There is a perception that the Helms-Burton Act, whose full application was activated months ago by the Donald Trump government, concerns only real estate or businesses nationalized in Cuba at the beginning of the Cuban Revolution. Nothing further from reality.

The law barely makes two exceptions: property currently occupied as family residences or in the hands of a diplomatic mission cannot be claimed. But nothing more, because the law, except for these two cases, does not specify anything else or makes a precise definition of the concept of ownership. It barely says that a property subject to compensation claim had to be worth 50,000 dollars or more at the time of nationalization.

This opens the possibility to many interpretations because “property” is all that belonged to someone and on the Caribbean island in the early 1960s the State nationalized a series of properties that are not necessarily real estate. Also objects such as works of art, for example. Some of which are part of several art museums’ collections.

After the application of Title III of the law was unfrozen by the Trump administration, doubts about what would happen to the works of art, paintings, sculptures, objects or engravings by important world authors that wealthy families left behind when they left the country after the Revolution started circulating very discreetly in the social networks of the cultural sphere.

It is an intricate discussion that still remains behind the scenes because, among other reasons, the issue of claims for the confiscation of real estate has taken the lead and the issue of the rest has lagged behind.

However, it is something that has started surfacing very discreetly, and few want to comment publicly as OnCuba has confirmed in the last two weeks.

“Actually it hadn’t occurred to me but it is a possibility. Art is not beyond this American law,” a Spanish dealer who works at a multinational auction house told OnCuba. The problem, he emphasizes, is that it will be “very difficult” to make a country like Cuba agree to hand over works only by the decision of a foreign court.

Both this dealer and other analysts, who closely follow the twists and turns of the saga of claims of nationalized properties, point out that in the Cuban case of properties, contrary to what happened in European countries after the German occupation during War World II, where museums such as the Louvre and private collections were sacked by the occupation troops, on the island they were simply abandoned by their owners.

This makes a difference between the two cases. In the first place because the Western powers did not recognize the Nazi government that practiced that looting of works of art. In the case of Cuba, it is very different.

According to a study presented by Mari-Claudia Jiménez a decade ago at a conference of the Cuban Association of Economists, the legal framework is what defines everything. Take, for example, the case of the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union when the communist governments disappeared.

“The change of regime is a key requirement for a possible restitution of cultural heritage in Cuba’s case. And that is why the restitution of art confiscated by the Nazis is dealt with in a different way to works of art nationalized by communist regimes,” the study indicates.

Cuba considers all the works of art that were in the country in 1959 as part of national heritage, which completely changed the legal regimen of those works’ ownership. The same happened in the former Soviet Union after the 1917 revolution, explains the author.

“What can Cubans do if they find a work of art that belonged to them in Cuba? Can they sue the current owner to return it? Again, here the key in relation to Cuba is that there has not been a (political) regime change, therefore the options are limited. If this work is found in the United States, the chances of winning a lawsuit against the current owner are questionable because, in the current situation…the U.S. government officially recognizes the Cuban. As a result, any expropriation of property or nationalization against its own citizens may be official acts of State which, taking into account the concept of individual sovereignty, foreign courts do not usually treat as a case,” the study by Jiménez underlines.

In October 1962, when nationalizations took place in Cuba, the U.S. government accepted them as a fact precisely protected under the doctrine of the State Act. In a speech before a group of businessmen, Secretary of State Dean Rusk stressed that all sovereign states have the right to expropriate property, regardless of whether the owners are nationals or foreigners, but…the owner must be adequately compensated for his property.

So far there is only one example of a work of art confiscated in Cuba and later recovered by its owners. According to an article in the magazine The Art Newspaper, the emblematic case is that of the Fanjul family, but it was possible because the painting they recovered was outside of Cuba.

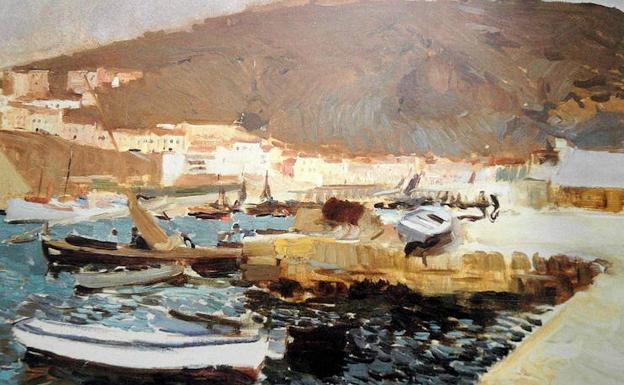

It happened in 2005 when the Fanjul family, large sugar industrialists in Cuba who lived in what is now the Museum of Decorative Arts in Havana, managed to get a painting by the Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla called Vista de Málaga returned, although initially the work was not identified.

It all started when the Sotheby’s auction house in London asked a great-granddaughter of the Fanjul-Gómez Mena family to identify a painting that was going to be auctioned. Alerted, the family began the efforts to recover it. They succeeded, following an agreement that remains confidential until now but which was an outcome that is very rare and difficult to repeat.

In fact, the Fanjuls are aware of that. They are not opposed to their works being exhibited publicly, they said it during the Vista de Málaga case. What they aspire to is compensation because they have changed hands against their will.

So far no lawsuit related to the Helms-Burton has to do with works of art. It doesn’t mean they won’t try. But the most difficult part, specialists point out, is to get a court in the United States to define exactly what a property is in light of this law and if it has legal right to claim an artistic property in the hands of the Cuban State.