Help us keep OnCuba alive here

After 60 years of enmity, diplomatic and political fights, on July 20, 2015, Cuba and the United States reestablished their relations. A period of hope was beginning, but that time barely lasted two years. The coming to power of Donald Trump stopped the “thaw” and, with it, the perspectives of thousands of Cuban families, true protagonists of these times of more than half a century of disagreements between the two shores.

These are some of their faces and stories compiled by EFE.

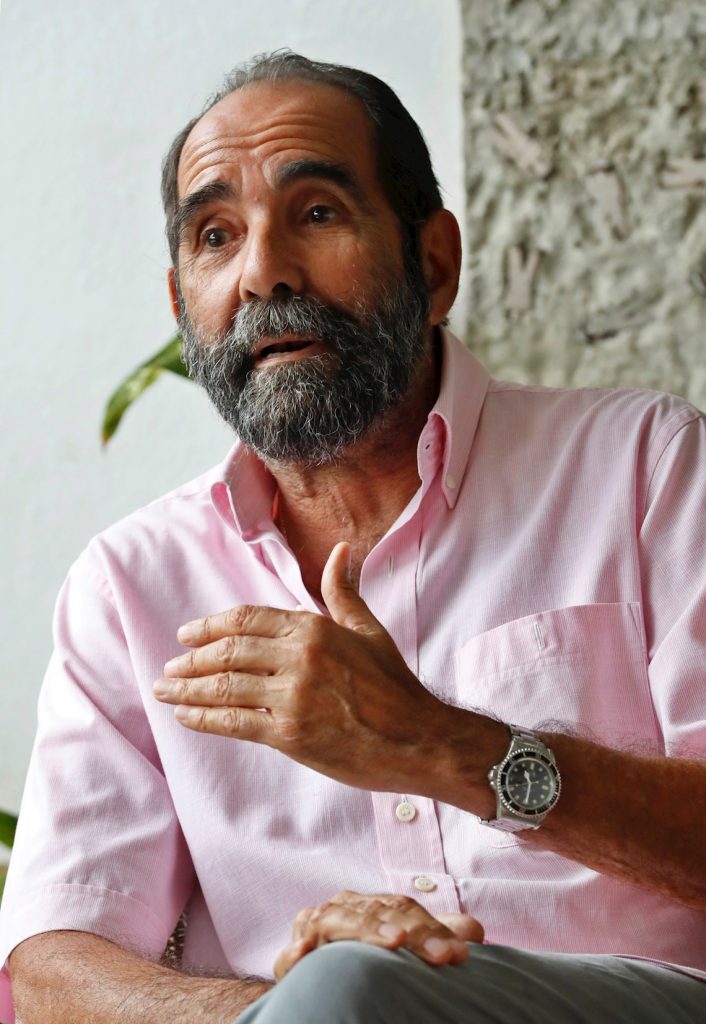

“I thought I could travel to Miami if my mother gets sick or dies”

“I was left alone at 20 in Cuba,” says José Alberto Figueroa, photographer.

His parents and siblings emigrated to the United States in the 1960s, but he stayed behind to pursue his passion, photography. He started as a disciple of renowned Alberto Korda and finally made a name for himself in the profession. For decades he communicated through letters and semi-clandestine calls with his mother and siblings.

“I was frowned upon. You were pointed out in the neighborhood’s Committee for the Defense of the Revolution as an individual related to the United States, and therefore a person without political confidence.”

In 1991 he traveled to the neighboring country for the first time to reunite with his family, and in the following years he made several work-related visits. This connection was interrupted in the 2000s, when George W. Bush included Cuba in the famous “axis of evil” and imposed restrictions.

“It was a terrible until (Barack) Obama arrived. His triumph was a great change.” In 2013, the United States extended the duration of non-immigrant visas for Cuban travelers from six months to five years, with the possibility of entering and leaving the country several times. He began traveling regularly to Miami, where his 94-year-old mother resides.

The Trump administration withdrew the personnel from its embassy in Havana and in March 2019 eliminated the five-year multi-entry visa. Now entry is limited to one in three months and Cubans also have to go to a third country to request it, leaving thousands of families in the lurch. In the case of Figueroa, his visa expired in 2018 and he didn’t have time to renew it.

“I thought that I could go if my mother ever gets sick or dies, that this aspect was resolved. I was unable to attend my father’s or my brother’s death (in the 1970s). Therefore, I said, I have that visa, I can go at any time, it’s a 45-minute flight. But that ceased to exist.”

“We’ve been left in limbo”

After immigrating to the United States, Gretel Moreno, a 46-year-old accountant, applied for a visa to bring her brother, sister-in-law and niece there from Cuba, through the Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program (CFRP). The process began in 2016 but the program was suspended a year later by the current U.S. administration. Since then, her dream of reuniting her family has been left “in limbo,” a situation that extends to hundreds of families on both sides.

“My case is one of the worst, it’s an F4, because it’s my brother and his family,” says Moreno, who lives in Miami.

This and many other procedures were paralyzed when the U.S. Embassy in Havana dismantled in 2017 almost all of its services on account of mysterious health problems suffered by its diplomats on the island, in which the Cuban government denies being involved.

For Moreno, that matter is “a pretext” because on the U.S. border “even interviews with immigration judges who grant asylum through cameras have been implemented and that works.”

“This is the same, we made all the payments in 2016 for the family reunification program and everything has been left in limbo. Apparently they are going to keep that money,” says Moreno, who paid about 1,000 dollars for paperwork to bring her family.

According to this activist from the Cubanos Unidos por la Reunificación Familiar platform, a group created in 2017 as a result of the consular lockdown and which already has 58,154 members throughout the United States, it’s a “legal government scam” involving “hundreds of thousands of dollars,” at the rate of 360 dollars for each family member claimed.

“Cubans went from having many privileges to being the least privileged in the entire world because of the wait in Guyana,” says Moreno, referring to the transfer to the U.S. embassy in that country of the processing of family reunification visas for Cubans.

“It’s shameful that almost four years later there is no solution, it’s a total lack of interest. The most important thing of all (for the Trump administration) is to bring down the (Cuban) dictatorship and that it finishes collapsing, and that it hopefully happens tomorrow, but that has led to the rest not mattering,” the woman laments.

Moreno has written to several instances without obtaining a response. “I’ve really lost hope, I realize that there is no interest in solving the problem,” she concludes.

“I can’t afford to buy food without remittances”

“Just imagine, things couldn’t get even worse. I’m diabetic and hypertensive and I need to eat every three hours, I need fresh fruit, milk, and I can’t afford it, especially milk,” says Isabel Salabarría, an 80-year-old retiree.

Isabel’s already furrowed face contracts at the thought of what would happen if she couldn’t receive the money her cousin sends her from Miami every month.

Isabel is just one of the tens of thousands of families that depend on remittances from the Cuban diaspora on the island. Many could not survive only on meager state wages or pensions. Those remittances, the main unofficial foreign exchange inflow into Cuba, are also in the Trump administration’s sights.

It’s her first cousin, also retired and an octogenarian, who sends her the money from Miami through Western Union. A hundred dollars “and sometimes a few more pesitos” mean for her the possibility of buying food that she could not afford if her only income was her state pension, which doesn’t reach 300 Cuban pesos (about 12 dollars).

“When the Revolution triumphed, he got excited and left. Of the family only the two of us are left, we grew up together. He tells me to indulge and I buy grapes, but especially milk,” says the woman. A liter of milk in Cuba costs two dollars, and the state only subsidizes milk for children until they turn seven.

Isabel’s relative says he doesn’t believe the U.S. government will eliminate the remittances, but she’s worried it will. “That man has no feelings and wants to do away with everything. Politics is a very dirty thing. What an ambition…,” the woman sighs as she nervously moves her interlaced fingers on her lap.

The Havana Consulting analysis group, based in the United States, estimated the remittances sent to Cuba in cash in 2018 at 6.6 million dollars, with an average monthly amount of 180 to 220 dollars.

“We are forced to help because the situation is disastrous”

Like Isabel’s cousin, Ernesto Pérez, a 40-year-old Amazon delivery man, doesn’t miss going to the remittance house every month to send money to his two daughters in Cuba. “That I know of, it’s still possible to send through Western Union, nothing has changed with the coronavirus,” he explains.

“The worst thing is the line my daughters’ grandparents have to stand in in Cuba to collect the money; they may be in a line for hours, but in the end they get it. Last month they received 50 CUC (Cuban official currency equivalent to the dollar), but for this I had to deposit 61.50 dollars in Western Union,” he says.

“The situation there continues being disastrous and from here we are forced to help our relatives, not only with money, but also, sometimes, with food and other necessary things,” said Pérez.

This emigrant sends an average of about 100 dollars a month, although this year he also sent his family the necessary amount to buy a 600-dollar refrigerator. Many people on the island depend on dollars from abroad to buy household appliances, among other products.

The multinational isn’t the only way to send foreign currency to the other shore. Pérez explained that he also operates a “direct route” through people who live in Miami, receive the dollars in hand and have mechanisms for the money to “materialize” on the island in CUC.

According to unofficial sources, fear that U.S. government sanctions would force the closure of Western Union in Cuba while the island’s borders continue closed due to the coronavirus, has caused Cuban-Americans to send their loved ones more money than usual in recent months.

“That Cuba is no longer our Cuba”

Gustavo de los Reyes, 74, a retired businessman, recalls with nostalgia: “Cuba was very nice, it was a kind of paradise.” Shortly after the Revolution triumphed, in August 1959, he fled to the United States with his family because his father was imprisoned. At that moment he was 14.

Six decades later, he has lost hope and the desire to return to his native country. His case illustrates that of the many Cubans (now elderly) who left to never return, or at least not while the Revolution is still in power.

“I’ve always wanted to go back and go with my daughter to show her our Cuba, but it’s very sad to go now, a sacrifice. That Cuba is no longer our Cuba,” he regrets.

Gustavo affirms that “in the 1950s the Cuban middle class reached an incredible level compared to the rest of Latin America in general and to Europe, including Spain”, but “all of that was lost.”

After completing his studies in the U.S., he started business in the livestock industry in Venezuela, where he married twice and had a daughter. However, in more recent times he was forced to flee the country, which is why he considers himself a double victim of socialism. “The Cubans came to Venezuela, (Hugo) Chávez fell in love and became controlled by Fidel Castro. He made Venezuela a colony of Cuba and (Nicolás) Maduro was trained for the same thing.”

Gustavo is very critical of the Obama administration’s opening policy, considering that “there was a certain economic encouragement, but quickly everything went for the Castros and not for the people.” That is why he is a follower of the hard line of Donald Trump, who ended his predecessor’s thaw, strengthened the embargo and imposed new sanctions on Cuba.

“It’s important to control the outflow of money, millions of dollars that are used to support the Castros. Now that Venezuela can no longer give them anything, they count on remittances from Cuban families and that is a very serious problem,” he says.

Even so, Trump’s pressure seems insufficient: “We are keeping Cuba alive under Castro’s authoritarianism,” he protests.

“I’m not going to depend on the president of another country and even less of the United States”

Nelson Rodríguez, 40, a businessman, was one of the many Cubans who, after years of working abroad, returned to the island to open a business in the heat of the thaw. He opened El Cafe in the neighborhood of Old Havana in 2016.

“It was totally crazy. We started empty in April and in August we already had an incredible number of customers,” he says.

Famous for its sumptuous breakfasts, this café received every day with brunch dozens of American tourists who recovered their energy after walking through the historic center all morning. The arrival of Donald Trump in 2017 and his administration’s progressive sanctions on Cuba, including the restriction of entry of travelers and the prohibition of cruise trips, were a blow to his business.

“A decline in American customers was felt and has continued so far. Every year we see that less and less are coming.” Nelson has just reopened his café after the COVID-19 stoppage and little by little it’s filling up with Cubans and foreigners residing in Cuba.

When tourism returns to Havana, he hopes to attract more Europeans to make up for the almost total absence of the once ubiquitous Americans. Other Cuban entrepreneurs are confident that the situation will improve if Trump loses the presidential elections in November. Nelson isn’t. “No matter who wins, I’m not going to depend on the president of another country and even less of the United States.”

Text and interviews by Jorge Alberto Pérez Domingo in Miami and Atahualpa Amerise in Havana, for EFE.

EFE/OnCuba