reforms, galloping inflation, the increase in U.S. sanctions, the effects of the pandemic, the inaction of migration agreements — that establish the acceptance of 20,000 Cuban immigrants a year, legally — and the closure of the Consulate in Havana after some strange sonic incidents that to this day no one has been able to explain. They were reported in the midst of the process of demolition of relations with Cuba that Donald Trump undertook from the beginning of his term in office.

A look at the figures is illustrative. Between October 1 and December 31, 2022, the United States Coast Guard intercepted 4,076 rafters. The word that identifies them is overwhelmingly associated with another: deportations, the result of those immigration agreements signed by both governments in 1995.

During the 2021-2022 fiscal year, the Coast Guard intercepted 6,182 Cuban rafters. In the same period, some 260,000 Cubans appeared on the southern border, where those deportable — unlike those captured at sea — have been swallows that don’t make a summer.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

![]()

Migrants A; migrants B

Whether by sea or by land, it is about irregular migration; but, in addition to the route of traffic and the conditions of the journey, there are other important differences. The journey over land requires the investment of several thousand dollars (inflated airfare; transportation, lodging, and meals at various points along the journey; coyote “fees,” possible bribes, etc.). A similar expense can only be assumed by those who have inherited, saved or invested in assets that they can sell. There are few cases. Others rely on relatives who finance the operation from abroad.

The rafters, although they are part of the same migratory boom, are profiled as another type of emigrant; presumably without support from abroad even on loan terms, without inherited or obtained assets, without a house, car or other valuable asset to put up for sale.

They tend to be more desperate and underprivileged people. They take to the sea because they lack the financial resources necessary to “go see the volcanoes” (traveling to Nicaragua and from there continuing their journey to the Mexico-U.S. border). Many of their faces come from the so-called Cuba B, the interior, the province, where poverty levels have deepened further after Reorganization and the pandemic.

Poverty is precisely what the rustic boats in which they venture to cross a Strait marked by the always treacherous Gulf Stream, sudden changes in weather conditions and shark-full waters.

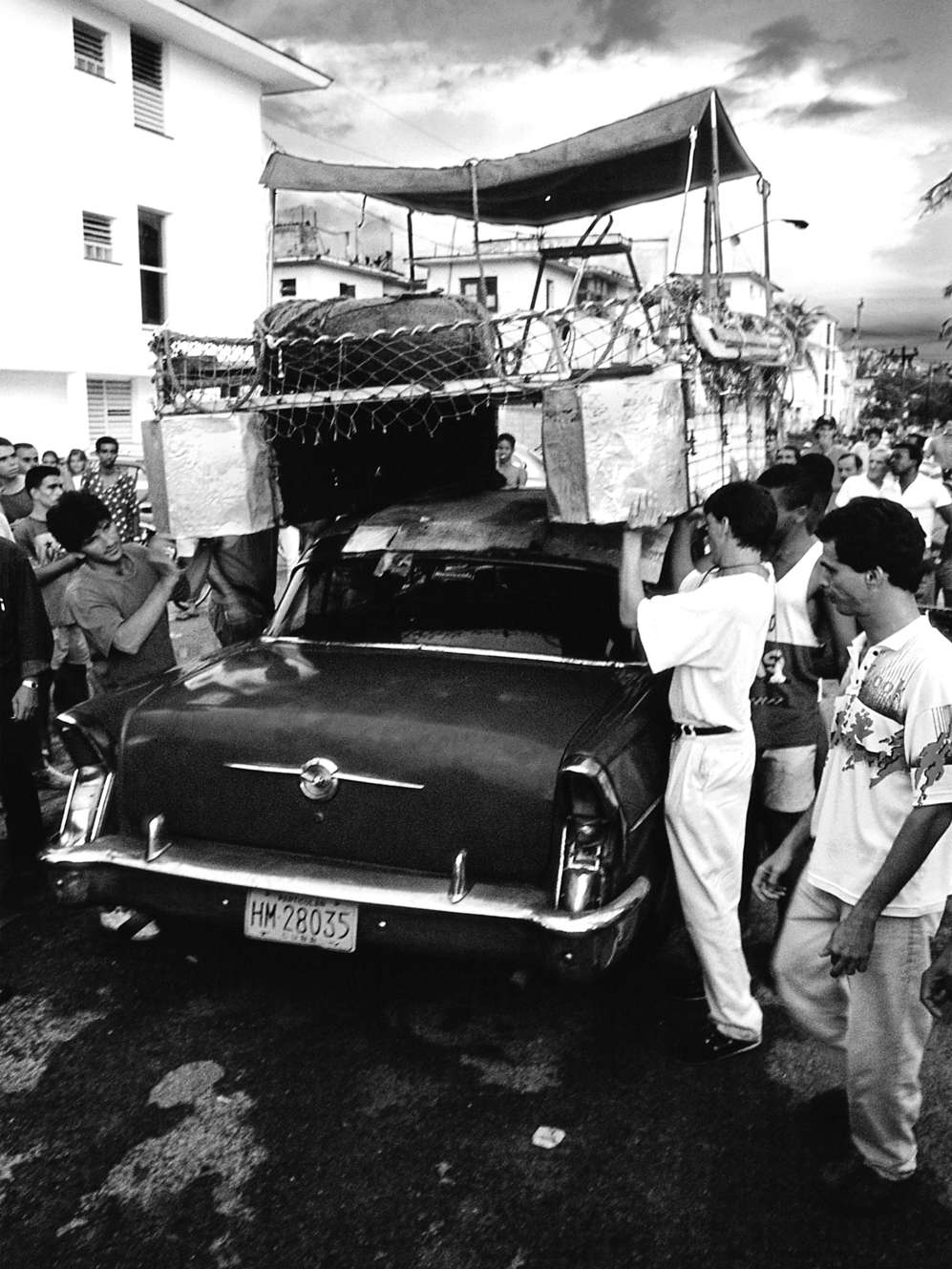

They are true marvels of wood, aluminum, polyfoam and other materials, sometimes assembled on 55-gallon tanks trying yo not having them perish in the fight against the elements. Floating artifacts — sinkable miles inland, despite precautions.

They can be ten or more days of voyage, without food or water, trying to remove the persistent impertinence of the water from the boat. With a devastating sun, especially in summer. And a proverbial darkness during moonless nights.

“We couldn’t even see our hands,” said one of them. “And the worst thing is that we felt the bugs fluttering around that floating shell.”

But this time there is something different. Before, this migratory flow was only documented — with few resources and rarely — by the press, camera in hand, aboard a Coast Guard cutter in U.S. waters. Not now. We are living through a true explosion of graphic records.

Today’s migrants carry with them new devices with which they testify the journey in photos, audio and videos, at least as far as possible. Those on both shores also have the new means. We have seen live broadcasts of raft departures or arrivals; we attend as spectators the farewell or the euphoric landing of the lucky ones.

Thanks to the records, we know in detail their equipment, the interior of their boats and we see them themselves. It is a precarious and chaotic material that we never had access to before. It existed only in the individual memory — or trauma — of those who had survived the experience. Now they are pieces of a collective memory.

We have also seen the boats that arrive empty on the coast.

The new technologies are not only being used to leave testimony, but also in order to reach the destination alive. In March 2022, a rafter was rescued on a windsurf board near Cayo Marathon thanks to his cell phone and his GPS. Barely two months later, a new figure appeared, exceptional until today: the technorafter, a young man from Varadero who crossed the Strait on a kite board equipped with a cell phone, state-of-the-art technology, a neoprene suit and a hydration backpack that allowed him to reach the other shore in record time: six hours. He recorded the journey with the help of several cameras.

He said in Miami: “I sailed every day in Cuba, I studied the weather on Internet programs, the winds, everything, everything, so that nothing went wrong. I studied every day when the wind was going to change and I took advantage of the south-southeast, which is the one that propels you towards the coasts of Florida.”

Nothing seems to deter them. Neither the dangers of undertaking the journey — almost a suicidal act — nor the insistent messages from the U.S. authorities (#DontTakeToTheSeas). Nor the assureness that they will be returned to the island after risking their lives. They continue to do so even after the new parole program for Haitians, Nicaraguans, Venezuelans and Cubans was announced on January 5, which disqualifies people who venture into illegal entry, by land or sea.

“We urge all people to use safe and legal ways to come to the United States. Please don’t take to the sea,” insists Lieutenant Ebria Karega, of the Seventh District of the Coast Guard.

From October 2022 to date, the Coast Guard has intercepted 5,590 rafters. In less than five months, a figure very close to that of the entire previous fiscal year (6,182 in twelve months) has been reached. Of those intercepted, almost all have been returned to Cuba.

The imprint

The imprint

There is information about the rafters who are intercepted and those who touch the mainland; but very little or none of those who do not. Boats that arrive empty on this side. Shoes that appear one day in the sand of a key. Documents floating in the water.

A graveyard in the sea. A historical drama with too many faces in the dark. A tragedy starring broken families, weeping and desperate mothers, irate brothers and sisters, crestfallen widowers and orphaned children.

And with indelible marks. Sometimes for a lifetime, outside or inside “the land of the free” and “the home of the brave.”